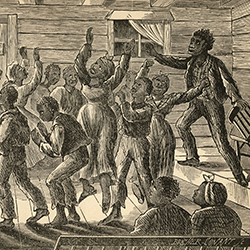

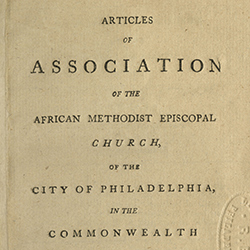

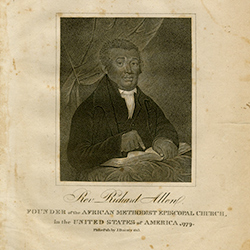

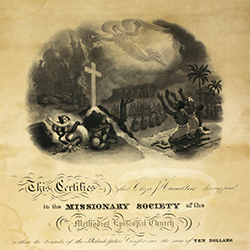

In the Americas, people of African descent have had to adapt, accept, resist, and create religious practices because of the nature of their forced migration and coerced religious conversions. In spite of the disruptions that the slave trade, slave sales, fugitive state, and even freedom wrought on their lives, their faith endured. The religious practices of African Americans also ensured the survival of their various cultural practices and allowed space for the creation of new ones. By the 1700s, African Americans began to found Christian churches, to reinterpret the Bible to emphasize how enslaved peoples fled bondage in Egypt, and to create a liberation theology that centered Africa. Like the ancient psalmist proclaiming “Princes shall come out of Egypt; Ethiopia shall soon stretch out her hands unto God,” African Americans saw themselves as a chosen people for whom freedom would be gained by a reliance upon their faith and good works.