New Context for Teaching Science to African American Girls in Early Philadelphia

New Context for Teaching Science to African American Girls in Early Philadelphia

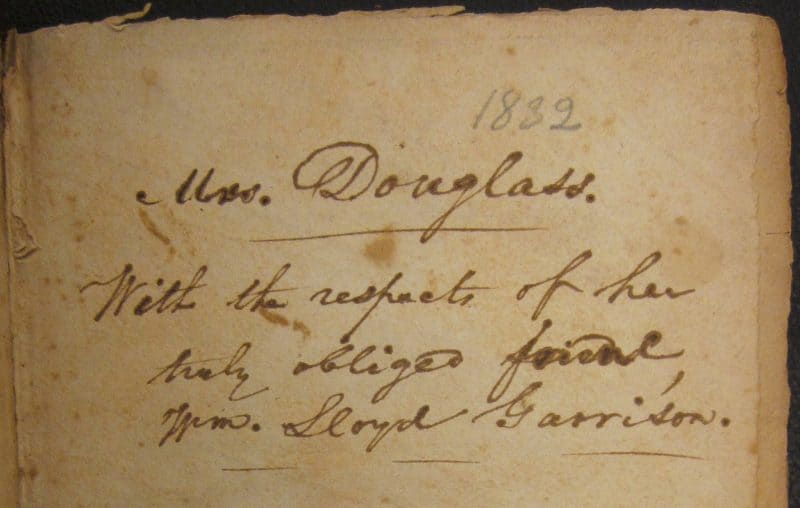

The Library Company recently acquired an important copy of Jane Kilby Welsh’s two-volume Lectures on Mineralogy and Geology (Boston, 1832-33) inscribed by William Lloyd Garrison, editor of The Liberator and proponent of immediate emancipation, to Grace Bustill Douglass (1782-1842), African American educator and founding member of the biracial Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. It is furthermore inscribed by Grace’s daughter and fellow abolitionist, Sarah Mapps Douglass (1806-1882). These volumes not only complement the Library Company’s existing holdings related to Sarah Mapps Douglass, but help to flesh out an important historical gap regarding the nature of science pedagogy at Sarah’s school for African American girls.

![Inscription on flyleaf by to G. [Grace] Douglass from W. L. [William Lloyd] Garrison. Lectures, v. 2.](http://librarycompany.org/wp-content/uploads/Welsh_v2_Garrison-sig_crop-1-800x414.jpg)

Inscription on flyleaf by to G. [Grace] Douglass from W. L. [William Lloyd] Garrison. Lectures, v. 2.

Independent of the volumes’ provenance, Welsh’s Lectures on Mineralogy and Geology is an uncommon title that can be useful for thinking about the history of women and science in early America. Although a relatively obscure figure, Welsh’s scientific interests and aims can be discerned from her pedagogical writing and provide important context for reconstructing the Douglasses’ use of her work.

Jane Kilby Welsh was probably the daughter of John Welsh, a Boston merchant who died in 1789. She spent part of her adult life in Northampton, Massachusetts. Her earliest known written work is A Botanical Catechism: Containing Introductory Lessons for Students in Botany (Northampton, Mass., 1819), a rudimentary question-and-answer introduction to the Linnaean system of classification. Renowned science educator and author Almira Hart Lincoln Phelps (1793-1884) admired her predecessor in scientific writing, believing the work to be “the first attempt by an American lady to illustrate the science.” This was not Welsh’s only work on botany. A review of Lectures on Mineralogy and Geology appearing in The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal identifies Welsh as the author of The Pastime of Learning, with Sketches of Rural Scenes (1831), a dialogue book documenting the botanical pursuits of “Mr. and Mrs. G” and their children. Sophisticated botanical knowledge is disseminated through a domestic narrative that would have been compelling to young readers.

Lectures on Mineralogy and Geology continues the story of the “G” family as they learn how to collect and evaluate rocks, minerals, shells, and fossils. To write Lectures, Welsh corresponded with prominent geologists, including Edward Hitchcock (1793-1864) of Amherst. Like many women scientific writers of her time – and indeed, men like Hitchcock — Welsh believed the pursuit of scientific knowledge was a spiritual process that confirmed intelligent design. Paraphrasing Alexander Pope in her preface, Welsh hoped that “the youthful mind, while thus exploring the works of nature, will be elevated with gratitude, adoration, and love, to the view of Nature’s God.”

