African Americans and Lost History

Unidentifiable people are pervasive in historical photographs. Men at work, people in crowds, children on street corners, all represent the nameless faces that populate our historical record. Unless the photographer or owner of the photos thought to record the names of the subjects in them, the identities of the faces are often lost to time. And sometimes, even when names are given, we still do not know who people are.

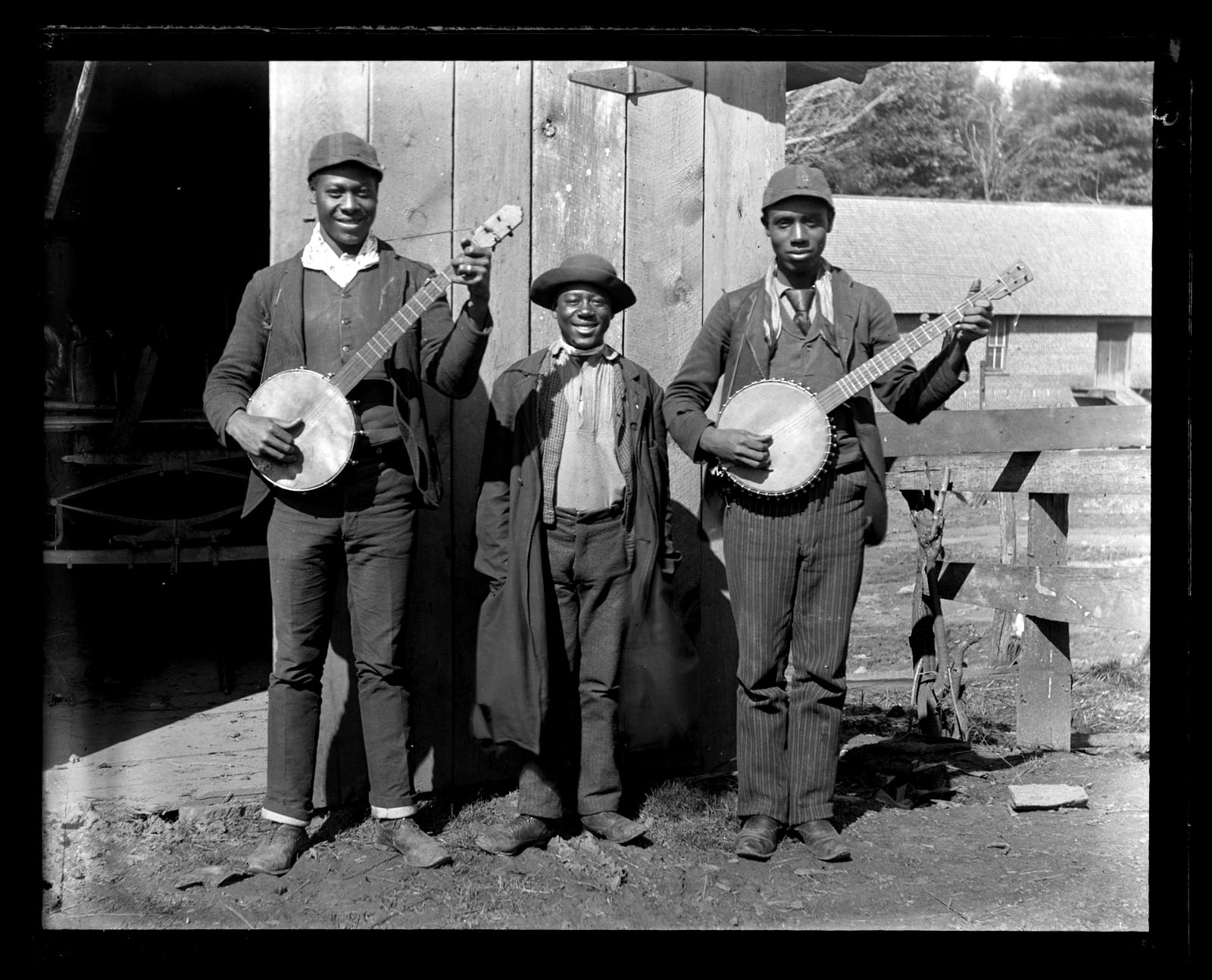

While doing historical research for the Marriott C. Morris Collection, I was particularly intrigued by four African Americans who posed for portraits. Throughout this collection, only twenty-one images of African Americans exist. The vast majority of these images come from a ceremony at the Hampton Institute, a historically black college in Virginia. Other images capture African Americans in daily life. There are quarry workers in Bermuda, groups of children and young men, and a festival image. Most of these unnamed individuals are entirely unidentifiable, but I wanted to see if I could provide some history to the people Morris chose to document.

