See America First with Janet Morris

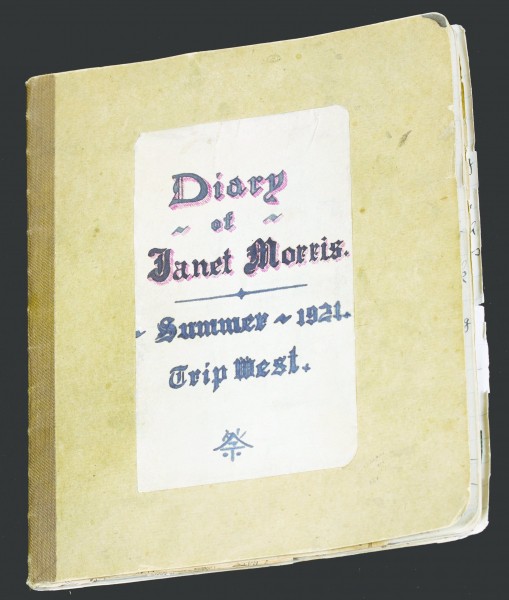

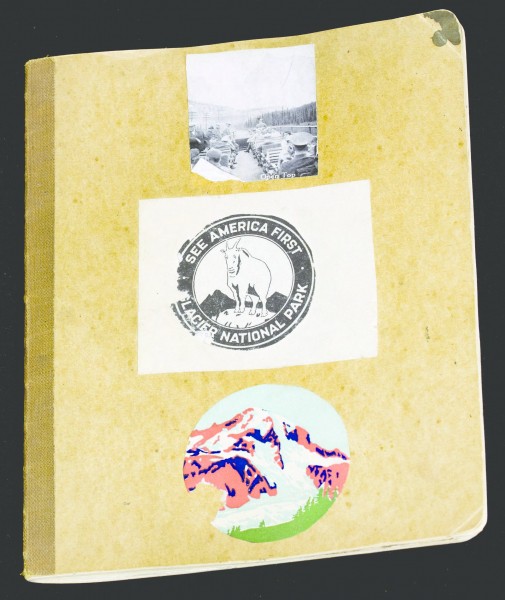

During my six-week summer internship at the Library Company of Philadelphia, I have had the pleasure of immersing myself in the Library Company’s album collection in the Print Department. Throughout all of my work on various stimulating projects at the Library Company, my mind has continually circled back to one item in the album collection: the diary of Janet Morris chronicling her family trip west in 1921. The two volumes trace the Morris family’s journey from Philadelphia through the northwestern United States and Canada in July and August of 1921. The diaries contain Janet’s daily observations as well as sketches, lists, and clippings from publications about the sites she sees. Along the way, the family visits everywhere from big cities to backwoods trails to national parks. The diary struck a chord in me from the instant I saw the cover of Janet’s notebook decorated with stickers depicting mountains and advertising Glacier National Park. After some quick calculations, I was delighted to discover that Janet was fourteen when she made this trip west. I too was around fourteen when I traveled to the western national parks with my family, and I too kept a diary-like scrapbook.