Garrison and the Douglass Family

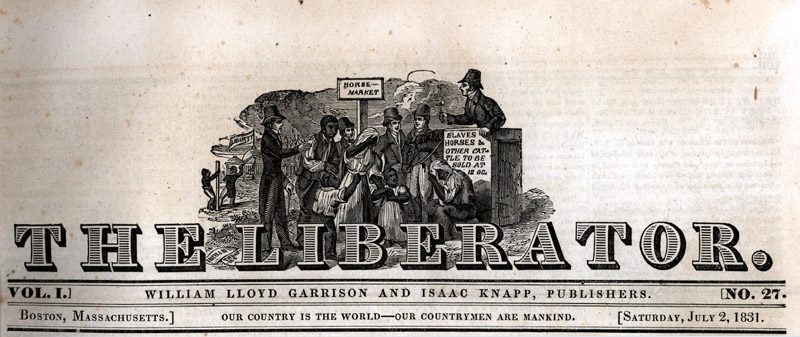

Masthead from The Liberator (Boston, 1831).

William Lloyd Garrison (1805-79) was a recent convert to immediatism when he met the Douglasses, a relatively well-off African American family from Philadelphia, in the early 1830s. Through both activism and teaching, Grace Douglass and her daughter Sarah had worked to improve educational opportunities for free African Americans in Philadelphia. In 1819, Grace Douglass and James Forten (1766-1842) co-founded a school, where Sarah Douglass may have taught for the first time as an assistant teacher. When Sarah was twenty-one years old, she took control of a school established by the Augustine Education Society. Thus, by 1831, when Sarah took up a collection for Garrison’s newly-founded abolitionist paper, The Liberator, she was already an experienced teacher.

Grace and Sarah Douglass may have first met Garrison in June 1831, when he was traveling to Philadelphia to address the free African American community. Correspondence between Sarah Douglass and Garrison regarding the Female Literary Association, a Philadelphia writing group for African American women, suggests that Garrison and the Douglass family were on friendly terms by early 1832. That summer Garrison was back in Philadelphia, visiting with the Douglass family. By the end of the year, Garrison had likely learned of Sarah and Grace’s scientific interests and teaching strategies.

Inscription on flyleaf by William Lloyd Garrison. Lectures, v. 1.

In late 1832, someone at The Liberator, possibly Garrison, read and favorably reviewed Jane Kilby Welsh’s Lectures on Mineralogy for the November 3 issue. Few books were reviewed for the paper, although there was a running commentary on a Boston-based journal called The Naturalist. Although the reviewer occasionally dissented with The Naturalist’s characterization of race – the reviewer refused to believe that the condition of African Americans was biological, but rather was the product of poor treatment – he generally commended the work. Welsh’s book may have been highlighted because it was consistent with The Liberator’s practice of reviewing didactic or useful works of science. Welsh’s theological perspective, too, may have been appealing; her geological narratives supported a single-origin, universal creation of man that would have resonated with the reviewer who found fault with The Naturalist’s support of polygenesis. Regardless of the reason, Garrison seemed sufficiently pleased with the work that he gave it to Grace Douglass as a gift. Perhaps he gave her the very copy that was reviewed for The Liberator.

![Inscription on title page by S. M. [Sarah Mapps] Douglass. Lectures, v. 2.](http://librarycompany.org/wp-content/uploads/Welsh_v2_Douglass-SM-sig-1-377x600.jpg)

Inscription on title page by S. M. [Sarah Mapps] Douglass. Lectures, v. 2.

