How We Paid Ourselves

Throughout the 19th and 20th century, there were prosperous Black businesses. These businesses often provided opportunities for activism. During the Great Migrations, millions of African Americans migrated from the South to Northern cities such as Philadelphia and Pittsburg. They did so to escape Southern white violence, earn a living wage, and find better employment opportunities. Despite many obstacles these business owners faced, some Black businesses thrived, enriched their local economy, and inspired the pursuit of education and entrepreneurship.

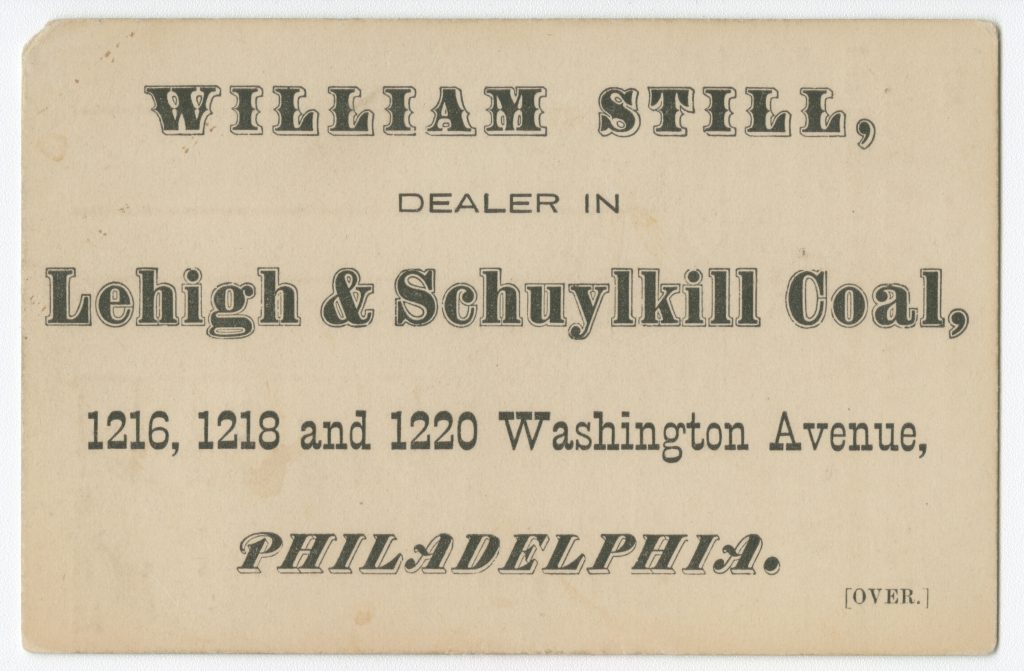

William Still, dealer in Lehigh & Schuylkill Coal, 1216, 1218 and 1220 Washington Avenue, Philadelphia ([Philadelphia, 1875]). Lithograph.

LCP P.9939

William Still is mostly known for being a prominent abolitionist and his involvement with the Underground Railroad. However, he was also a successful businessman in Philadelphia. His businesses provided him the opportunity for activism and funding for his book, The Underground Railroad, which provides intimate details from formerly enslaved Africans who escaped slavery with the hopes of reconnecting lost families. Here is a business card advertising his coal business.

