Women Get Things Done during COVID

Cornelia King, Chief of Reference and Curator of Women’s History

For Library Company staff, COVID has brought opportunities as well as challenges. With the gallery closed to visitors and the reading rooms empty, we have had time to tackle new projects. Last spring, for example, I assisted Director Emeritus John C. Van Horne in his retirement project on naturalist and collector Pierre Eugène Du Simitière. For this work, I sought to identify the pamphlets that the Library Company purchased at the Du Simitière sale on March 10, 1785. (If you search “wpa simitiere,” you can locate the 595 records I updated in our online catalog WolfPAC.)

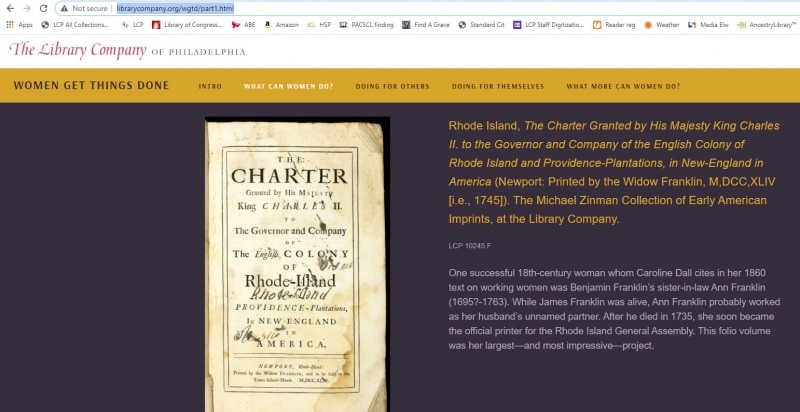

In the course of that work, I discovered items that had been printed by women – or sold by women in their bookshops. We have long tagged records with local headings such as “Women printers” and “Women booksellers” when we catalog, and Americanists will recognize names such as Ann Franklin, who was Benjamin Franklin’s sister-in-law. After her printer-husband James Franklin died in 1735, she continued in the printing business. One of her books is featured in the first section of our Women Get Things Done exhibition. And the record in WolfPAC is tagged “Women printers” accordingly:

So I was surprised to “discover” so many “un-tagged” women printers and booksellers. For example, Pierre Du Simitière owned a copy of the printed version of General Monck’s speech of February 21, 1659/1660, which was printed by “S. Griffin.” It turns out “S. Griffin” was Sarah Griffin, the widow of London printer Edward Griffin, who died in 1652. Like Ann Franklin, Sarah Griffin continued the family business following her husband’s death.

For our large collection, we of necessity rely on legacy data, and consequently there are many cataloging records that have not been upgraded to current standards. After I completed the first stage of the Du Simitière project for John Van Horne, I started thinking about ways to locate more “hidden women” who were printers, booksellers, or publishers. First, I started improving or replacing the records for 17th- and 18th-century French-language items with women booksellers or printers identified in the imprint as “veuve” (i.e., widow), after seeing many French-language items with “veuve” in their imprints in the Du Simitière material. After that, I looked for the words “widow” in English and various other European languages in the imprint field: vidua/vidua/viduam (Latin), vedova (Italian), Witwe/Wittwe (German), weduwe (Dutch), and viuda (Spanish).

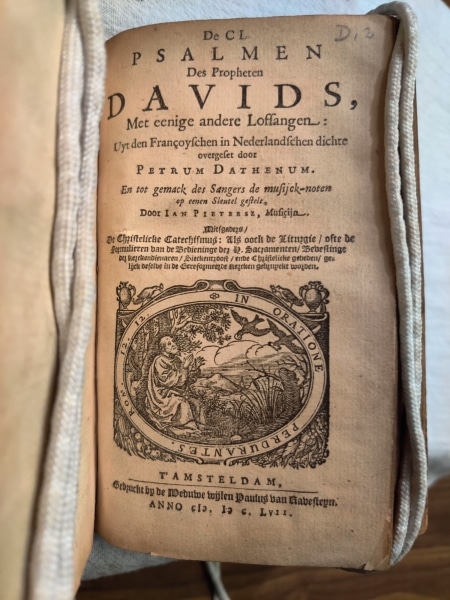

And many of these works were significantly ambitious, such as Elisabeth Sweerts’s 1657 Dutch Bible and the accompanying Psalms of David (of which the title page is shown here):

The imprint reads: T’Amsteldam : Gedruckt by de weduwe wijlen Paulus van Ravesteyn, anno 1657. We know that Elisabeth Sweerts was the widow of Paulus Aertsz van Ravesteyn, and continued the family business after he died in 1655.

Others include:

- Madrid printer Maria Ruiz (active 1584-1595), the widow of Alonso Gomez

- Antwerp printer Jeanne Rivière (d. 1596), the widow of Christophe Plantin

- Antwerp printer Martina Plantin (1550-1616), the widow of Jan Moretus

- Toulouse printer Marguerite de Molinier, the widow of Jacques Colomiès (active 1569-1593), who was also the daughter of printer Nicolas d’Estey.

- Frankfurt printer Esther Rosa (active 1619-1672), the widow of Jonas Rosa

- Paris printer Jeanne Burée (active 1629-1652), the widow of Charles Boscard

And many, many others. There are currently 701 records in WolfPAC, representing books that women printed either on their own or in partnership with other people – representing decades of cataloging plus the many I’ve tagged only recently.

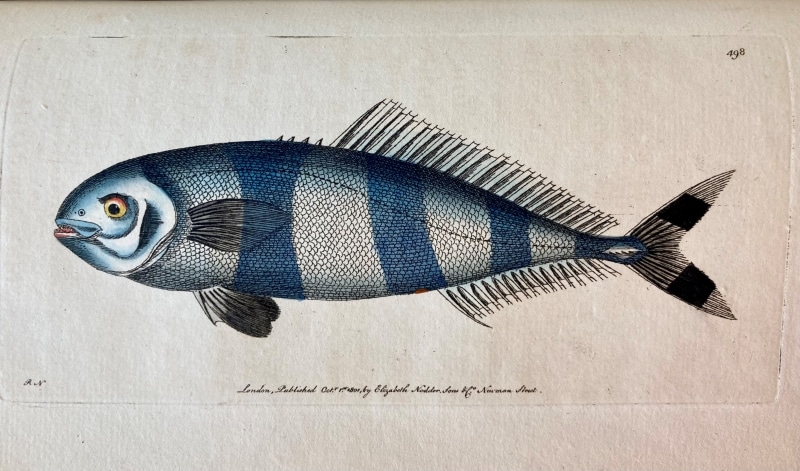

And I keep finding more, often with help from other staff. Earlier this month, Conservator Alice Austin noted that George Shaw’s Vivarium Naturae, or, The Naturalist’s Miscellany (London, 1790-1813) was issued – in part – by Elizabeth Nodder. Her artist-husband Frederick Polydore Nodder began the multi-volume work, but died in either 1800 or 1801. Starting with volume 13, Elizabeth and her sons continued issuing volumes, and she even produced an index as a twenty-fifth volume for the set. The Naturalist’s Miscellany contains hand-colored plates of extraordinary beauty, some of which Alice Austin showed with her blog post about Elizabeth Nodder continuing the family business following the death of her husband.

Do check out Alice Austin’s blog post, showcasing Elizabeth Nodder and the beautiful volumes she helped produce! https://librarycompany.org/2021/03/04/elizabeth-nodder-and-the-naturalists-miscellany/

And the work continues; please contact me if you find records in our online catalog that still need to be tagged!

Pilot Mackerel from The Naturalist’s Miscellany printed by Elizabeth Nodder