Sarah Mapps Douglass’s Mineral Cabinet and Teaching Science

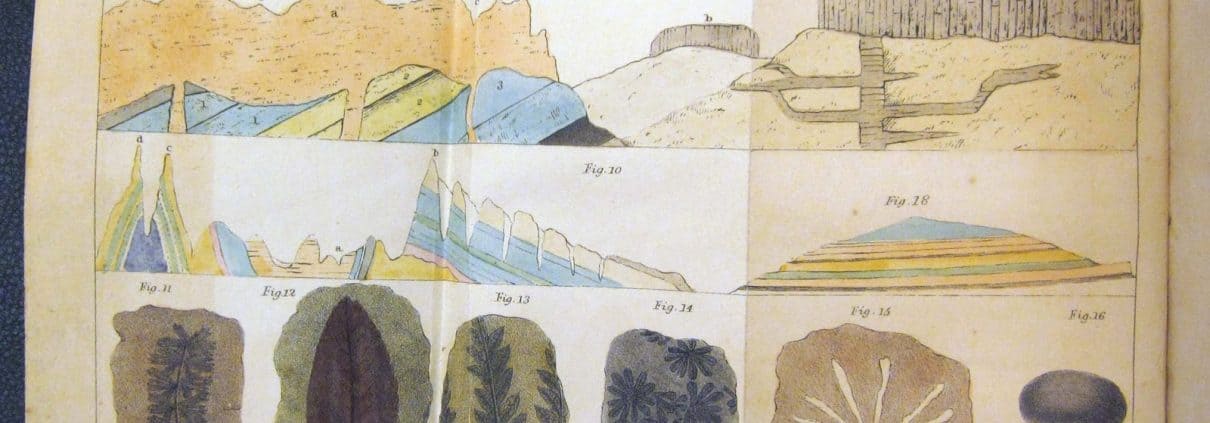

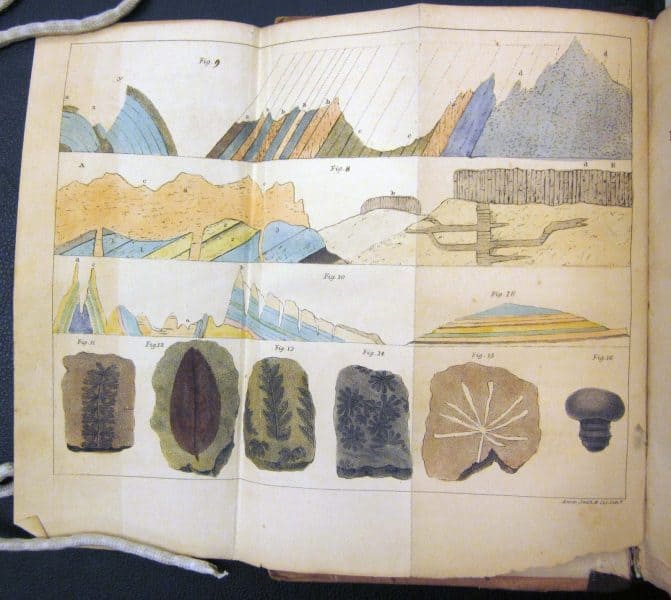

Hand-colored plate. Lectures, v. 2.

Given how little we know about the specifics of her pedagogy, Sarah’s personal copy of Lectures on Mineralogy is an exciting discovery. Sarah Mapps Douglass very probably used Welsh’s booksin her classroom. Newspaper accounts from the 1830s report that Sarah maintained a mineral cabinet to teach mineralogy to her students. This cabinet, or a similar one, followed her to the Institute for Colored Youth, where she later taught. Sarah would have curated this cabinet herself, collecting and labeling specimens before presenting them to her students for analysis. She may have learned to do this from Welsh’s books, in addition to using them as the basis for lectures. As a private institution serving the city’s recently freed black population, Sarah’s school struggled to raise revenue to maintain operations, often seeking aid from the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society to keep the institution afloat. With funds dear, Garrison’s gift would have been a welcome resource. Furthermore, a book written by a woman may have seemed an appropriate choice for teaching girls.

While nowadays we might look askew at scientific justification of creationism, it is important to remember that Welsh’s intermingling of science and religion was not unusual for this period, and this should not detract from any sound instruction regarding the practice of mineralogy in Lectures. Welsh is our best opportunity to reconstruct the complexities of Sarah Douglass’s scientific process. Sarah Douglass did not simply pick up rocks; she would have known how to read the landscape, using contextual geological clues to locate prized specimens.

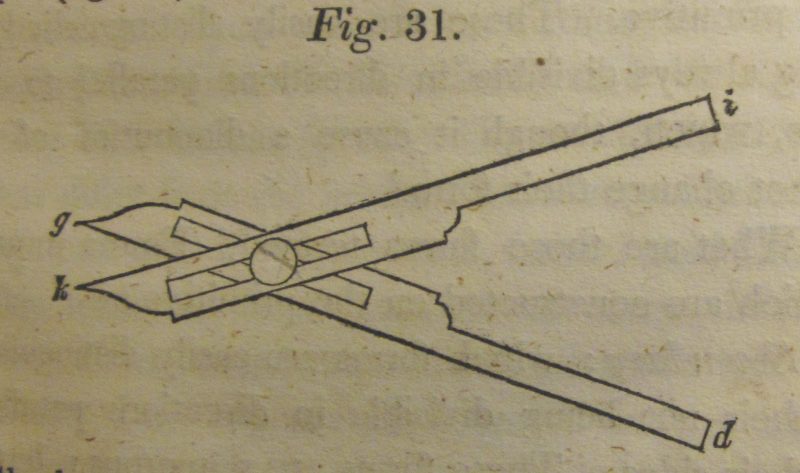

Diagram of shears. Lectures, v. 1.