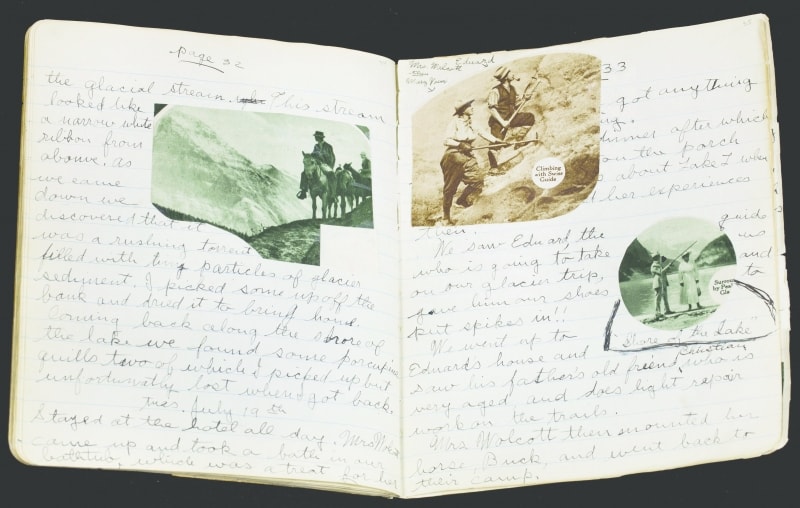

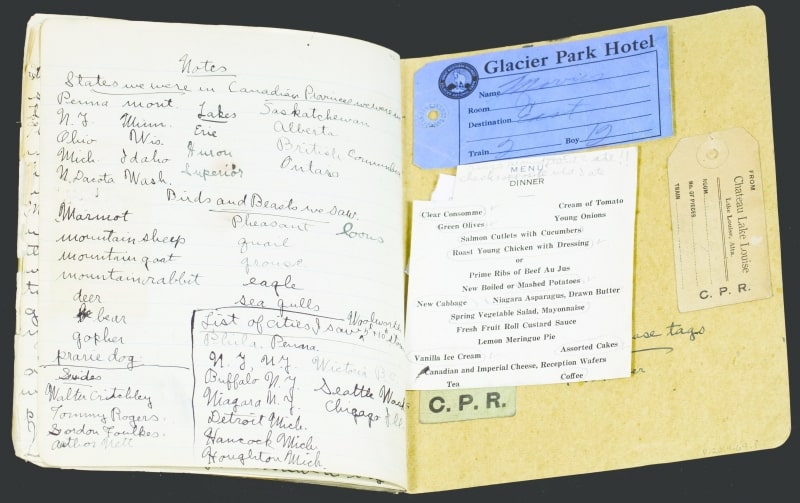

Janet Morris labels the first volume as a diary in her own hand-lettering, but the Print Department labels it a scrapbook. The diary certainly resembles a scrapbook. The notebooks are included in the album collection because the ephemera that accompanies the personal narrative makes the diaries a visual and tactile feast. The line between diaries and scrapbooks is blurry because so many scrapbooks contain some form of written narrative to give context to the “scraps” and so many diaries include material elements. However, not everyone uses the term “scrapbook” so forgivingly. In the late nineteenth century, scrapbooks were heavily commercialized and marketed as orderly creative outlets. Self-proclaimed scrapbook connoisseurs published how-to guides instructing people on the proper use for a scrapbook and the most aesthetic way to arrange its contents. Scrapbooking was formulaic, and scrapbooks from this time are incredibly tidy, with items organized by color, date, or function and laid side-by-side at right angles. Even today there are scrapbooking kits and books that provide a similar structure. In contrast, Janet’s notebooks show a modern and youthful sensibility. Instead of the for-show perfection of scrapbooks, Janet’s diary is an unflinchingly personal account (in one entry she remarks, “One of my infernal boils started again.”) It is a record for herself, and the scraps she includes are to enhance her own memories. It is not for public consumption, unlike scrapbooks filled with family photographs or impressive postcards that were meant to sit on parlor tables and draw the attention of guests.

The diary reads almost like a novel, with humorous asides, breathtaking scenic descriptions, and defined characters. There is Janet’s germaphobe mother who is constantly complaining for want of a “nice clean place” to eat or rest, and there is Janet’s intelligent father who always stops to document the trip in photographs (many of which are included in the Library Company’s Marriott C. Morris collection.) There is dramatic Aunt Elizabeth who dotes on Janet but is forever falling ill at the most inconvenient times. And there are Janet’s brothers, suave Marriott who seems to meet a new girl in every state and Elliston, who follows in Marriott’s footsteps.

Janet notes several times that she, her mother, and her aunt set aside dedicated time to write in their diaries. Whenever her father and brothers take photographs, Janet and the women use the opportunity to update their diaries. Her diary is shockingly consistent for that of a teenager. Entries of a similar length appear every day, along with meticulous lists written in the back of the notebook for subjects such as “Birds and Beasts we saw” and, my personal favorite, “List of cities I saw Woolworth 5¢ & 10¢ stores in.” Her penchant for diary-keeping and scrap collecting would continue into her young adulthood (as has mine). She kept similar scrapbook-like diaries during her trips to Europe in 1925 and 1931, both of which are also in the Print Department’s collection.

