Treasures from the Library Company of Philadelphia

One of the most popular poets in colonial America, Phillis Wheatley became the first person of African descent to publish in America. The enslaved Wheatley earned international fame for an elegy for George Whitefield, the renowned Methodist minister of the Great Awakening, whom she had seen preach in Boston shortly before his death in 1770. Wheatley is just one of hundreds of African American authors, illustrators, engravers, and photographers whose works reside at the Library Company of Philadelphia.

How did a library founded by Benjamin Franklin amass such an extensive collection of African Americana? Ranging in date from the mid-16th century into the early years of the 20th century, the collection contains books, pamphlets, newspapers, periodicals, broadsides, and graphics that were acquired over the course of our almost 300-year history. Until recently, the growth of the African Americana collection was largely what our late librarian Edwin Wolf 2nd termed “the result of miscellaneous accumulations.”

In some instances, authors donated copies of their works to be read by the influential Philadelphians who were Library Company members. Such was the case for Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, who donated a copy of their pamphlet, A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the Year 1793: And a Refutation of Some Censures, Thrown upon Them in Some Late Publications, which was likely the first instance of African Americans receiving a copyright in the United States. Beginning a strong tradition of black protest literature, Jones and Allen disputed the unjust claims of leading Philadelphian Mathew Carey, who accused African Americans of price gouging and pilfering during the city’s horrific 1793 Yellow Fever Epidemic. In reply, Jones and Allen documented the bravery of Philadelphia’s black community, which worked with physician Benjamin Rush in coordinating large-scale efforts to nurse the sick and to bury the dead across racial lines, often at the cost of their own health and lives.

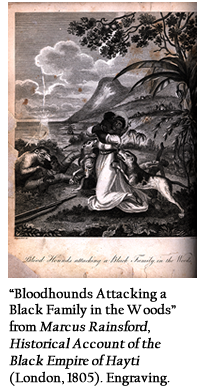

In addition to printed works by African American individuals and organizations, another area of strength is the documentation of the rise of slavery in the New World along with the rise of movements against slavery. The Library Company’s membership of Quakers and abolitionists helped attract donations of antislavery literature. Eighteenth-century antislavery activists such as Anthony Benezet and Granville Sharp gave their prolific output of pamphlets and those of their friends. During its first century, many of the Library Company’s Directors were also members or Directors of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery, making the Library Company a fitting site for depositing the Society’s annual reports and other printed materials for preservation. Following suit, reports of other abolition and colonization societies, philanthropies, schools, asylums, and relief agencies were also sent in by these organizations or their patrons.

In addition to printed works by African American individuals and organizations, another area of strength is the documentation of the rise of slavery in the New World along with the rise of movements against slavery. The Library Company’s membership of Quakers and abolitionists helped attract donations of antislavery literature. Eighteenth-century antislavery activists such as Anthony Benezet and Granville Sharp gave their prolific output of pamphlets and those of their friends. During its first century, many of the Library Company’s Directors were also members or Directors of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery, making the Library Company a fitting site for depositing the Society’s annual reports and other printed materials for preservation. Following suit, reports of other abolition and colonization societies, philanthropies, schools, asylums, and relief agencies were also sent in by these organizations or their patrons.

![[The King of Benin and his army] from John Ogilby, Africa: Being an Accurate Description of the Regions of Aegypt, Barbary, Lybia, and Billedulgerid: the Land of Negroes, Guinee, Aethiopia, and the Abyssines(London, 1670). Woodcut.](http://www.librarycompany.org/treasures/essays/ad12/Wing0163-14.png) The African Americana collections grew further as the Library Company additionally purchased materials to meet contemporary readers’ interests in abolitionist literature as well as in such subjects as history, religion, travel, and biography. In keeping with this practice, in 1759, Peter Collinson, the Library Company’s London purchasing agent, procured Africa: Being an Accurate Description of the Regions of Aegypt, Barbary, Lybia, and Billedulgerid, the Land of Negroes, Guinee, Aethiopia, and the Abyssines (London, 1670) by John Ogilby, whose oeuvre Collinson deemed “very proper for a public Library.” Largely an English translation of a Dutch book, neither Ogilby nor the work’s original compiler, Dutch geographer Olfert Dapper, had ever been to Africa, calling into question the title’s claim to accuracy.Nevertheless, this compilation of journals and other travel accounts, filled with richly engraved illustrations and maps, is representative of the era’s European knowledge of and views on Africa. Works of this genre are now valuable for scholarly research into the development of racial thought and racism as well as the Western discovery and exploitation of Africa.

