Remembering Afong Moy

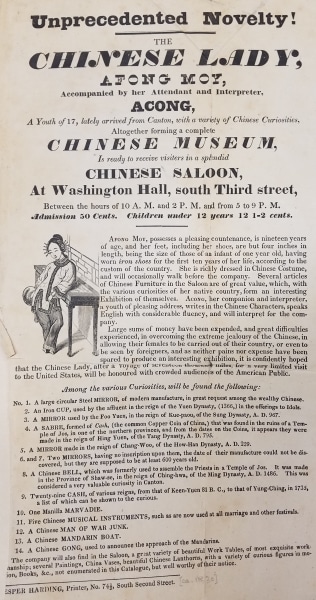

This 1835 Philadelphia broadside in the Library Company’s collection publicizes an exhibition of Chinese objects. A list of fourteen of the “various curiosities” on display is noted, including a mirror made in the reign of Chang-Woo, A.D. 229; five Chinese musical instruments; a Mandarin boat; as well as furniture, paintings, vases, and other items not enumerated. None of these items are illustrated. Instead, there is a portrait of a young, nineteen-year-old woman. She is marketed as a curiosity herself revealing a darkly racist 19th-century practice of putting human beings on display. “Unprecedented Novelty! The Chinese Lady, Afong Moy” exclaims the advertisement, which further explains the spectacle one would see in the “Chinese Saloon.” Audience members could interact with her through the seventeen-year-old interpreter Acong from Canton who was fluent in English and could write in Chinese characters. Attendees could see Afong in her “Chinese costume.” A glimpse is shown in her portrait, as a beautiful woman, her hair pinned up with decorative ornaments, wearing a tunic and pants, with lotus shoes on her feet, leaning with her elbow against a table. Her four-inch feet are emphasized, and it is indicated that she “will occasionally walk before the company.” Who was Afong Moy, and what happened to her?

Advertising broadside. The Chinese Lady, Afong Moy. Philadelphia: Jesper Harding, 1835.

Detail.

Afong Moy arrived in America in October 1834. Salem merchants Francis and Nathaniel G. Carnes, along with ship captain Benjamin Obear and his wife Augusta, brought her from Guangzhou, China. They would use her as a marketing ploy to promote the Chinese goods they were selling. To garner attention and attract customers, they created an “exhibition and salon,” using Moy to draw a crowd. The first exhibition and sales campaign with Moy presenting Chinese objects began at Obear’s house in New York City in November 1834. He erected a tableau where she was seated. Through the interpreter Acong, she discussed the objects around her to entice buyers to purchase the items for sale.

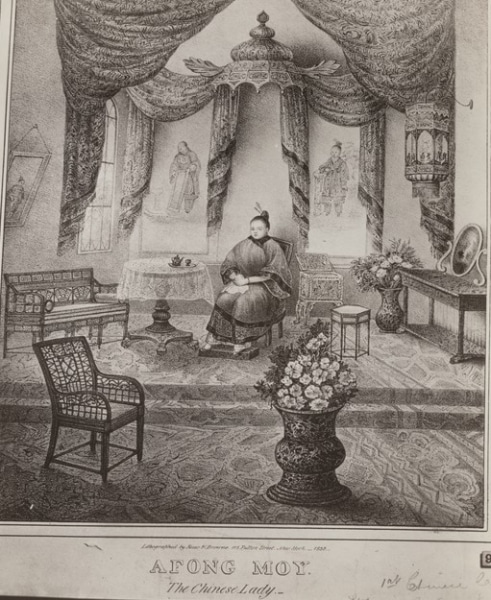

Afong Moy, the Chinese Lady. New York: Risso & Browne, 1835. Courtesy of the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Print Collection, New York Public Library.

In this lithograph created by Charles Risso and William R. Browne, Moy is shown seated in an armchair reminiscent of a throne, with a curtain behind her and surrounded by beautiful furnishings. She is attired in Chinese dress with her hair styled and pinned up with accessories. Spectators could gawk at her feet, which rest on a footstool on display. She would occasionally get up and walk around the room to further gratify the visitors’ desire for a spectacle.

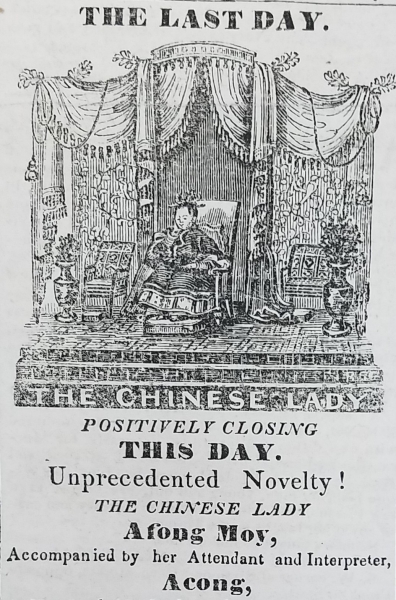

The salon would be recreated in numerous cities in a tour across America. Philadelphia was the next stop. They set up in Washington Hall on South Third Street, which contained an auditorium capable of holding 6,000 people. An advertisement in the Philadelphia newspaper, the American Sentinel, has similar text to our broadside and depicts staging like that employed in New York. But it also explicitly notes “the sale of Chinese furniture will take place on Friday the 20th of February, positively, as the Chinese Lady leaves for Washington on Saturday.” The rhetoric highlights the merchants’ aim for sales more than just an exhibit of historical objects and cultural exchange.