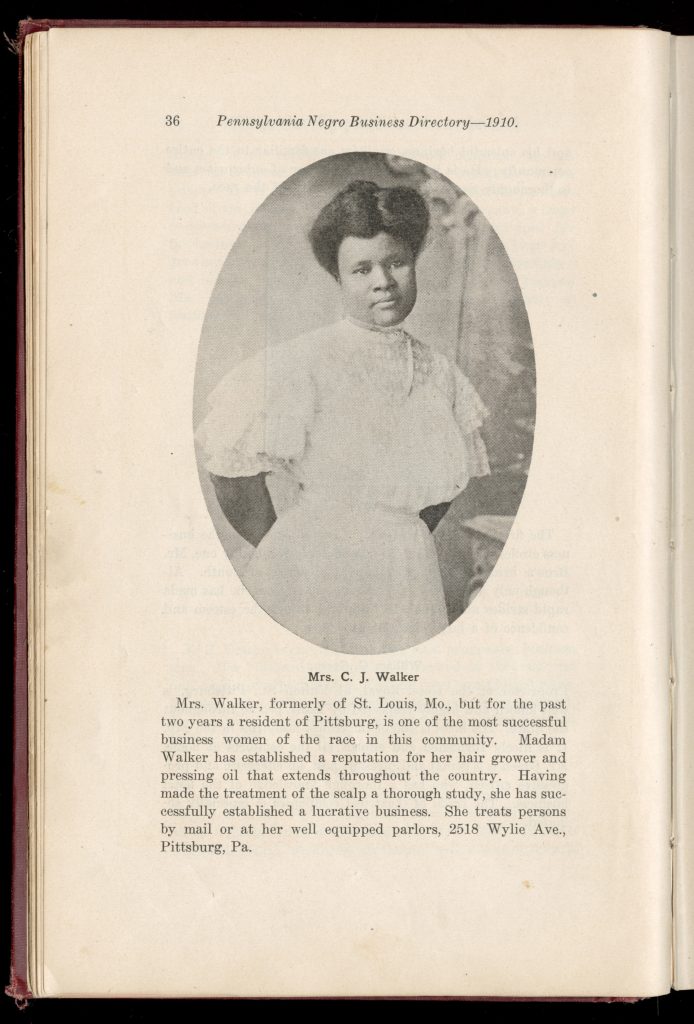

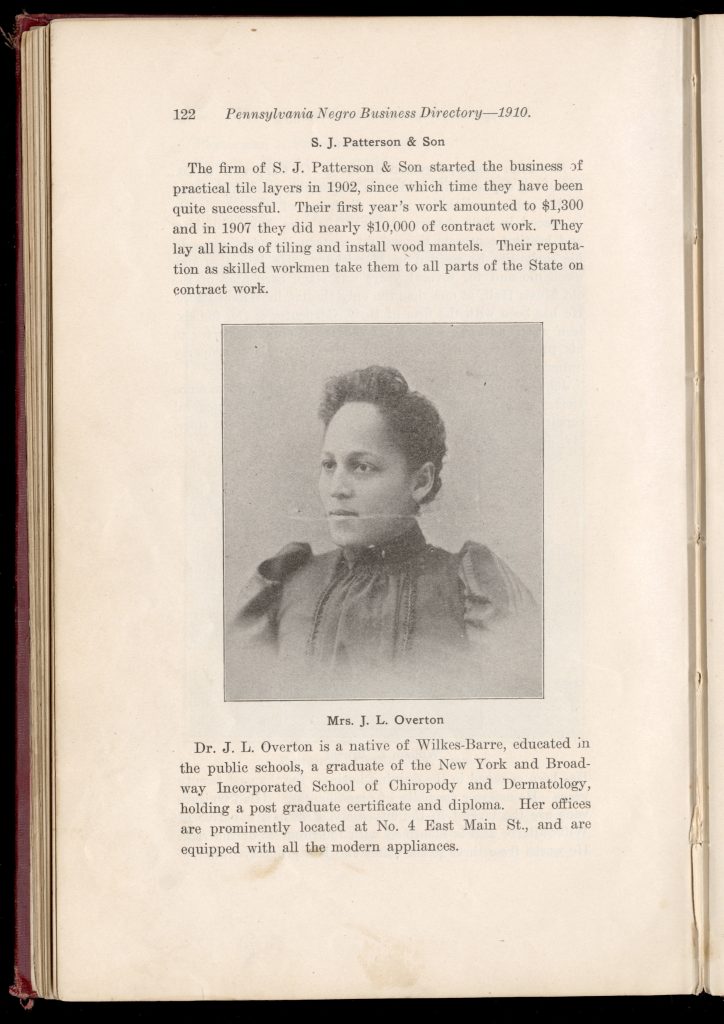

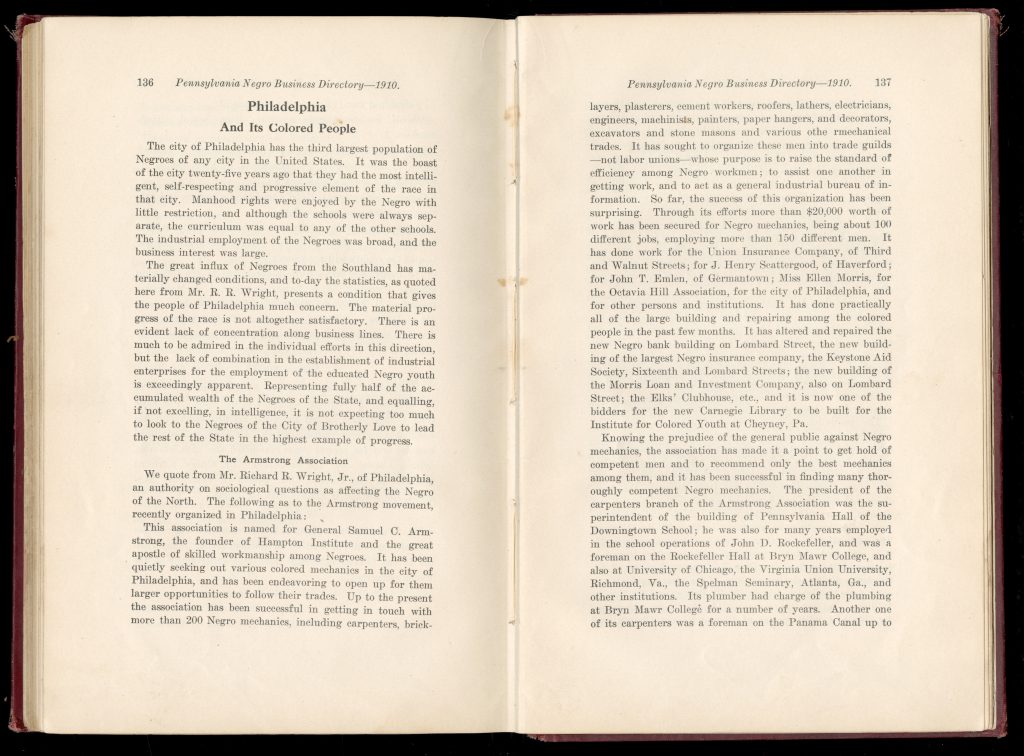

Pennsylvania Negro Business Directory, 1910 : Industrial and Material Growth of the Negros of Pennsylvania (Harrisburg, 1910). Gift of Donald H. Cresswell.

LCP 78958.O

Pennsylvania provided the Black community with greater privileges and opportunities than they could find in other states. The Black entrepreneurs in Pennsylvania created and provided goods, services, and support that Black consumers could not find elsewhere. While some white business men catered to Black trade, they denied them employment. This realization prompted them to open up their own businesses. This book includes advertisements as well as brief descriptions for successful Black businesses.

Madam C. J. Walker was an entrepreneur, who created a natural hair care line for African American women. Originally from St. Louis, she later moved to Pittsburgh because of its thriving Black business community. Within two years, she became one of Pittsburgh’s most popular business owners and eventually the richest African American woman in the United States. This success allowed her to become an activist and philanthropist.

The Walker System consisted of a pomade for scalp improvement, pressing oils, and hot combs. She differentiated her brand from white businesses that manufactured Black hair care products through her personal connection to hair loss. Before she implemented mail-orders and grew her chain of parlors, she employed Black “beauty culturalist” saleswomen to market her products in the Black community.

Jerusha Louise Overton was another successful Black business owner from Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Dr. J. L. Overton was a graduate of the New York Broadway Incorporated School of Chiropody and Dermatology with a postgraduate certificate diploma. She had a strong interest in promoting race interests and enterprises within the community.

In 1910, less than 2% of Wilkes-Barre’s population were people of color. She practiced as a chiropodist and dermatologist in offices which were equipped with modern appliances throughout Wilkes-Barre. Dr. J. L. Overton was probably the only chiropodist there with high rank.

The Armstrong Association, made up of an interracial board and named after General Samuel C. Armstrong, created jobs for African Americans in mechanical careers. These positions included carpenters, bricklayers, plasterers, cement workers, roofers, latherers, electricians, engineers, painters, and other mechanical trades. The association raised more than $20,000 for Philadelphia African American businesses. 150 African American men benefited from this opportunity.