Many of the habits of scrapbooking and diary-keeping that Janet practices are still in use today. I know this not through research, but because at age fourteen I employed the same techniques. Janet does not include any of her own family photographs but rather clips pictures from advertisements and brochures for landmarks, hotels, and restaurants. On the road, my family was too busy to stop to print photos, so I pasted glossy brochure photographs of smiling families that were not my own standing beneath redwoods or hiking up mountainsides. The technology of photography and the rapid availability of printing have come a long way since 1921, but a young scrapbook artist turns to the same time-honored cutting and pasting today as she did in 1921.

My personal philosophy of scrapbooks at Janet’s age was simply keep everything: every napkin, every ticket stub, every campsite map. Janet shows a more refined taste. She includes only pictures that enhance her narrative. She often annotates by drawing arrows from her text to the photos or, in one case, using an asterisk to form a makeshift footnote. She pastes in the clippings first and then writes around them. It is evident that this is an off-the-cuff account made while on a grand adventure, not a hazy, nostalgic album compiled afterwards with greater physical resources but fewer memories.

Janet Morris was part of a generation (and socioeconomic class) that was one of the first to be exposed to national parks as we know them today. The National Park Service was formally established in 1916, just five years before Janet would visit Glacier and Mount Rainier. The advent of automobiles changed travel and sightseeing for good. Though Janet and her family mainly travel by train and ship, they are shuttled to locations within the parks by bus. The family takes advantage of the luxury hotels and restaurants that were beginning to emerge to accommodate the influx of visitors to the parks, as well as guided camping trips and excursions on horseback marketed towards tourists.

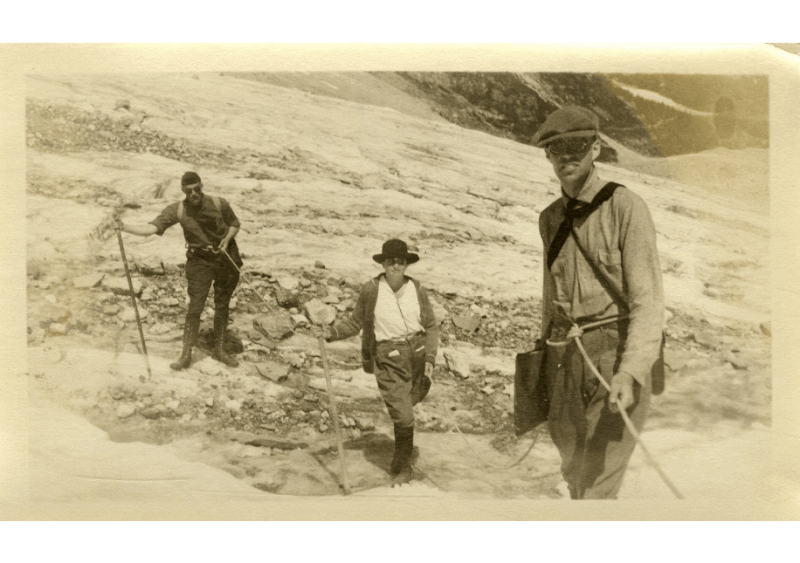

Since long before the formal establishment of the National Park Service, national park areas have been considered historically male environments for traditionally masculine activities like camping, hiking, and all-around “roughing it.” However, Janet engages with the parks as a writer and explorer with a deep, aesthetic appreciation. She rides on horseback for days (in the rain no less), camps in a tent, and scales glaciers—all while wearing pants, I might add, which were still taboo even for most women’s athletic activities at the time. At one stop she remarks, “The lake and the surounding [sic] Mts. are wonderful. The emerald green blending with the ruged [sic], snow capped mts. and the trees with an unsurpassed beauty.” Her diaries give a portal into the mind of a girl exploring, learning, and thriving in places where women were usually discouraged. Her account of her trip is funny, poignant, and still rings true today.

Emma O’Neill-Dietel

LCP Intern

Sources:

Tucker, Susan, Katherine Ott, and Patricia Buckler, eds. The Scrapbook in American Life. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2006.