Annie Besant and the Path to Authorial and Bodily Agency for Women

This summer, Franklin & Marshall intern Lydia Shaw has been working on women’s history projects at the Library Company. With birth control in the news recently, she reflected on sources in the collection that relate to the history of contraception before the development of effective birth control pills in the 20th century. Lydia examined the life and work of the British writer Annie Besant, one of the most vocal advocates for birth control in the 19th century, when even discussing the subject could be judged obscene by the courts.

Annie Wood Besant (1847-1933) writes in her book Marriage: As It Was, As It Is, and As It Should Be that “[t]he world is very young, and has only just begun to cast off injustice” (5). Besant is known for her advocacy in women’s rights, marriage reform, family planning, labor reform, and Indian Nationalism. Besant was born in London. After her father and brother died when she was still a child, she was sent to live in Harrow with a family friend, Ellen Marryat, who ran a school for impoverished children. Besant later married clergyman Frank Besant in 1867, after a fourteen months’ engagement, during which she deliberated the pros and cons of marriage.

Besant was politicized by her first marriage, during which she experienced firsthand the systemic sexism marriage upheld. Besant, who had familial connections within the literary sphere, published her first work during her marriage to Frank Besant and was deeply frustrated when the money she earned was legally claimed by her husband. Despite her inability to claim a profit due to laws forbidding women to own property, she continued to publish short stories and other works during her marriage. However, after giving birth to two children in 1869 and 1870, Besant grew more cognizant of the domestic role expected of wives, and she lost the ability to pursue writing. She and Frank Besant divorced in 1873, when Besant’s views became more radical and she condemned established religion.

After her divorce, Besant moved back to London and resumed writing, though this time she published political works. She became active in political societies in London, including the Nationalist Secular Society, the Fabian Society, and the Malthusian League. She wrote political weekly columns for the National Reformer and gave her first lecture in 1874 on marriage reform, family planning, and women’s rights.

Besant’s advocacy in marriage reform stemmed from living through a marriage in which she was deprived of agency over her body and actions. In her book Marriage: As It Was, As It Is, and As It Should Be: A Plea for Reform (1878), Besant challenges this long-perpetuated system of marriage. She argues that it negates women’s legal rights, limits women’s personal liberties, and effectively strips women of all social power by denying them property. Besant suggests means for reform through tangible action: passing an Act of Parliament, the formation of a “Marriage Reform League” to “organize the agitation and petitioning,” and refusal by couples to enter into legal marriage until there was legal change (34-35). Instead of entering into a marriage contract with conditions determined by Parliament, Besant proposed that couples determine for themselves the conditions of their marriage, with the emphasis that marriage is a partnership.

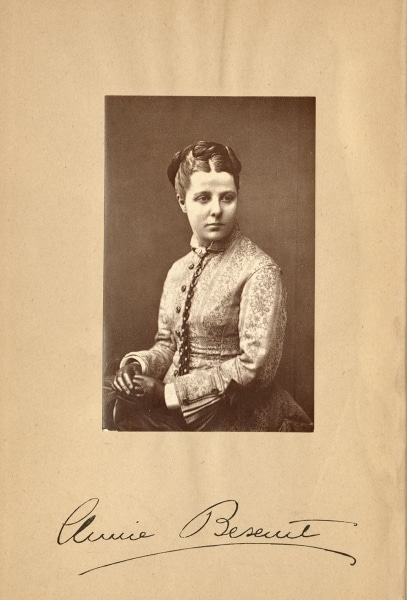

Portrait of Annie Besant, from the published trial transcript for The Queen v. Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant (1877). Gift of Michael Zinman. LCP 106454.D

One of the consequences of marriage that Besant describes is the wife’s loss of control over her body. She writes that “no rape can be committed by a husband on a wife; the consent given in marriage is held to cover life, […] no offence is committed in the eye of the law, for the wife is the husband’s property, and by marriage she has lost the right of control over her own body” (13-14). Besant also notes that men are legally granted the ability to beat their wives as corporal punishment, a particularly cruel practice. Besant’s concerns over married women’s wellbeing, particularly the danger they were in of rape and assault, responded to the suffering of many women in the late 19th century. Furthermore, Besant’s work in marriage reform shows the need for women to have autonomy and the ability to move both freely and safely.