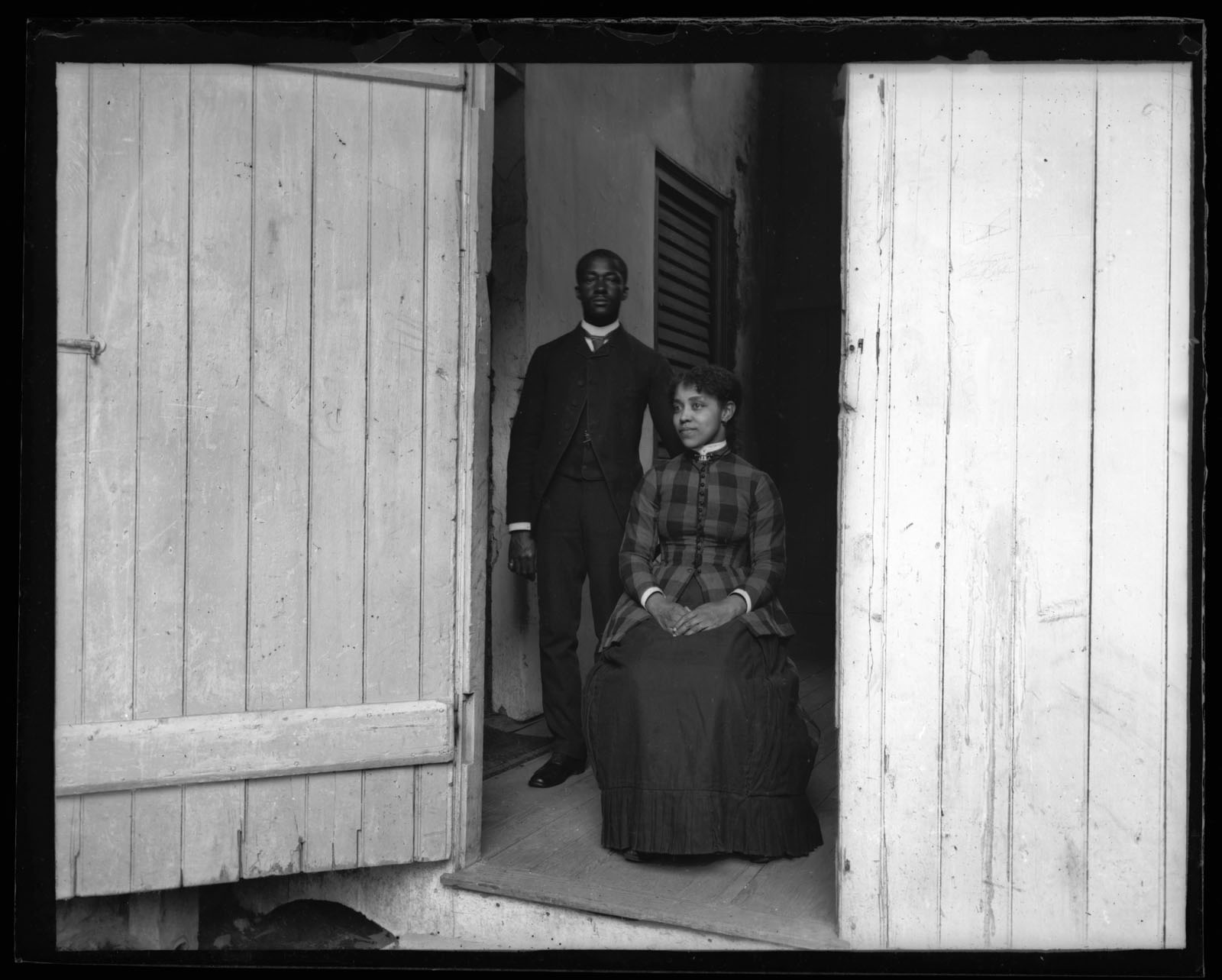

The first is a negative of David Murray and his wife, dated May 15, 1885. According to the caption provided by Morris, David Murray worked as a waiter at Morris’s alma mater Haverford College. This is about the extent of the information we have on Murray. After extensive searching, I could not positively identify who the Murrays were. Some questions I wish I could answer include: Did Murray work there for long? How long were he and his wife married? How old were they when this picture was taken? From the negative we have we can only tell that the Murrays were fairly young and that David Murray worked at a Quaker college. Other than this, we don’t know a lot about this couple. Unfortunately, the mystery must remain for the time being.