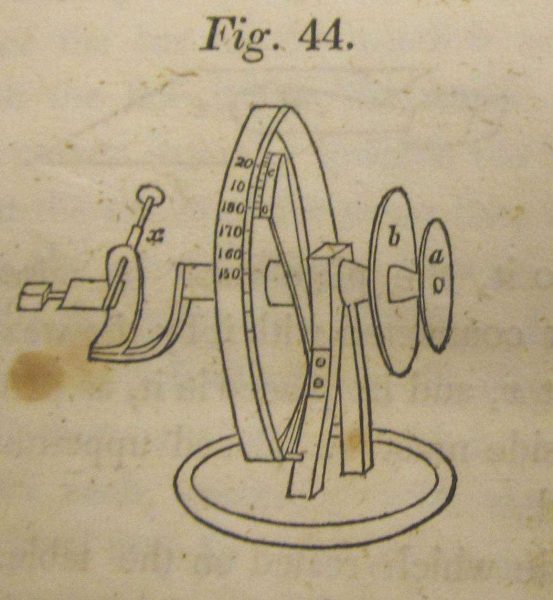

She also would have known how to use a variety of mineralogical tools. Welsh’s discussion of scientific instruments reveals the labor and knowledge used to create Sarah’s mineral cabinet. Mineralogists considered many factors when identifying specimens. One such factor is a mineral’s cleavage, the tendency to break along smooth planes. Welsh’s text depicts instruments meant to facilitate mineral analysis, including illustrations of shears used to break rocks along cleavage lines and a goniometer to measure crystal angles. Teachers often used such tools in practical demonstrations to familiarize students with technical language. It is one thing to abstractly define cleavage – it is another to demonstrate what it looks like in class.

Diagram of a goniometer. Lectures, v. 1.

While teaching her students the rudiments of mineralogy, Douglass likely reminded her students that learning science could bring them closer to God. It seems clear that she shared Welsh’s theological outlook, as a report of her school in the December 2, 1837 issue of The Colored American echoed the preface to the book:

Scholars will be able to make a more nuanced assessment of the meaning of this comment through a close reading of Welsh’s writing, coupled with a reconstruction of how her book may have been used in its day.

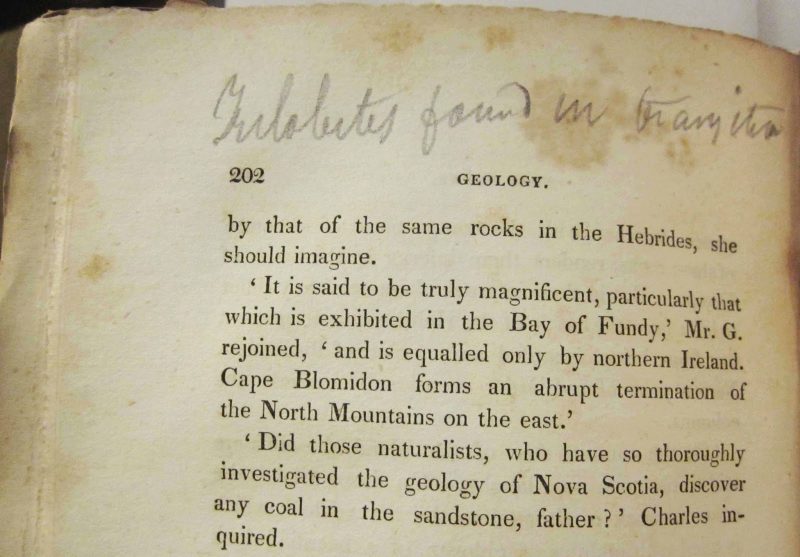

Annotations and Afterlife

In addition to the inscriptions identifying Grace and Sarah Mapps Douglass as former owners, the books contain pencil annotations commenting on the text. The annotator appears to be knowledgeable of early geological and paleontological discoveries, adding his or her thoughts on trace fossils, trilobites (extinct marine invertebrates from the Paleozoic Era), and the general nature of petrifactions (the process in which organic material is converted into a fossil). The annotator also approved of biblical scholar Granville Penn’s theories of Mosaic geology, praising his work in the book’s margins. There is consistency here regarding the interrelationship between science and religion that makes one hopeful that the annotations belong to Grace, Sarah, or one of their students. Penn’s theological take on geology was most certainly out of vogue by the time the book ended up at David McKay’s Old Bookstore in the late nineteenth century, making subsequent owners a less likely fit.

Annotation on trilobites from Lectures, v 2.

Perhaps a reader can identify the handwriting sample? Could these inscriptions be in an informal hand belonging to Garrison or the Douglasses? Do they belong to one of Sarah Mapps Douglass’s students? If you have any insight, leave a message in the comments below.

PhD Candidate in History, University of Connecticut

1314 Locust St., Philadelphia, PA 19107

TEL 215-546-3181 FAX 215-546-5167

http://www.librarycompany.org