Besant also sought to allow women more autonomy through republishing Charles Knowlton’s 1832 book The Fruits of Philosophy: Or the Private Companion of Young People with Charles Bradlaugh in 1877. Besant met Charles Bradlaugh through a mutual colleague and her involvement in the Nationalist Secular Society and the National Reformer, of which Bradlaugh was the founder and editor respectively. The two knew that the controversial book would draw public outcry: in the preface to The Fruits of Philosophy, they defend their choice to republish the book for the sake of “free discussion” (6). Upon its republication, The Fruits of Philosophy went through several legal suits regarding its alleged obscenity for providing information on the biology of genital organs, reproduction, and birth control. Besant and Bradlaugh were arrested for violating the Obscene Publication Act of 1857, but they were acquitted on two separate occasions (1877, 1878) for not publishing the book with immoral intent.

Besant believed that women should have access to information about their bodies and have a role in family planning. The Fruits of Philosophy contains comprehensive information about female genital organs and menstruation and even a method to prevent menstrual cramps. As Besant likely recognized, Knowlton presented information likely not widely or publicly available to young women in the 19th century. Knowlton also includes theories regarding conception and contraception, notably discussing sterilization. In the preface to Besant and Bradlaugh’s republication of The Fruits of Philosophy, they promote contraception in such a way that suggests a tendency toward eugenics targeting the lower classes. They write, “We advocate scientific checks to population, because, so long as poor men have large families, pauperism is a necessity, and from pauperism grow crime and disease” (8). Addressing Besant’s interests, they do acknowledge that “[i]t is not only the hard-working classes which are concerned in this question […] The woman’s health is sacrificed and her life embittered from the same cause” (8-9). While Besant worked throughout her lifetime to grant oppressed people self-autonomy, it is valuable to consider that she, as a White woman, assumed that she could speak with authority and impose her own vision of progress on others.

Nevertheless, Besant echoed the voices of women in abusive marriages in the 19th century, and her work continues to reflect women’s claim to self-autonomy and liberty today. In Marriage: As It Was, As It Is, and As It Should Be, Besant urges her readers to prioritize change over social taboo, writing, “Reforms have never been accomplished by Reformers who had not the courage of their opinions” (36). The book and others were published on both sides of the Atlantic, and the Library Company of Philadelphia currently holds an 1878 copy of The Law of Populations: Its Consequences and Its Bearing upon Human Conduct and Morals, an 1879 copy of Marriage: As It Was, As It Is, and As It Should Be, and an 1890 copy of Knowlton’s The Fruits of Philosophy that was edited by Besant and Bradlaugh. Her words are particularly resonant today, as movements within the United States look to reform systemically oppressive institutions.

Lydia Shaw, Franklin & Marshall Class of 2022

Works cited

“Annie Besant (1847-1933).” BBC, accessed June 22, 2020, http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/besant_annie.shtml.

Meek, Caroline, and Claudia Nunez-Eddy, “Annie Wood Besant (1847-1933).” Last modified December 7, 2017. https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/annie-wood-besant-1847-1933.

Besant, Annie, Marriage: As It Was, As It Is, and As It Should Be: A Plea for Reform. London: Freethought Publishing Company, 1882. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wau.39352031064702&view=1up&seq=7.

Bradlaugh, Charles, and Annie Besant. Fruits of Philosophy: A Treatise on the Population Question. San Francisco: The Reader’s Library, 1891. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Fruits_of_Philosophy/60DIWglaAsoC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=annie+besant+contraception&printsec=frontcover.