A Philadelphia Photographer’s Visions of Race and Empire

In the 1981 Library Company of Philadelphia Annual Report, it was noted that the Print Department had made a significant acquisition of works by 19th-century Philadelphia photographer, William Jennings (1860-1946). The gift, which included 652 lantern slides, was donated to the Library Company by Jennings’s son Ralph. When describing the gift, the report focused on William Jennings’s interest in scientific and urban photography. Although a significant portion of the lantern slides were taken in Cuba and the British West Indies, the series was mentioned only in passing when discussing Jennings’s penchant for street photography. Re-examining these photographs gives us the opportunity to critically examine Jennings’s participation in essentialist and colonial modes of representing the Black subjects in his photographs.

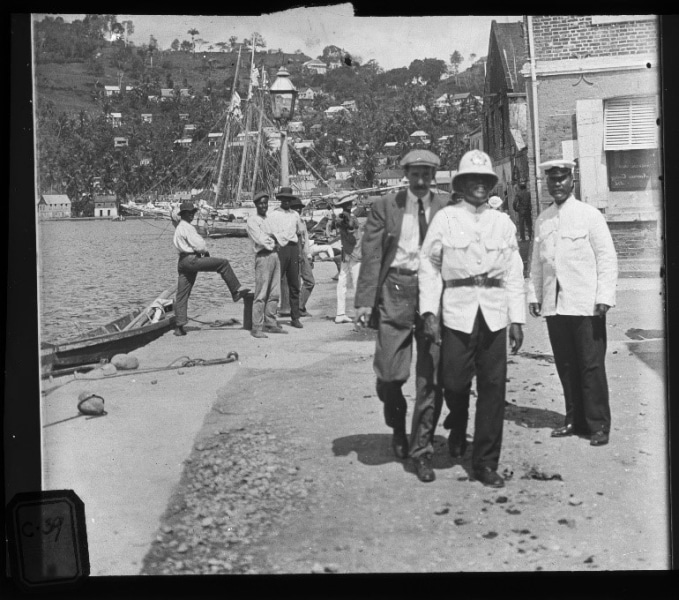

William Jennings, Barbados Policemen and Stokes, ca. 1920. Lantern slide.

Likely taken in the 1920s, this series of about 140 lantern slides depict the tropical landscape and individuals Jennings encountered during his travels through the Caribbean. The images’ medium is worth noting since lantern slides were meant to be projected. Given Jennings’s active participation in local Philadelphia photographic clubs and societies, it seems probable that he had taken these photographs to present to his peers.

Though the lantern slides’ presentation for recreational purposes seems innocuous, it is important to consider the medium of photography as a whole and the role it has played in justifying slavery and colonialism. Ever since its inception, photography was employed by white photographers, in collaboration with scientists and anthropologists, to reinforce notions of racial difference in the United States and abroad. In 1850, biologist Louis Agassiz (1807-1873) commissioned photographer Joseph T. Zealy (1812-1893) to create a series of daguerreotype portraits depicting enslaved Africans and their American-born children in South Carolina. Agassiz hoped that by commissioning these now-notorious photographs, he would have concrete evidence with which he could prove the inferiority of “the African race.”

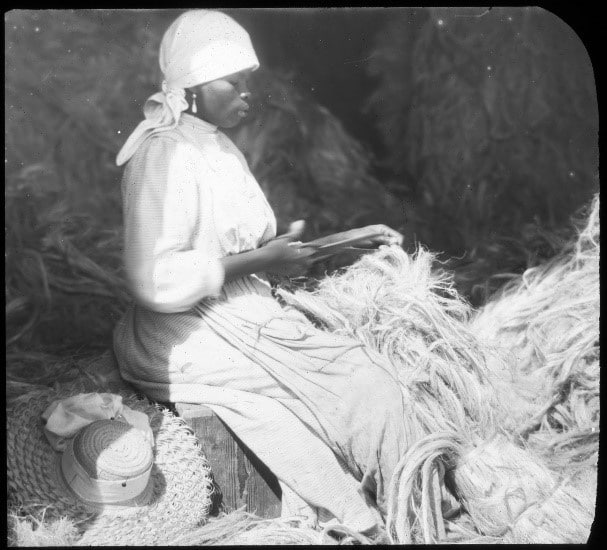

William Jennings, Barbadoes Pottery, ca. 1920. Lantern slide.

Jennings’s photographs of daily life in places like Jamaica and Barbados do not carry the same overtly violent and racist connotations as those taken by Zealy. Many of the subjects in these lantern slides are depicted performing various kinds of labor. While these images could be viewed as typical genre scenes, Jennings’s choice to focus on Black subjects in the context of labor reinforces the capitalistic and extractive relationship the United States and Europe had with the Caribbean’s large Black populations since the first Africans were kidnapped and brought to the Americas. So long as Afro-Caribbean populations continued to be valued solely for their ability to produce and export agricultural goods to colonial powers, those powers could justify dehumanizing and racist colonial systems.

William Jennings, Jamaican Belle, ca. 1920. Lantern slide.

It is important to understand Jennings and his photographic practice through the lens of the colonialist and racist discourses of the era in which he lived. While the former Library Company curators and other sources tended to view Jennings as a scientific innovator, we cannot lose sight of how science and emerging technologies like photography worked to prop up the United States’ and European nations’ imperial projects.

Kinaya Hassane, Curatorial Fellow, Graphic Arts, 2019-2021

Imperfect History is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, Walter J. Miller Trust, Center for American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Jay Robert Stiefel and Terra Foundation for American Art.