(Im)perfect Pages

Kinaya Hassane

Curatorial Fellow, Graphic Arts

One part of my fellowship at the Library Company that I was not expecting was the messiness of working in special collections. When we receive a large collection of items from a member of the public, the objects often come to us in a state of disarray. While getting these gifts is daunting, it is nonetheless exciting to know that a family or community member trusts me and my colleagues to take care of and interpret their valued photographs, prints, or watercolors.

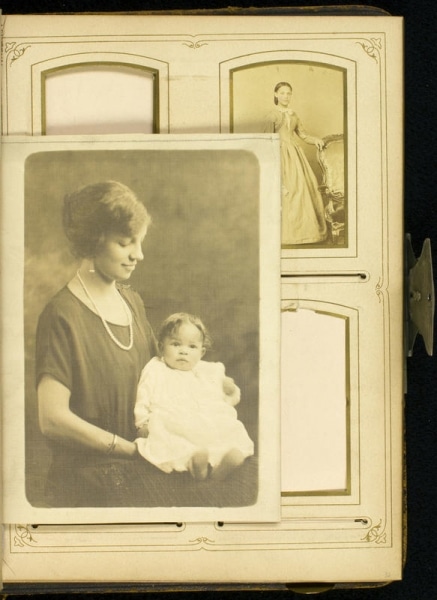

What is even more intriguing, however, is encounter works in our collection which have already been processed but still embody this messy imperfection. The Stevens-Cogdell/Sanders-Venning Family Album is an example of one such object. As you flip through the pages, the album’s visual and physical quirks become immediately evident. There are pages with photographs on top of one another. Other pages do not have any images at all. The pages with multiple photographs have images from different time periods, with photographs from the 20th century overlapping those from the 19th century. There are duplicate portraits throughout the album. The portraits represent a wide range of mediums with silhouettes, cabinet cards, tintypes, and cartes de visite mixed among one another.

Portrait photograph of Louise Sanders Venning inserted before page 32 of Stevens-Cogdell/Sanders-Venning Family Photograph Album, ca. 1860-1925.

These imperfections work together to create a vivid picture of the life of this multi-generational, middle-class African American family. In a lot of ways, it reminds me of my own family albums, which contain all kinds of oddities, including a silhouette my parents had me sit for when I was an infant. Being able to associate myself and my family’s memories with an object that is held in America’s oldest cultural institution is an important sign of the Library’s ability to tell a more inclusive story of the nation’s history.

Portrait photograph of Cordelia Chew Hinkson and her daughter Cordelia Hinkson Brown inserted before page 32 of Stevens-Cogdell/Sanders-Venning Family Photograph Album, ca. 1860-1925.

At the same time, it is worth interrogating how this album actually continues to tell an incomplete story, given its focus on a middle-class Black family. Over the Library Company’s history, tellingly, acquisitions of graphic materials with degrading and dehumanizing depictions of Black people predominated. The gift of the Stevens-Cogdell/Sanders-Venning Album is formative for the Library. However, while the volume represents a more dignified picture of African American families, the life represented and its comforts were reserved for those who were able to rise in social status.

As we continue to think critically about past curators’ collecting priorities and adjust those of the present day priorities accordingly, it is imperative to keep considering how Black people are under and misrepresented in our collection. It is also just as important for us to think of identity in an intersectional manner so we can acknowledge the perspectives of those who are often left out if we think solely in terms of race and ethnicity.

Imperfect History is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, Walter J. Miller Trust, Center for American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Jay Robert Stiefel and Terra Foundation for American Art.