Book conservator Todd Pattison and Library Company Cataloger Arielle Rambo co-wrote an article on book binder Benjamin Bradley and the cataloging of 19th-century bindings. The article is slated to be published in late 2015 in Volume 3 of Suave Mechanicals: Essays on the History of Bookbinding. Arielle Rambo previously wrote about the collection of Benjamin Bradley bindings for our Beyond the Reading Room blog, reproduced below:

The Todd & Sharon Pattison Collection of Signed Benjamin Bradley Bindings has been my first project as a rare book cataloger at the Library Company of Philadelphia. As a relative newcomer to the world of cataloging, I feel fortunate to cut my teeth on such an interesting and gorgeous set of publishers’ bindings.

The cloths on Bradley-bound books range from stunning ribbon-embossed flowers, vines, fruits, and abstract patterns to plain bookcloth with custom stamping on the covers and spines. Bradley was likely the first binder to advertise on cloth covers, using a special die to stamp his name into many of the books bound in his bindery.

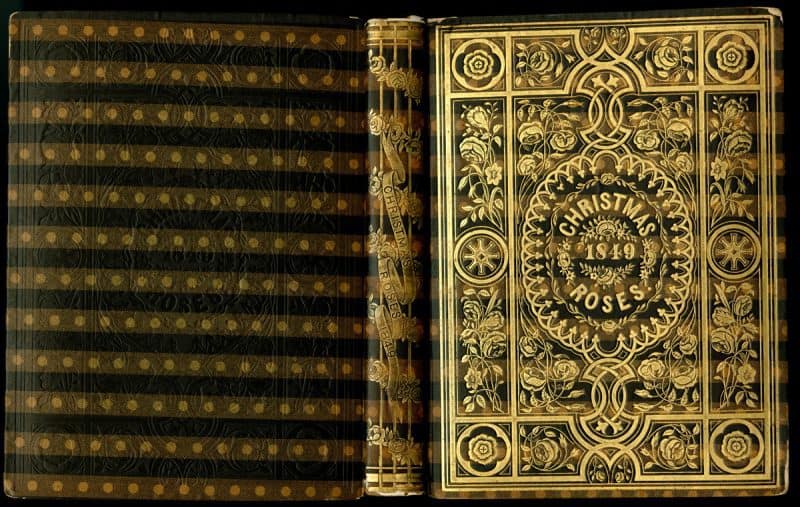

A particularly ornate Bradley-bound book using my favorite of Bradley’s bookcloths. This binding features gold blocking on the front cover and spine, and blind blocking on the back cover.

By signing his books, Bradley became known for the decorative elements of his bindings. The visual impact of a Bradley-bound book made him the leading cloth case binder in New England by the end of the 1830s. His ability to bind beautiful, quality books quickly and relatively inexpensively helped develop the acceptance of cloth-bound books, and established the material’s dominance as the chief covering for a variety of printed texts.

B. Bradley Binder stamped on the front cover of Six Months in a Convent.

Bradley owed much of his success to the production of a single book:Six Months in a Convent, or The Narrative of Rebecca Theresa Reed, published in Boston by Russell, Odiorne & Metcalf in 1835. The book became the first anti-Catholic bestseller in America, with more than 50,000 copies sold in the first year of publication.

Rebecca Theresa Reed was raised Protestant in Charlestown, Massachusetts, but converted to Catholicism in 1831 at the age of nineteen. She entered an Ursuline convent in her hometown that same year. According to her account, Reed suffered and was witness to cruel treatment within the walls of Mount Benedict convent, forcing her to escape and return to her Protestant family and beliefs after only six months in residence.

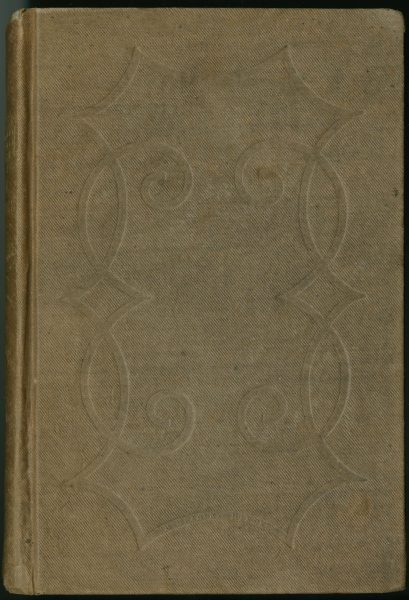

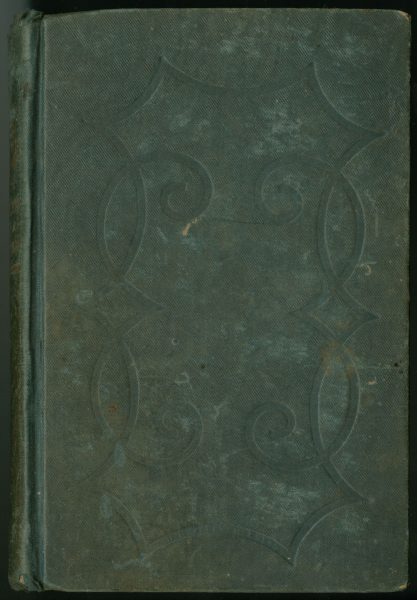

Six Months in a Convent bound in plain bookcloth.

The introduction to Six Months compares the effect of Reed’s account to Martin Luther’s call for Reformation within the Roman Catholic Church in 1520. Though this comparison seems extreme, Reed’s account certainly made waves both locally and internationally. In 1834, two years after Reed’s departure, a mob set fire to Mount Benedict convent, burning it to the ground. Reed’s account would not be published for another year, but her narrative had already become quite public within her community. The Ursulines directly blamed Reed for the attack on the convent, and claimed the description of her time at Mount Benedict to be absolute fiction.

Six Months in a Convent showing variance in bookcloth color.

Obviously, Six Months in a Convent had a much more positive effect on Bradley’s bindery. For Bradley to have produced over 50,000 copies of Six Months less than two years after the 1833 fire that destroyed nearly all his machines and tools is remarkable to say the least. To offset the losses caused by the fire, Bradley was forced to rethink his methods in order to stay in business. By breaking the binding process down into specific steps to be performed by unskilled workers, Bradley was able to sidestep the traditionally long apprenticeship required for bookbinders, and create an assembly-line process for manufacturing. Six Months in a Convent is evidence of this revolutionary approach to bookbinding.

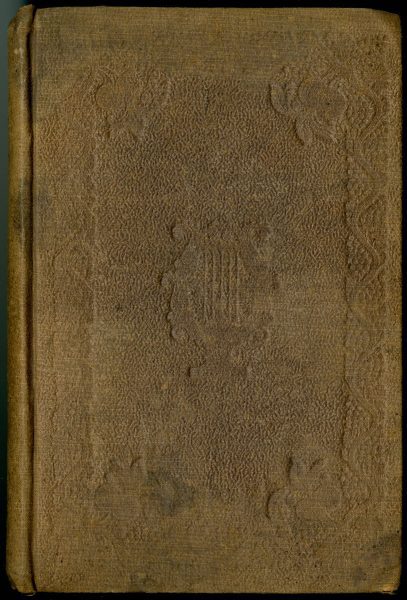

Most copies of Six Months in a Convent feature the same ornamental stamping shown in the images above. This copy features Bradley’s lyre stamped on the front cover.

Whether Rebecca Reed’s narrative is founded in fact or fiction is not for me to say. However, it is undeniable that the production of this one book made it possible for Benjamin Bradley’s business not only to continue, but to flourish.