Exploring Racism in Medicine through LCP Graphics

Kinaya Hassane

Curatorial Fellow, Graphic Arts

The disproportionate effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on non-white communities has made clear a far-longer history of racism and inequality in medicine. History tends to remember the Library Company for its role in laying the foundation for democracy in the United States. However, the institution is also implicated in the history of medical racism in the United States. Through the Imperfect History project, the curatorial team has examined materials in the Graphic Arts Collection that illustrate the role early Philadelphia physicians played in propagating racial pseudoscience and perpetuating inequalities. The presence of these objects in the collection exemplifies how institutions like the Library Company reinforced racial stereotypes by serving as a repository for this new “knowledge.”

On November 4th, 1790, the Library Company’s Board of Directors received “a print of a pyebald negro boy” from expatriate Quaker physician Thomas Pole (figure 1). The boy, John Primrose Bobey (b. 1774), was born into slavery in St. Lucia with piebaldism, a pigmentation disorder that gave his skin a spotted appearance. His condition attracted the attention of a Liverpool merchant named Mr. Blundell. Blundell arranged to exhibit Bobey throughout England at the age of twelve. Bobey subsequently achieved fame as the “Spotted Indian,” and became the subject of pictorial depictions that circulated widely throughout the Atlantic world. The hand-colored engraving that Pole gifted to the Library Company depicts Bobey holding a portrait of his younger self. Pole published the print in 1789, nearly a decade after Blundell took Bobey from the Americas to Europe. Yet, the artist imagines him in his “native” environment and dressed in a loincloth. This fictive portrayal emphasizes what viewers found most fascinating about Bobey: his Blackness and his skin condition that made him appear partially “white.” It also suggests an inherent and racialized connection between these two qualities.

Primrose: The Celebrated Piebald boy, a Native of the West Indies; Publicly [sic] Shewn in London 1789 (London: Printed and sold at [T. Pole?], No. 55 Graceh. Strt, ca. 1790). Hand-colored engraving.

Associations between Blackness and the origins of medical illnesses were common in the eighteenth century. In 1792, Library Company shareholder and physician Benjamin Rush presented a paper at the American Philosophy Society. Rush’s paper argued that leprosy caused people of African descent to have black skin. The paper even cites another case of a man with piebaldism or vitiligo: “The leprosy sometimes appears with white and black spots blended together in every part of the body. A picture of a negro man in Virginia in whom this mixture of white and black had taken place, has been happily preserved by Mr. [Charles Willson] Peale in his museum.”

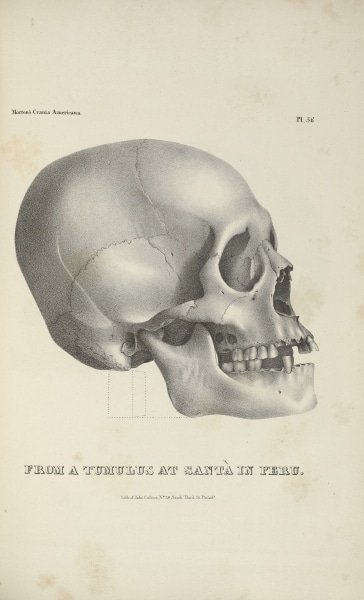

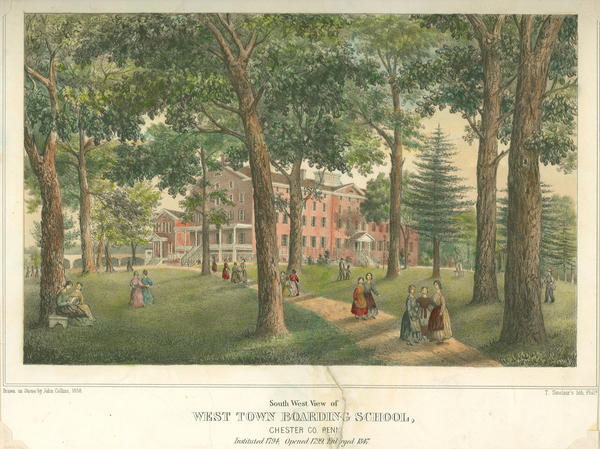

The 19th century saw the proliferation and widespread acceptance of racial pseudoscience. Philadelphia’s visual culture played an integral role in legitimizing these so-called “discoveries.” Samuel Morton, whose books and papers are housed at the Library Company, was an influential physician and co-founder of the Pennsylvania Medical College. Morton wrote Crania Americana which was published in 1839. Morton presented his findings in the text that white people had the largest skulls of any racial group and Black people had the smallest. Morton used this now-debunked research to argue in favor of white supremacy. Philadelphia lithographer John Collins created the book’s illustrations. The Graphic Arts Collection holds several other works by Collins. Most of these objects are lithographs that depict Philadelphia area landmarks such as a Quaker boarding school. Though they do not pertain to Morton’s racist theories, they exemplify the extent to which the iconographies of medical racism coexisted with more quotidian aspects of a city’s visual culture.

Pl. 56 in Samuel George Morton, Crania Americana or, A Comparative View of the Skulls of Various Aboriginal Nations of North and South America (Philadelphia: J. Dobson; 1839). Lithograph. Digital image curtoesy of Smithsonian Libraries.

John Collins, South East View of West-town Boarding School. Chester Co. Penna. (Philadelphia: T. Sinclair’s lith., 1858). Hand-colored lithograph. Westtown School Archives.

A 20th-century photograph taken by the Photo-Illustrators commercial photography firm also exemplifies persistent inequalities in medicine in the United States. The image depicts two Black women and a white woman receiving and awaiting medical treatment from several white medical professionals. The photograph provides no explicit contextual information about where it was taken. However, visual elements suggest that the setting is a community clinic. For instance, the three women are being cared for in a single room with stained floors. Much like today, community health centers in the early 20thcentury were intended to serve people who had limited access to quality medical care. As the conditions portrayed in the photograph suggest, these centers were far from a perfect solution to healthcare access disparities. To this day, non-white Americans continue to experience major obstacles to getting the medical care they need.

John Collins, South East View of West-town Boarding School. Chester Co. Penna. (Philadelphia: T. Sinclair’s lith., 1858). Hand-colored lithograph. Westtown School Archives.

These examples in the Graphic Arts Collection speak to the need for curators and audiences to reconsider our inquisitory relationship to historical objects. We tend to see objects from the past as evidence of certain historical truths. But just as we must be discerning and wary of misinformation that spreads by way of the internet, we also must be cognizant of the biases and half-truths that historical visual objects present to us.

Imperfect History is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, Walter J. Miller Trust, Center for American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Jay Robert Stiefel and Terra Foundation for American Art.

![Primrose: The Celebrated Piebald boy, a Native of the West Indies; Publicly [sic] Shewn in London 1789 (London: Printed and sold at [T. Pole?], No. 55 Graceh. Strt, ca. 1790). Hand-colored engraving. Primrose: The Celebrated Piebald boy, a Native of the West Indies; Publicly [sic] Shewn in London 1789 (London: Printed and sold at [T. Pole?], No. 55 Graceh. Strt, ca. 1790). Hand-colored engraving.](https://librarycompany.org/wp-content/uploads/JPG_digitool_128584_Primrose-404x600.jpg)

![Photo-Illustrators, [Interior of a medical clinic], ca. 1930. Gelatin silver print. Photo-Illustrators, [Interior of a medical clinic], ca. 1930. Gelatin silver print.](https://librarycompany.org/wp-content/uploads/JPG_digitool_130021_Interior-of-a-medical-clinic.jpg)