Tomorrow is Women’s Equality Day!

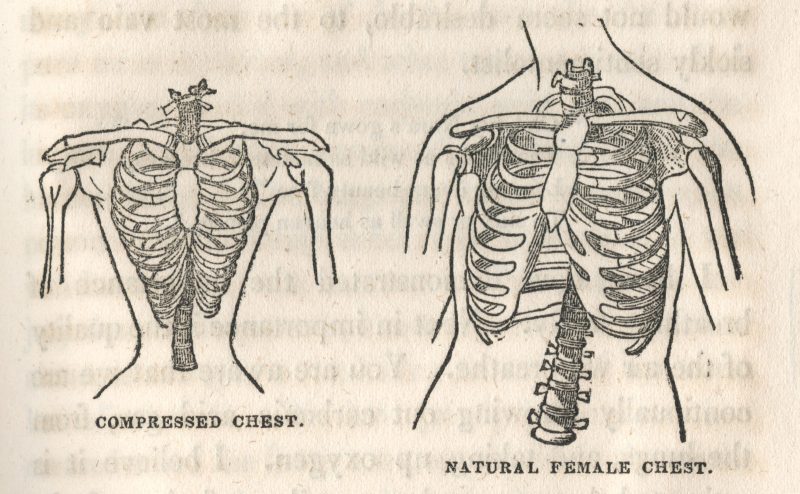

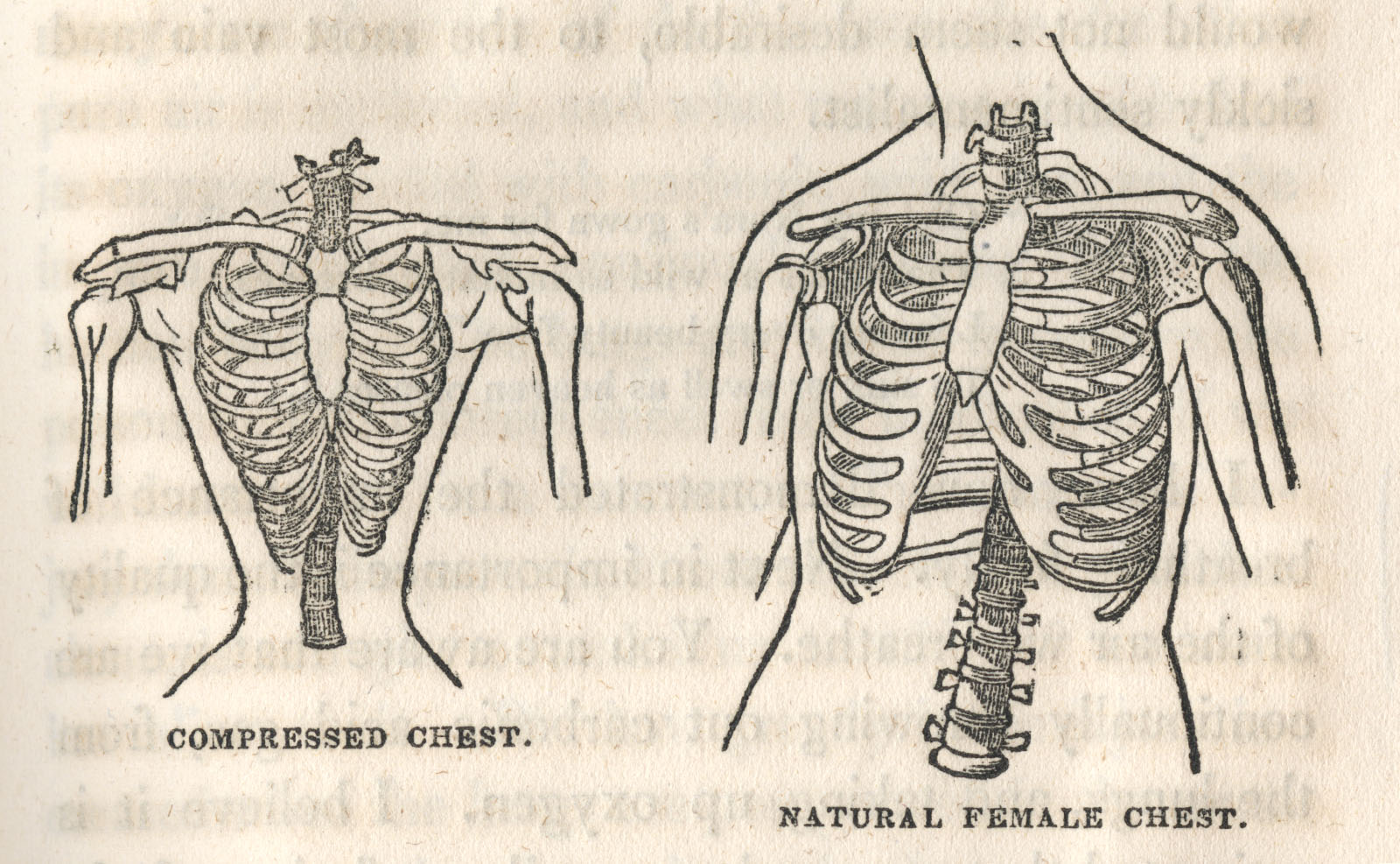

Illustration in Mary Gove Nichols’s Lectures to Ladies on Anatomy and Physiology (Boston, 1842).

As a Library Company volunteer, Lydia Shaw, a rising senior at Friends Select School, has undertaken the study of Mary Sargeant Gove Nichols (1810-1884) this summer. Although she died long before the certification of the 19th Amendment on August 26, 1920, Mary Gove Nichols is a stand-out example of a 19th-century woman who promoted equal rights for women.

