Working Upright: Standing Desks in the Eighteenth Century

Linda August, Curator of Art & Artifacts and Visual Materials Cataloger

Many of us are spending more time in our homes than ever. We are working, reading, and writing—not unlike our predecessors. They also spent a lot of time hunched over a desk. As sitting too much is unhealthy, standing desks have recently been promoted. But standing desks are not a new invention. Our 18th-century forebearers certainly knew of their benefits, and there are several surviving examples, including one in the Library Company’s collection.

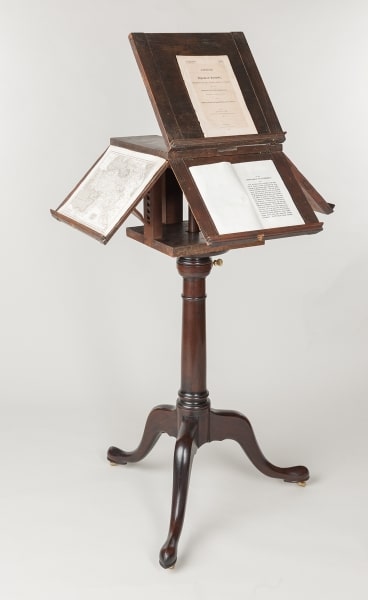

Founding father John Dickinson (1732-1808) was known as the “Penman of the Revolution” for his numerous publications supporting the American cause. But in 1756, he was still a student in London studying to become a lawyer. He had the same issue so many of us face, having health problems from being huddled over a desk all day. In a letter dated January 8, 1756 to his father, Samuel Dickinson, he wrote, “As I have great reason to believe that my disorder proceeded from my bending to write; I now read & write at a high desk at which I am obliged to stand.” Two months later he wrote to his mother, Mary Cadwalader Dickinson, “I have been advised to stand at a high desk to read & write & … though it was a little troublesome at first, yet I can now stand two hours together without any trouble; so that I do every thing on my legs, & may properly enough be called a Peripatetick Lawyer….” He returned home to America and had this Chippendale-style, mahogany reading and writing stand made. It provides multiple surfaces for books and papers. Each of the four sides has a lip along the bottom that books could rest upon. The desk can be raised or lowered by turning along the pole. A locked compartment allowed Dickinson to secure correspondence and other valuables. Underneath each corner are slots that can pull out and hold an inkwell.

Reading and Writing Stand (Philadelphia, ca. 1770s). Gift of Albanus C. Logan, 1870. Owned by John Dickinson.

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) also owned a reading stand. He was especially interested in furniture that could make his work more efficient and convenient and had several pieces made to aid with this task. He commissioned furniture from cabinetmaker Thomas Burling in 1790 shortly after he became Secretary of State. The commission included a revolving armchair and a reading stand. Both still survive at Monticello. When closed the stand looks like a wooden cube atop a pedestal. The cube, however, is composed of five adjustable wings. The five surfaces can hold letters, pamphlets, or other documents. The cube can rotate and spin. Jefferson could adjust the height by raising or lowering it. Ink stains on the top flap show that he used it as writing stand, as well. [1]

Attributed to Thomas Burling. Revolving Stand (with reproduction base) (New York, 1790). Owned by Thomas Jefferson. Images courtesy of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello.

Both of these men were prolific readers and writers. Jefferson lamented in a letter to John Adams “from sun-rise to one or two aclock, and often from dinner to dark, I am drudging at the writing table. and all this to answer letters into which neither interest nor inclination on my part enters… this is the burthen of my life, a very grievous one indeed.”[2] We can take heart when answering all of those emails that even Jefferson wearied of responding to his mail. The volume of correspondence from these men is staggering! Jefferson’s published papers number fifty-nine volumes to date, and they are still being published. John Dickinson’s papers, many of which are held in the Library Company’s collection, have just begun to be published. The University of Virginia Press issued volume one of The Complete Writings and Selected Correspondence of John Dickinson this year. As many of us may have discovered, having a comfortable work station makes an immense difference. These objects show us that it is indeed true that the more things change, the more they stay the same.

[1] Ehrenpreis, Diane. “Enlightened Networks: Thomas Jefferson’s System for Working from Home.” Paper given at The Spirit of Inquiry in the Age of Jefferson conference at the American Philosophical Society, June 7-8, 2018.

[2] Thomas Jefferson to John Adams, 11 January 1817 Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Retirement Series, 10: 657-658. Also in Founders Online, National Archives, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-10-02-0510 (accessed June, 2020).