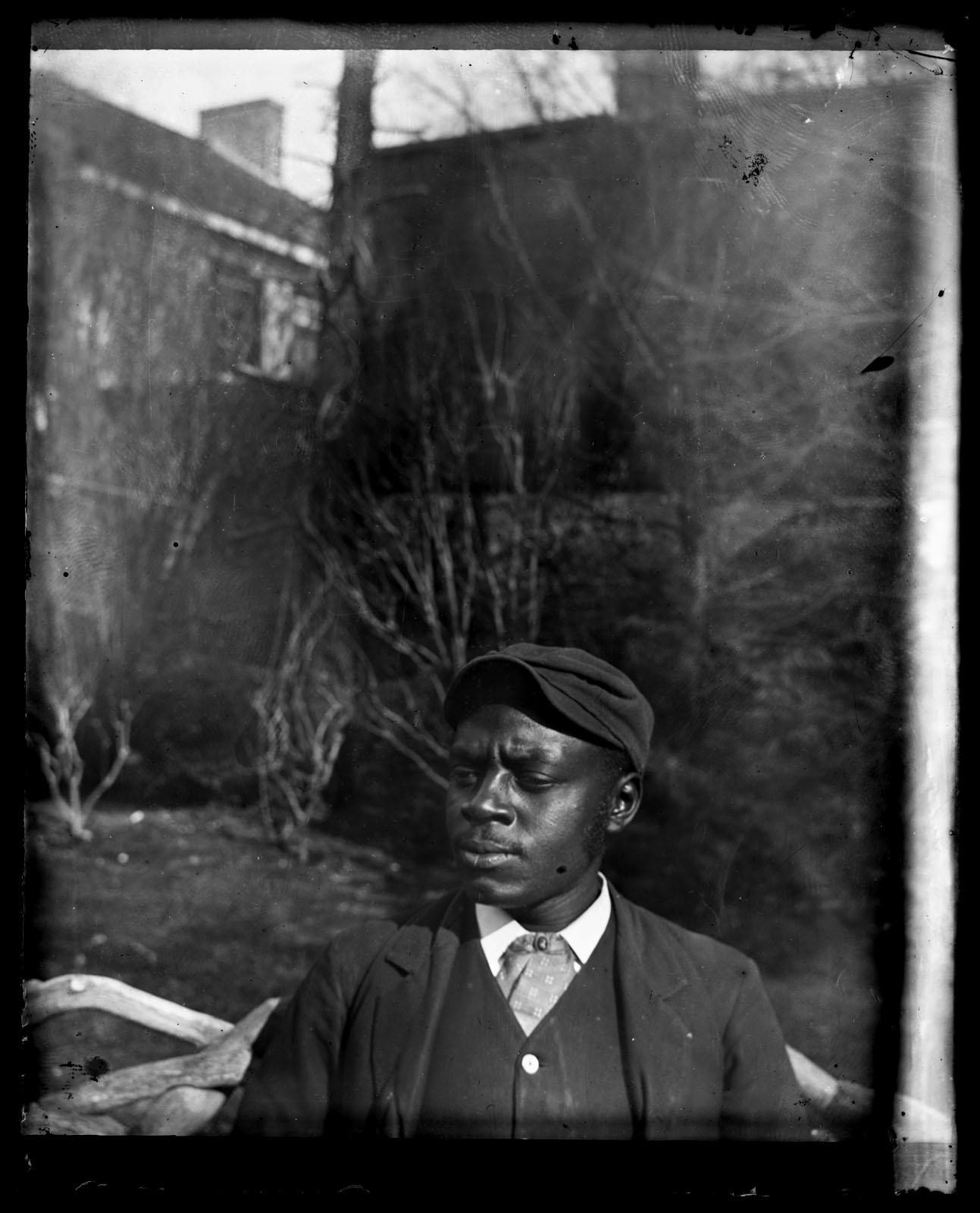

Another mysterious figure is James Rodgers, seen in this negative. Taken circa 1885, this negative provided no other clues as to the identity of Rodgers. The two portraits Morris took, one full- and one half-length, show some sort of residences in the background. It is likely that they were taken in Philadelphia where Morris lived, but I cannot positively confirm that. Working under this assumption, I tried to find a James Rodgers who may fit, but unfortunately the name is too common. While a few candidates seemed promising, I could find no other information that would positively link one of them to our Rodgers. The negatives we have show Rodgers as a well-dressed younger man, possibly in his 20s to 30s. Without other context clues, we cannot say how old he was, what his occupation was, where he lived, or whether he was married or not. For now, all we have is his name and face.