The African Americana collections grew further as the Library Company additionally purchased materials to meet contemporary readers’ interests in abolitionist literature as well as in such subjects as history, religion, travel, and biography. In keeping with this practice, in 1759, Peter Collinson, the Library Company’s London purchasing agent, procured Africa: Being an Accurate Description of the Regions of Aegypt, Barbary, Lybia, and Billedulgerid, the Land of Negroes, Guinee, Aethiopia, and the Abyssines (London, 1670) by John Ogilby, whose oeuvre Collinson deemed “very proper for a public Library.” Largely an English translation of a Dutch book, neither Ogilby nor the work’s original compiler, Dutch geographer Olfert Dapper, had ever been to Africa, calling into question the title’s claim to accuracy.Nevertheless, this compilation of journals and other travel accounts, filled with richly engraved illustrations and maps, is representative of the era’s European knowledge of and views on Africa. Works of this genre are now valuable for scholarly research into the development of racial thought and racism as well as the Western discovery and exploitation of Africa.

In the late 1960s Librarian Wolf launched a concerted effort to build the more than two-centuries-long “miscellaneous accumulations” into a corpus of black history material. Scholars and researchers, moved by post-war African American civil rights activism, began to reexplore the significance of slavery in the American story and rediscovered the importance of the writings of African Americans, long neglected by academic scholars. In 1969 we joined with our neighbor institution the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in mounting a major exhibition of our holdings, “Negro History, 1553 – 1906.” On the heels of the exhibition, the Library Company and the Historical Society secured a three-year grant to identify and catalog our African American-related holdings and in 1973 published our findings in a printed catalog Afro-Americana: 1553-1906. In the same period, far ahead of other American history collecting organizations, the Library Company began actively acquiring African Americana as it became available, thereby adding substantially every year to already remarkable holdings.

![Sarah Mapps Douglass, [“I Love a Flower”], from the Amy Matilda Cassey album, ca. 1833. Watercolor and gouache.](http://www.librarycompany.org/treasures/essays/ad12/cassey-album-p-9764-p9.png) Among our recent acquisitions are three 19th-century African American women’s friendship albums by Amy Matilda Cassey and the sisters Mary Anne and Martina Dickerson. The three volumes, of only four of their kind known, provide unique insights into the culture, politics, and gender relationships of free African American women of the antebellum era. Cassey, the Dickersons, and the women in their circles studied drawing manuals, decorative floral works, women’s periodicals, and the “language of flowers” literature, while at the same time they challenged slavery in public meetings, defied public opinion with their racially integrated organizations, published antislavery pamphlets, held antislavery fundraising fairs, and petitioned Congress for the immediate abolition of slavery. The albums contain essays, poetry, sketches, and floral watercolors contributed by figures prominent in the antislavery movement, including Sarah Mapps Douglass, Margaretta Forten, Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Wendell Phillips, to name a few. These recently digitized albums inaugurate our newly created African Americana Digital Collection.

Among our recent acquisitions are three 19th-century African American women’s friendship albums by Amy Matilda Cassey and the sisters Mary Anne and Martina Dickerson. The three volumes, of only four of their kind known, provide unique insights into the culture, politics, and gender relationships of free African American women of the antebellum era. Cassey, the Dickersons, and the women in their circles studied drawing manuals, decorative floral works, women’s periodicals, and the “language of flowers” literature, while at the same time they challenged slavery in public meetings, defied public opinion with their racially integrated organizations, published antislavery pamphlets, held antislavery fundraising fairs, and petitioned Congress for the immediate abolition of slavery. The albums contain essays, poetry, sketches, and floral watercolors contributed by figures prominent in the antislavery movement, including Sarah Mapps Douglass, Margaretta Forten, Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Wendell Phillips, to name a few. These recently digitized albums inaugurate our newly created African Americana Digital Collection.

In furtherance of our commitment to the African Americana Collection, in 2007 the Library Company established the Program in African American History, which supports fellowships, conferences, exhibitions, publications, public programming, teacher training, and acquisitions to achieve the full potential of our considerable holdings in this area.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!