Advertisement in the Philadelphia newspaper the American Sentinel, February 17, 1835.

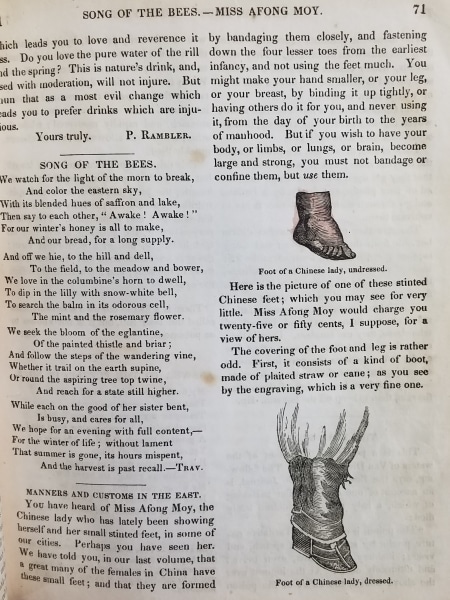

On January 27, 1835, eight Philadelphia physicians “in company of some of their friends, by invitation of the conductors of the exhibition” examined Moy’s feet to measure and certify their appearance. They signed a statement of the findings, which was published in a number of newspapers, that Moy’s feet were in fact 4 ¾ inches.[1] For Chinese women, unwrapping their bound feet and having others look and touch them, especially strange men, would have been unthinkably, egregiously offensive and publicly humiliating. Moy would not have given permission for such an act. They abused and exploited her body. Americans were fascinated by her feet. It was a main reason why people went to see her. It is mentioned consistently in every report about her, including juvenile literature. Parley’s Magazine, a children’s periodical, wrote “you have heard of Miss Afong Moy, the Chinese lady who has lately been showing herself and her small stinted feet, in some of our cities.” It illustrated her feet, both naked and in shoes. These would have been pornographic images in China regardless the source.

“Manners and Customs in the East,” Parley’s Magazine, January 1, 1835.

After Philadelphia, the group traveled to Washington, D.C., where Moy met President Andrew Jackson at the White House. (She had met Vice President Martin Van Buren in New York already.) Over the next two years, the group journeyed to Baltimore (presenting at the Peale Museum), Charleston, Boston, Albany, New Orleans, Cincinnati, Havana, Cuba, and over a dozen more cities.

Thousands of people came to see her. And thousands more read about her in newspaper articles, periodicals, and books. Newspapers wrote about and publicized the event as they traveled. A search in the newspaper database GenealogyBank for “Afong Moy” results in 393 articles from twenty different states!

The influence of Asian culture (and Moy) in America is evident in household furnishings, decorative objects, crafts, hairstyles, and clothing. Godey’s Magazine is permeated with Asian references and goods. The pages are filled with instructions for leisure activities, like Chinese watercolor painting and using rice paper for various crafts. “Shawls are indispensable” according to the fashion magazines.[2] Extremely popular, Chinese silk shawls appear in numerous fashion plates, as do fans, another fashionable accessory. Large quantities of both were imported and sold. American women copied Chinese hairstyles, with descriptions of the latest trends as, “the hair is dressed in the Chinese fashion.”[3] In a short story, one of the characters strikingly remarks “with all my hair stroked back from my forehead, and knotted at the top of my head, I shall look like Afong Moy.”[4]

Godey’s Lady’s Book. Vol. 1, no. 4, October, 1830. “Large scarlet shawl of embroidered Canton crape.”

Godey’s Lady’s Book. Vol. 4, no. 1, January, 1832. “Black Canton crape shawl, embroidered with Flowers in bright colours.”