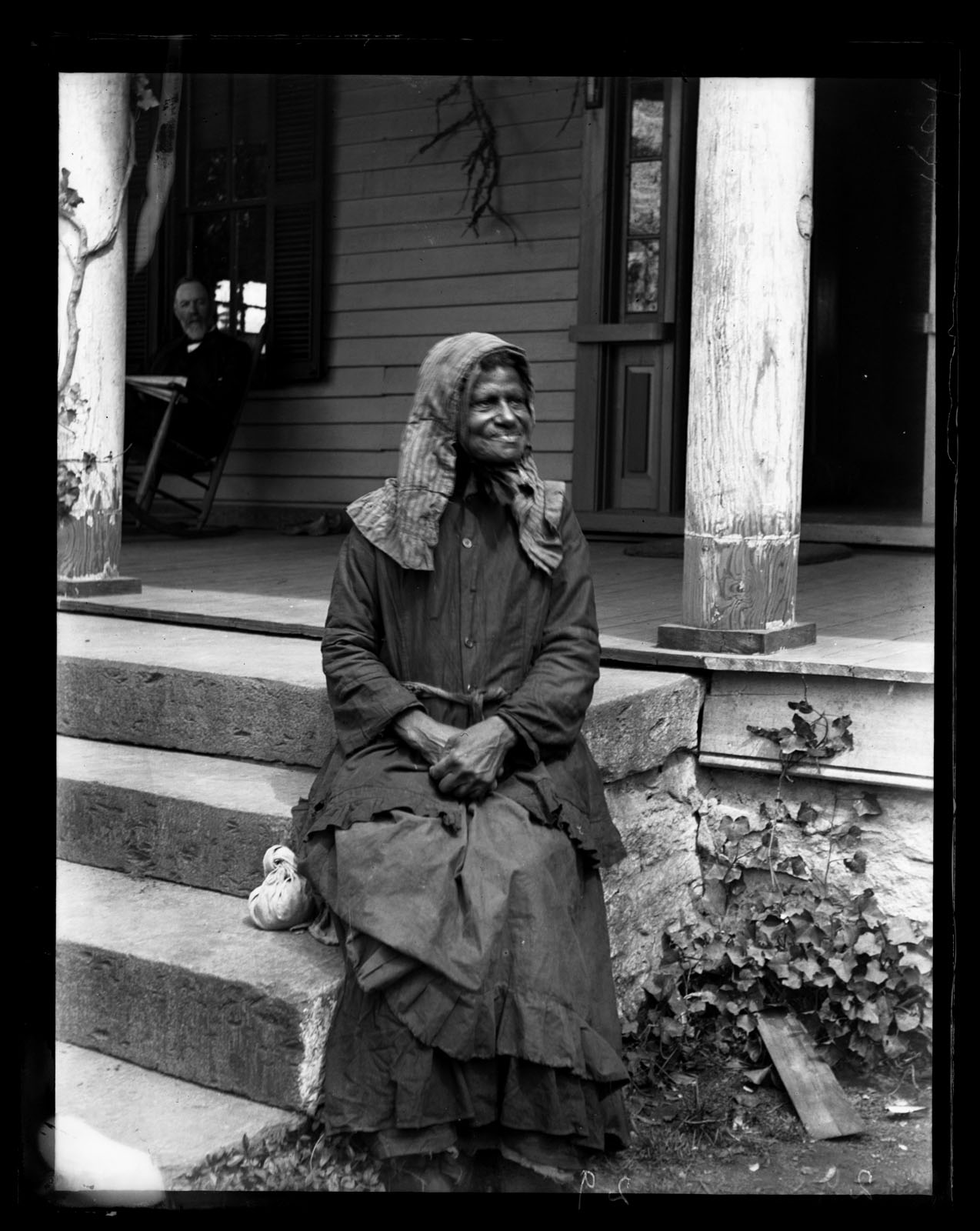

The final person I attempted to identify was Aunt Phebe as seen in this negative. Taken at Mcaboy House, a hotel in Polk County, North Carolina, this negative shows an elderly African American woman sitting on the porch steps. We are given no other clues as to her identity. Digging into my research, I was delighted to find a reference to an Aunt Phoebe, an “oldtime” African American woman married to Uncle Pauldo in a 1978 North Carolina magazine. Uncle Pauldo worked at Columbus Mills plantation, the precursor to the Mcaboy House hotel. Unfortunately, any additional information about these two that may have been in the magazine is locked under copyright protection. Still, with this small glimmer of information, I was able to find census records for Phoebe Mills, born circa 1806 and married to Pauldo Mills, born circa 1802-1806. His occupation was listed as “farmer” in both an 1880 and 1870 census. I also found two marriage certificates for a Poldo Mills and Pheba Turner, dated January 22, 1872, which seem to contradict the 1870 census, which listed them as already married. The two could have lied to the 1870 census taker, but I cannot be sure. The 1870 census also lists Sarah Mills, a twenty-year-old member of the household (Daughter? Niece? Unrelated?). Compared to the other two portrait sitters, I now had a bounty of information for Aunt Phebe. I can fairly confidently say that this negative depicts Phoebe Mills, born circa 1806 and married to Pauldo Mills, a farmer from the Columbus Mills plantation. A very exciting find.

African Americans are often overlooked in our historical narratives. I wanted to try to add context to these images precisely because of the gaps in historical records of African Americans. While I struck out twice, I am happy to be able to add Phoebe Mill’s information to these records. With more in-depth research of sources at Haverford College, David Murray and his wife may also be identifiable, and maybe someday a researcher will recognize the buildings James Rodgers stands in front of to give us a place to start researching. As for the rest of our anonymous images of African Americans, we will probably never know their stories. At the very least, we do have these images to expand our perceptions of historical America.

Em Ricciardi, Curatorial and Reading Room Assistant