Mocking the “Other”: The Irish American Experience

This year the Print Department acquired a set of four cards mocking the experience of Irish immigrants in America. In size and appearance they are similar to advertising trade cards, but there is no particular product associated with these late 19th-century collecting cards. The set uses both visual and textual tropes to demean the Irish, playing off commonly held stereotypes that would have been readily understandable to the cards’ intended audience.

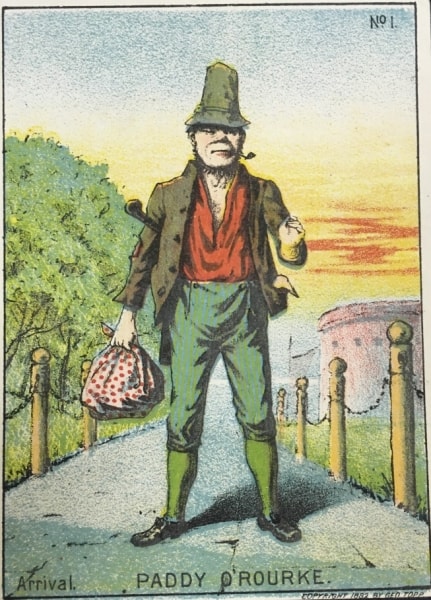

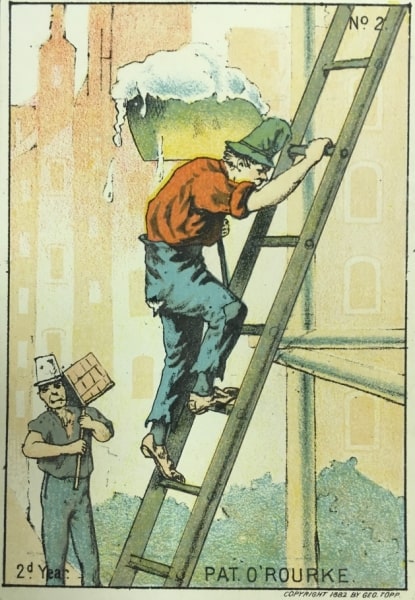

In Arrival (No. 1) Paddy O’Rourke sets foot on American soil with New York’s Castle Garden, America’s first immigration center in the background. His clothes (primarily printed in green) are ill-fitting and he carries only a small bundle, presumably all of his worldly possessions. Despite the paucity of his belongings, Paddy has brought two symbols of his Irish heritage –a tobacco pipe and a shillelagh, the traditional Irish walking stick which was also used for fighting. Card No. 2 represents the Irishman’s second year in America. He has changed his name from Paddy to Pat and has found manual employment in the urban building trades, laboring among the tall structures hinted at in the card’s background. He still wears the green cap of his homeland. His pants and shoes are worn down from his heavy labors to achieve the American dream.

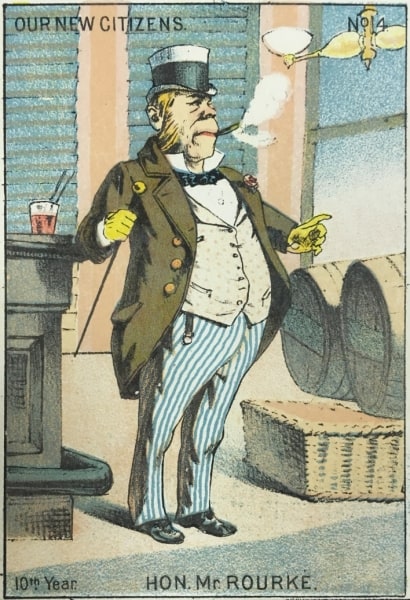

By his fifth year, our Irishman has joined the police force and is now addressed as Officer O’Rourke. He wields authority as well as a billy club as he walks his police beat in Card No. 3. At the end of his first decade in America, Officer O’Rourke has continued his journey of upward mobility to become the Hon. Mr. Rourke, implying he has entered into American politics, an option now opened to him as a newly minted United States citizen. In becoming an American, he has turned away from many of the signifiers that identified him as Irish. In Card No. 4 the clay pipe and shillelagh have morphed into a cigar and a fancy walking stick. Rourke’s corpulent body is well-dressed and he gestures confidently with an air of authority. Nonetheless, our subject is still the butt of the joke. His seat of power is the saloon and his simian-like features portray his “true” identity. Even with his Americanized name, fancy clothes, and political clout, the card shows the consumer that the Hon. Mr. Rourke is still an Irishman who drinks too much.

George Topp published this set of cards in 1882. He also issued a set of four anti-Semitic cards that year and a set of four cards satirizing German immigrants. Topp had apparently tapped into a market replete with consumers worried about the flow of immigrants into the country. Between the start of the potato famine in 1845 to 1855 alone, two million residents left Ireland, mostly coming to America. It is not surprising that many Americans felt overwhelmed by this influx of immigrants who did not quite fit in. While the Irish spoke English, they did so with an odd accent; they were largely from poverty-stricken, pre-industrial rural areas and had to adjust to creating new lives in the rapidly industrializing American cities without appropriate job skills or education. And most damning of all, in the eyes of many American citizens, was the fact they were predominately Roman Catholic. At about the time, George Topp issued this set of cards, New York City had just elected its first Irish Catholic mayor and Boston was soon to follow. For Americans with a xenophobic bent, these cards sets were a welcome reminder of the lowly status of “others” in the not-so-distant past.

Sarah J. Weatherwax

Curator of Prints and Photographs