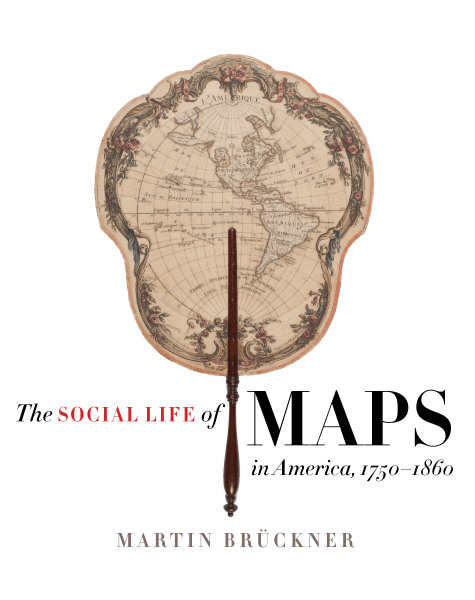

Fellow Highlight: The Social Life of Maps in America

My book, The Social Life of Maps in America, had its beginnings in a map encounter and the sudden realization that maps played a wonderfully complex role in the lives of early Americans. My map encounter was seeing Henry Popple’s luxuriously crafted A Map of the British and French Empire in America (1733) fully assembled and on display in Colonial Williamsburg. Designed as a wall map, the map measured a whopping eight by eight feet. It was not only the physically largest map showing the colonies during the long eighteenth century, but it managed to impress someone like John Adams, who, upon seeing it in Independence Hall in 1776, wrote to his wife Abigail “It is the largest I ever saw, and the most distinct. Not very accurate. It is Eight foot square!”

Coming close to shouting “Wow!,” I found the reaction to be curious because it pointed to what I thought was an uncharacteristic response for an Enlightenment-trained actor like Adams: why would the Pennsylvania Assembly hang up a super-sized and costly map that would simultaneously broadcast its very inadequacy as a map? My curiosity grew when I realized that despite the fact that the Popple map was soundly rejected by the British scientific community, it nevertheless was prominently staged in colonial state houses and by private citizens like Benjamin Franklin. Contrary to my expectation, map accuracy was not all that mattered to early Americans. Instead, they engaged with maps using multiple and often contradictory frames of reference, from way-finding tool and theatrical spectacle to empirical evidence and sentimental possession. Inspired by the diversity of map uses, I set out to track the social lives (or call it careers) of both singular maps like the Popple map and generic commercial maps by asking the twofold question: How were large and small maps embedded—real and symbolically—in American public and private life? And what did maps do—really do—for Americans?

The book’s argument is that American-made maps emerged as a meaningful media platform and popular print genre during the mid-eighteenth century precisely because the map as artifact and the concept of mapping had become involved in social relationships between people. In the course of its eight chapters—they trace the life of popular American maps from production to consumption to post-consumer uses—the book emphasizes that cartographic literacy was anything but a common competence. Reading the squiggly lines of topographical maps, following map coordinates, in short, thinking cartographically was not only a skill and habit that had to be learned and practiced, but in the process transformed maps into a major mode of social communication. Because most maps were commercial maps and were thus considered by map-makers and map-users as saleable goods, much of their value—be it informational, symbolic, or affective—came emphatically alive during the social process of exchange. Examining the social life of maps in early America allows us to comprehend more fully the expressed faith in the usability of maps as a popular tool that a large number of people embraced in order to shape their lives as individuals, citizens, or members of communities from the family to the nation.

Martin Brückner is a former Library Company Program in Early American Economy and Society Post-Doctoral Fellow and a Professor in the English Department at the University of Delaware. Professor Brückner’s current research includes work on the digital humanities project, THINGSTOR: A Material Culture Database for Finding Objects in Literature and Visual Art, and a new monograph exploring the relationship between American fiction and material culture in the long nineteenth century.