According to Lydia:

Mary Gove Nichols’s Lectures to Ladies is a compilation of her lectures to women on their bodies and health. A health and marriage reformer, Mary wanted women to learn more about their own anatomy, so they would be able to have more control over their bodies. Mary herself was plagued with consumption her whole life. Her sister died of consumption at the age of twenty-one, which Mary argued was exacerbated by wearing a tight-laced corset and exposure to harsh weather. In her lectures, she warned women of corsets and highlighted the effects of popular fashion on the body.

But Mary also explored many, many other topics and movements.

Mary Gove Nichols was most definitely a force to be reckoned with, and reckoned with she was. An important woman of the mid-19th century, she was both a radical and a loving mother and wife. Mary was a health reformer, a marriage reformer, a free love advocate, a women’s rights advocate, a fiction writer, a lecturer, an editor, a teacher, a repeat religious convert, a devout Catholic missionary, a Spiritualist, and an entrepreneur. She lived in a time when women were not readily accepted as intellectuals, and she made sure to create spaces for her ideas and herself to thrive. One such place was in fiction, for which she used her creative skills to not only tell an excellent story, but to teach what she saw as important lessons–lessons that people did not widely agree with, especially coming from a woman.

Mary was born in 1810 in a New England town which she characterizes as “ugly” and “weather-beaten” in her autobiographical novel Mary Lyndon, or, Revelations of a Life. She found it hard to interact successfully with most of her family. Her elder brother and sister, she claimed, were nothing like her. Mary’s mother was not traditionally kind and loving, and discouraged her daughter’s love of novels, reminding her constantly that usefulness around the home was more important. It was her father whom she felt the most affection for. An outspoken man with radical opinions, he encouraged critical thinking and reading skills in his daughter, but he did not allow her to learn to write. However, Mary learned to write anyway.

In her mid-teenage years, Mary’s life started to change drastically. At fifteen, her sister died, and Mary turned to Quakerism for consolation. Though she was later excommunicated, Quakerism provided her comfort in the midst of depression, and led her to her first marriage, to a Quaker man named Hiram Gove. They married when she was only twenty-one, and remained married for eleven years. Hiram was an abusive husband. Mary’s relationship with him and the lack of love between them is mirrored in her fiction. Later on in life, Mary found love with a fellow intellectual, Thomas Nichols, who respected and supported her.

The nature of her relationship with Thomas can be seen in Mary’s semi-autobiographical short stories. Published under the alias “Mary Orme” in the popular literary magazine for women Godey’s Magazine and Lady’s Book, Mary’s stories were very romantic, and did not seem particularly radical for their time. One of them, “The Evil and the Good,” explores the friendship between two women throughout their lives, but also discusses social class and the importance of happiness in love and marriage. In the story, Mary describes a married couple: “They both had wealth, and they lived in and made a part of the glitter and show of the fashionable world. Were they happy?” Later, she reveals to the reader that they were not happy, but through being “gentle and kind” to each other, they might achieve happiness.

Under all of her beautiful descriptions and enticing storylines, Mary’s opinions and ideas emerge (though more clearly to the critical or informed reader). In Mary’s story “Marrying a Genius,” a character named Horace opens the story by saying, “I will not say I hate talented women, but I will say I fear them. I would never marry a genius. I want to be comfortable, and, in order to be comfortable, I want my own way; and these wise women are sure to interfere.” It is apparent from the first line that the story will discuss many of the issues Mary was interested in, such as sexism, marriage, and women’s education. Horace’s aunt, a very close relative of his, disagrees with him. She states, “I am of opinion, that the highest earthly felicity must result from a union between two highly gifted and cultivated individuals, even though the wife were equally gifted, equally educated with her husband.” Additionally, perhaps to add to her own reputation, Horace’s aunt is named Mary, which becomes a habit in Mary Nichols’s writing–naming very wise and virtuous characters after herself.

By all accounts, Thomas and Mary Nichols were very much in love, and were highly successful partners in writing, publishing, and more. They respected each other, and advocated the same causes. Thomas revered his genius wife, and did not fear her, and so they were able to fall in love and have a successful marriage.

There are many achievements Mary could be recognized for, but she remains for the most part in the shadows of those who are more widely celebrated. Mary’s efforts influenced modern feminism, but perhaps due to the fact that she lived before the feminist movement took shape, she is not featured in the limelight in the same way that women like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton are. Mary’s fiction and lectures are not easily found anymore. However, the world has undergone much change since her Lectures to Ladies. Though women’s rights to their own bodies are still being disputed, marital rape–something Mary suffered by the hands of Hiram Gove–is now illegal, and women have more power in their marriages. Women with (and without) genius are given the same rights to higher education as men. And women certainly are not pressured by society to wear corsets anymore.

Works Cited

Nichols, Mary Sargeant Gove. “The Evil and the Good,” Godey’s Magazine and Lady’s Book (July 1845).

Nichols, Mary Sargeant Gove. Lectures to Ladies on Anatomy and Physiology (Boston: Saxton & Peirce, 1842).

Nichols, Mary Sargeant Gove. “Marrying a Genius.” Godey’s Magazine and Lady’s Book (September 1844).

Nichols, Mary Sargeant Gove. Mary Lyndon, or, Revelations of a Life (New York: Stringer and Townsend, 1855).

Silver-Isenstadt, Jean L. Shameless: The Visionary Life of Mary Gove Nichols, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002).