Cataloger’s Amusements: Pope Joan

Cataloger’s Amusements: Pope Joan

Louis the Pious

Sergius Secundus, Leo Quartus, and Joannes Septimus (Pope Joan)

The Nuremberg Chronicle, more properly Liber Chronicarum, was commissioned by two Nuremberg merchants, Sebald Schreyer and Sebastian Kammermeister. It’s a biblical paraphrase and history of the world written by Hartmann Schedel, who worked from his extensive personal library of manuscripts and printed books. The Latin edition appeared in July 1493, followed by a German translation at Christmas the same year. The woodcut illustrations were designed and executed in the workshop of Michael Wolgemut, the same workshop where Albrecht Dürer apprenticed, and I find them particularly appealing to my 21st-century eye.

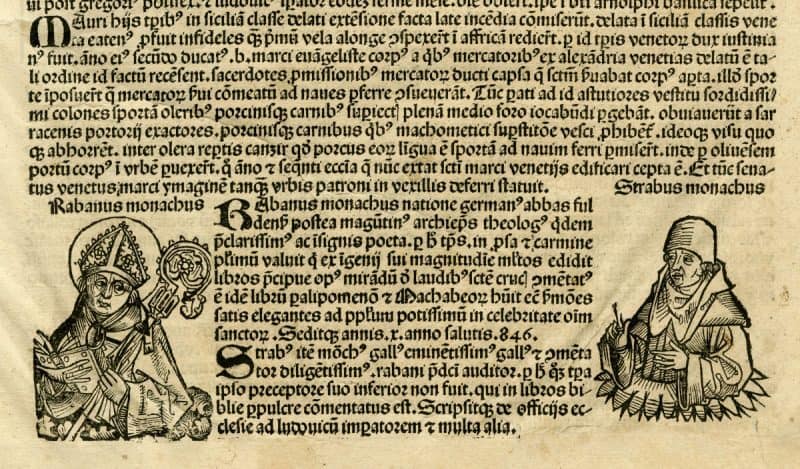

The front of the leaf recounts 9th-century European history and is illustrated by portraits of some important figures. At the top of the page, there’s Louis the Pious, King of Aquitaine, son of Charlemagne and Hildegard, also known as Louis the Debonaire. Notice his turned-out foot. In the lower left corner we find Rabannus, a Benedictine monk and Archbishop of Mainz, an important writer and teacher of the Carolingian era, looking properly clerical. In the lower right we have Walahfrid Strabo, “Walahfrid the Squinter,” theologian, writer, and tutor to the son of Louis the Pious.

Rabannus and Walahfrid Strabo

On the back we find the papal history accompanied by portraits of 9th-century popes: Sergius Secundus (Pope Sergius II, who ruled 844-847); Leo Quartus (St. Leo IV, 847-855); and Joannes Septimus? Never mind that Pope John VII (705-707) is from the previous century and we should be up to John VIII by then, or that Pope Benedict III (855-858) follows St. Leo IV in the modern papal lineage. Ignoring for the moment the papal tiara, “Joannes Septimus” sure looks like a Madonna cradling a child. Oh my goodness, we’ve got Pope Joan!

Joan, a scholarly woman who disguised herself as a man, is said to have risen through the ranks of the church to be elected Pope and rule from 855 to 857. She could hide a lot of things under her voluminous robes including a pregnancy, but when her water broke during a papal procession she was found out. She died shortly after giving birth, either by natural causes or by the hand of man. So goes the story.

Pope Joan

The account of Pope Joan first arose in the 13th century and spread across Europe in oral and written form. It appears in at least two 13th-century chronicles, one by Jean de Mailly and another by Martin of Opava. Hartmann Schedel must have been aware of those works, and it’s important to remember that he was researching a scholarly history and not writing fiction.

The legend of the female pope was declared untrue in 1601 by Pope Clement VIII. In many copies of the Nuremberg Chronicle, Pope Joan’s image is crossed out or excised entirely, and the page is annotated denying the legend. And yet our leaf survived, separated from its original binding but otherwise mostly unharmed. Who rescued our Joan? We know where she’s been for the past dozen years or so, but where did she hide for the 400 years before that?

Rest easy, Joan, you’re safe with us.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!