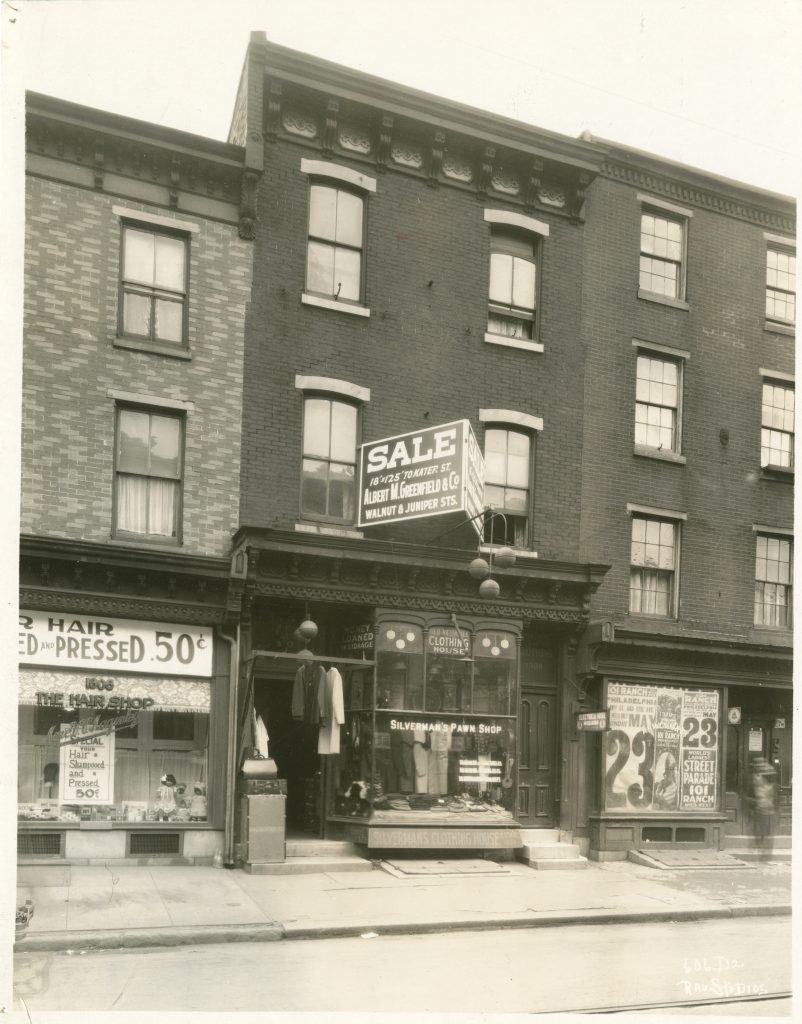

Rau Studios, 1908 South Street (Philadelphia, 1927). Gelatin silver.

P.9789.13

This real estate photograph depicts several buildings, including an African American parlor named “Hair Shop of Mme. V.V. Maginley,” located on 1906 South Street. The hair shop displays beauty products, black dolls, and a sign that states “Special: Your Hair Shampooed and Pressed 50 cent.” According to The Negro in Business in Philadelphia, there were 25 hair culturist and 66 barbershops in Philadelphia in 1917.

This business was located in Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward. The Seventh Ward served as a point of entry for Southern Blacks during the Great Migration and spanned from Spruce to South Street and from Seventh to Nineteenth Street.

G. Mark Wilson, Antique store, Pine Street e. of 13th St. ([Philadelphia, 1923]). Gelatin silver.

LCP P.8513.175

In the 1920s, African American James Eham owned an antique shop in the Seventh Ward on 1237 Pine Street in Philadelphia. Eham was formerly enslaved in Virginia as a young boy and later moved to Philadelphia as a freed man to work at the Centennial International Exhibition in 1876. Before becoming a business man, he worked as a waiter making three dollars a week. By 86 years old, he owned two shops in Philadelphia and one in New York and served elite wealthy patrons such as the Pennsylvania Governor.

His shop had grandfathers’ clocks, old engravings and pictures, old coins, bric-a-brac and books. The exterior of this two-and-a-half story business was decorated with antiques and curiosities.

Photographer’s manuscript note on verso: “An interesting old negro is the proprietor of this curious shop.”