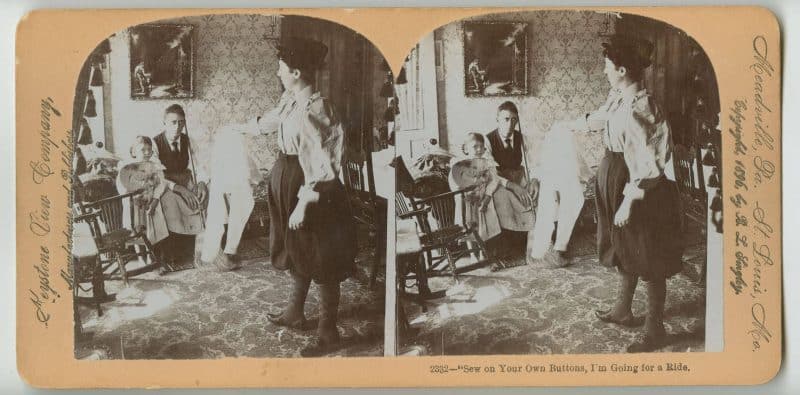

“Sew on Your Own Buttons, I’m Going for a Ride!”

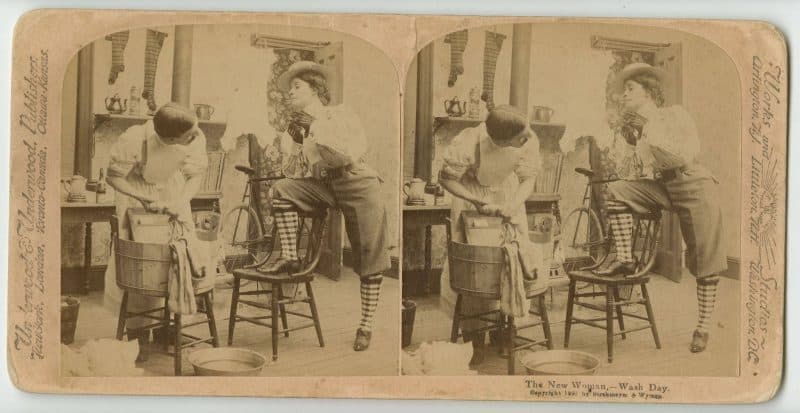

The New Woman – Wash Day, c. 1901

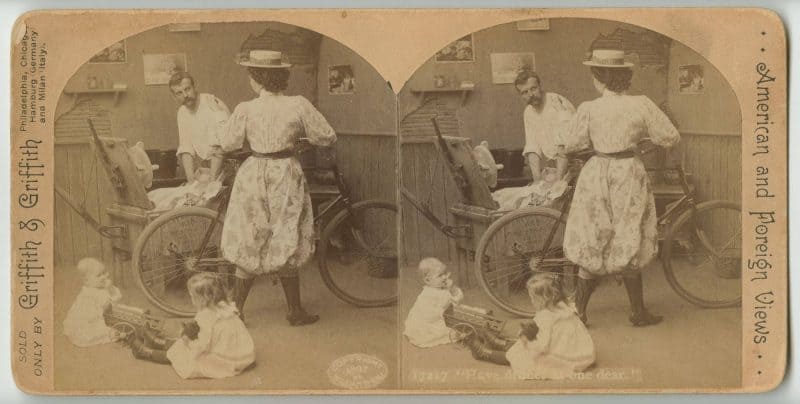

William Herman Rau, Have Dinner at One Dear, c. 1897

Sew on Your Own Buttons, I’m Going for a Ride. c. 1896

Melody Davis. “The New Woman in American Stereoviews, 1871-1905,” in Elizabeth Otto and Vanessa Rocco, eds., The New Woman International: Representations in Photography and Film from the 1870s through the 1960s. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/d/dcbooks/9475509.0001.001/1:4/–new-woman-international-representations-in-photography?g=dculture;rgn=div1;view=fulltext;xc=1#4.1

1314 Locust St., Philadelphia, PA 19107

TEL 215-546-3181 FAX 215-546-5167

http://www.librarycompany.org

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!