Songs of the 19th Century

Similar inferences can be made from the collection of 19th-century sheet music I have been working with over the past month. This collection was an anonymous gift to the Library Company, and one of my jobs, with the help of Rachel D’Agostino, Curator of Printed Books, was to sort through the music and take inventory in order to better understand this collection. What unites most of the volumes in this collection—apart from a few piano exercise books and anthologies of works by particular composers—is that they are personal expressions and interpretations of society’s trends and concerns at the time in which they were compiled. For example, it shows that even during (and in the long years before) the Civil War, when the nation was splintering apart, people still turned to music for entertainment, and perhaps solace. “The Vacant Chair,” a song lamenting the loss of a son in combat during the Thanksgiving holiday, vividly represents this, as do many other songs present in some volumes from the 1860s, such as early versions of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

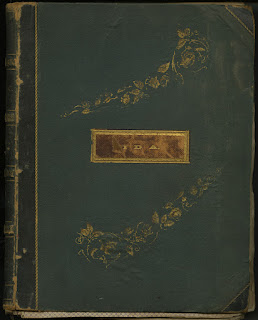

The more miscellaneous elements of the musical collection, after examination, become telling in themselves. In any given volume in this collection, one may find comic songs (and, in some cases, minstrel songs); marches and arias from well-known European operas (such as Bellini’s Norma, which premiered in 1831); works of the breathtaking talents of 19th- century greats destined to be remembered, such as Mendelssohn and Schumann; popular ballads sold in bulk from prominent publishing houses (some of the music of which was set to poetry, such as the Romantic, spiritual words of Shelley); waltzes, gallops, and polkas; and many examples of the mazurka, which, in the earlier half of the century, Frédéric Chopin used to advance the cause for Polish nationalism. The collection shows that music was a backdrop to many aspects of 19th-century American life, both public and national and private and personal. It is suspected that some of the books may have belonged to the family of noted lawyer and American Civil War diarist George Templeton Strong, whose support of the Union may be reflected in certain Civil War songs, but whose family’s other tastes seem to run to pieces by great composers such as Schubert –contained in volumes titled “Kammer-Musik,” or “Chamber Music,” kept by what seems to be a well-traveled and cultured son— and ballads to be practiced, sung, taken in, and enjoyed in the salon, perhaps in the company of other amateur musicians.

Such a musical melting pot not only tells us what the owners of the bound volumes liked to play and share, although, as any present-day musician or lover of music can assert, that is very important too. This music could give us a clue as to how individuals and families dealt and engaged with events happening in their world, from the almost all-encompassing Civil War to other more transient interests in 19th-century America. With music becoming a more accessible form of expression for many people in the 19th century, it is imperative that we look to it for answers to questions or concerns of the times as we would look to other available means of expression, such as writing. Like the rest of the books in the Library Company stacks, music offers its own stories of history from the ordinary people who lived with and through it.

Jill Hanley

Library Company of Philadelphia Volunteer Intern

1314 Locust St., Philadelphia, PA 19107

TEL 215-546-3181 FAX 215-546-5167

http://www.librarycompany.org

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!