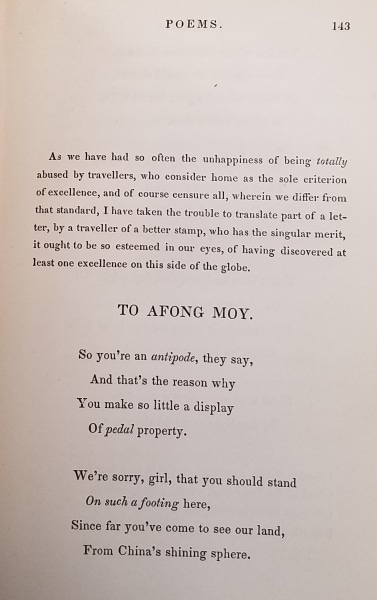

Many Americans wrote about their unease regarding Moy’s exploitation including John Kearsley Mitchell, a medical doctor who had previously traveled to China as a ship’s surgeon. In a poem he wrote in 1835, which was published in newspapers and later in his book, he seemed to have an awareness of the egregiousness of how Afong was treated. He questioned whether she would have departed her home had she known what would be done to her: “Didst thou suppose thy tiny feet, by day-light could be shown?” The editor of the New York Mirror opinioned that, “we have not been to see Miss Afong Moy, the Chinese lady with the little feet; nor do we intend to… to convert a lady into an exhibition is by no means to our taste.”[5]

John Kearsley Mitchell. Indecision: A Tale of the Far West and Other Poems. Philadelphia: E.L. Carey & A. Hart, 1839.

We have no direct record of Afong’s thoughts or feelings, but she must have been extremely homesick and exhausted and felt exposed. In Charleston, another set of doctors examined her feet yet again. This time her naked feet would be bared publicly to the audience, as well. The Southern Patriot reads, “it is with considerable difficulty she has been persuaded to expose the naked foot, being in direct opposition to the delicate customs of her country.”[6] Most of these physicians were enslavers, who would not give her the freedom of refusal. Moy was supposed to return home to China after one year. Captain Obear left for Guanzhou in the Spring of 1835 and several times thereafter but did not take her. From at least May 1835, Henry Hannington of New York was her manager. He had a business producing dioramas in the city. The exact transaction of this indenture from the Carnes and Obear to Hannington is not known. Moy would become less of a marketing tool for selling Chinese goods and instead became the performance, spectacle, and commodity onstage. The interpreter Acong’s name also disappeared from advertisements. Newspaper articles note that Moy was able to converse in English from at least July 1835. Whether Acong left of his own volition or Hannington did not want or need to manage him for this act is unknown. Hannington, as well as his wife Catherine, managed the content of the presentation completely. Moy was now paired with other acts, such as a ventriloquist and magician.

When the Panic of 1837 occurred, the financial collapse resulted in people having less money to spend on entertainment. Those who profited off of Moy totally abandoned and deserted her. She had no support and no way to return home. In March 1838, the Monmouth Inquirer published articles locating Afong in Monmouth County, New Jersey. She was living with an indigent widow and her family. In the articles, Afong confirmed that she was brought to America with the promise of a one-year stay. “After her agent ‘could no longer attract the attention of the public, she was brought to this county, and placed under the direction of a widow woman of very indigent circumstances who … is wholly unable to administer to the comforts, and every day wants of her guest.”’ “She [Moy] appears to be much dissatisfied with her present situation and mode of living—her personal treatment we strongly suspect, is not of the most pleasant kind.”[7] The story was picked up by other newspapers who criticized those who abandoned her. “The profits [for her manager] began to decrease and she was finally shamelessly abandoned in Monmouth county in this state, in a helpless situation. She was provided for by the authorities of the county in their poor-house—where she remained…when a company of persons redeemed her, by defraying the expenses of her maintenance.”[8] After the public outcry, Henry Hannington began to contribute $2.50 a week to the family that boarded her.[9] She remained in Monmouth for another eight years. Then, P.T Barnum must have become acquainted with Moy from Hannington through his work as a painter of signs and decorative paintings for dioramas. Barnum became her manager and once again objectified her before audiences. Beginning in July 1847 at Niblo’s in New York, she began more years of touring. Moy and Charles Stratton, also called General Tom Thumb, periodically presented together onstage for two years. Spectators would watch her sing a song in Chinese and eat with chopsticks. After 1851, there are no more known written accounts about Moy. She has not been found in census or death records. Did she end up in another poorhouse? When did she die? Barnum, notorious for exploiting people, does not seem to have provided any support. It is unlikely that she returned to China.

Though Afong Moy’s thoughts and emotions have to be deduced from sources, mostly observations written by others, parts of her story are clear. She was a survivor. She was not ashamed of who she was and was proud of her heritage and culture. Her name is remembered, written about, and honored almost two centuries later.

Linda Kimiko August, Curator of Art & Artifacts & Visual Materials Cataloger

[1] “Novel Examination,” American Sentinel, February 2, 1835.

[2] Godey’s Lady’s Book. Vol. 19, no. 4, October, 1839.

[3] Godey’s Lady’s Book. Vol. 1, no. 5, November, 1830.

[4] “Althea Vernon, or the Embroidered Handkerchief,” Godey’s Lady’s Book. Vol. 16, no. 4, April, 1838.

[5] New-York Mirror, Vol. 12, no. 23. December 6, 1834.

[6] Southern Patriot, May 1, 1835.

[7] Monmouth Inquirer, March 21, 1838 as seen in Davis, Nancy E. The Chinese Lady: Afong Moy in Early America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019, p. 229-230.