Sadakichi Hartmann in the Library Company of Philadelphia

Linda Kimiko August, Curator of Art & Artifacts & Visual Materials Cataloger

Sadakichi Hartmann (1867-1944) developed a close relationship with the Library Company that emanated from several influential years spent in Philadelphia as a young man. This crucial time fueled his creativity and helped foster his development as an art critic, playwright, and poet. He entrusted the Library as a repository for his manuscripts and publications. His memories of time spent here compelled him to give these gifts over many years.

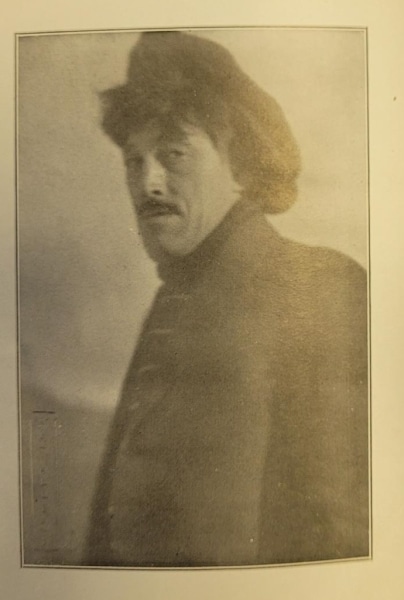

Portrait of Sadakichi Hartmann, frontispiece from Sadakichi Hartmann. My Rubaiyat. St. Louis: Mangan Printing Co., 1913. Library Company of Philadelphia.

Born Carl Sadakichi Hartmann in Japan to a German father and a Japanese mother, who died soon after his birth, he and his older brother Taru grew up in Germany. In 1881, his father sent him to the naval academy. Rebelling, he skipped school and ran away. His father then sent the fifteen-year-old Sadakichi to live with a relative in America. He spent three formative years in Philadelphia, from June 1882 to February 1885, arriving at 806 Buttonwood Street to live with his paternal grand-uncle and wife, an older, childless couple. The city of Philadelphia became the perfect place for Sadakichi to pursue his passion for literature and the arts. In an unpublished autobiography, he recalled those early years. “Within a week my uncle had found a job for me at a lithographic printing house that made a specialty of labels and borders for cigar boxes.” [1] As the youngest apprentice he cleaned, moved packages on a handcart, and pinned the sheets for the cutting machine. He earned three dollars a week, two of which had to be handed over to his uncle. The firm went bankrupt around New Year 1883. He found a job at Wells & Hope, who specialized in lithographic tin signs and worked once again as the youngest apprentice. A series of jobs followed. He worked for an independent lithographer, a tombstone designer, and he eventually earned nine dollars a week as a stippler. He quit to try his hand in photography as a negative retoucher for which he lacked skill and subsequently was fired from several employers.

He continued his education while in Philadelphia attending evening school to work on his English. He recalled that his fellow classmates, “… were all mongrel American boys who tried to tease me during lessons….” After a fistfight, he stopped attending. He then enrolled in drawing classes at the Spring Garden Institute, where they drew from casts. He was awarded second prize for a copy in charcoal of the bust of Aretino. His work with lithography companies inspired him to continue drawing. “I drew at all available time, copied from photographs, designs, magazine illustrations in pencil, crayon, charcoal, pen and ink (not yet in pastel, my favorite medium).” His new interest in acting prompted him to take elocution lessons. “…I struggled for clearer articulation, only I used a spoon instead of pebble stones for exercise. I made wonderful progress and at one time spoke English almost without an accent, but afterwards fell back into my German accent and never entirely overcame it.”

Hartmann took advantage of Philadelphia’s many cultural institutions, which were critical in contributing to his passion for the arts and his motivation to be educated. “I made frequent visits to the Pennsylvania Academy of [the] Fine Arts (with orchestral music as it should be certain afternoons every week) and admired Eakins’ Crucifixion, and some of Schuessell’s and Kirckpatricke’s work…and a canvas of some Italian painter depicting the murder of a Parisian woman in the Piloty style.” He also attended the theater, “being stagestruck.” He became “despairing in love with the stage” and bought tickets for as many performances as he could afford.

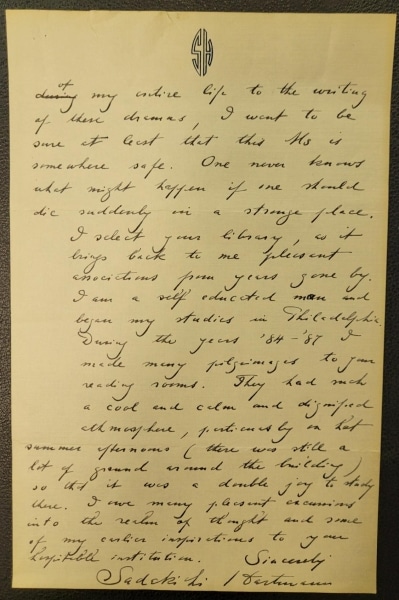

As a voracious reader with little money, he frequented the city’s libraries and second-hand bookstores. He purchased on credit a “wagonload of books in German, the complete works of Goethe, Schiller, Lessing, Heine, Lenau, Kleist, etc. some hundred volumes….I now read instead of drawing in the early mornings.” His uncle and aunt disapproved of the time and money he spent in these interests, so he moved out to a rented room at Ninth and Poplar Streets. A week later his uncle passed away. Sadakichi decided to stop working and pursue his self-education. He lived on the meager three dollars a week his grandmother in Germany sent him. “…I desired to acquire a general knowledge of literature, in particular of the drama. I was also eager to know everything that has something to do with the fine arts… music, dancing, Delsarte and mimicry, history and the history of costume, theatres, biographies of actors, anthropometry artistic anatomy, foreign literature, etc. Whatever the Mercantile Library contained on these topics I tackled….The library had open shelves, so I could go to any department and indulge in the orgy of taking out a dozen books or more at one time.” The importance that the Library Company had on him is evident in our surviving correspondence. In a letter to Librarian George Maurice Abbot, he wrote, “I am a self educated man and began my studies in Philadelphia. During the years ’84 –’87 I made many pilgrimages to your reading rooms. They had much a cool and calm and dignified atmosphere, particularly on hot summer afternoons (there was still a lot of ground around the building) so that it was a double joy to study there. I owe many pleasant excursions into the realm of thought and some of my early inspirations to your reputable institution.”[2] He later wrote in 1935 to Librarian David C. Knoblauch “…I was almost a daily guest at your library in 1884-85 trying as a 16 year old boy to mend what had been neglected in my education.”[3]

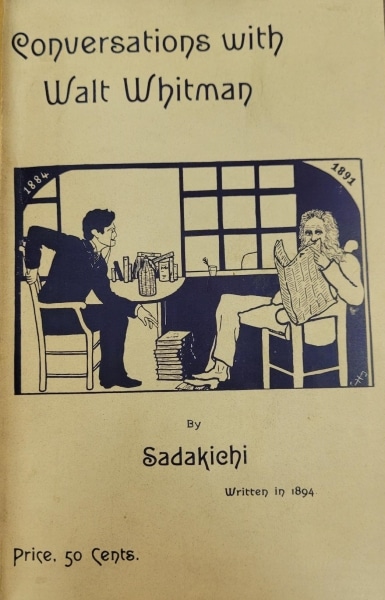

With persistent purchases, he became well acquainted with the owner of a second-hand bookstore through whom he was able to meet a writer he greatly admired. “…The dusty bookseller advised me to call on Walt Whitman. ‘He is living right across the river, in Camden, he likes to see all sorts of people.’”[4] Hartmann’s visits culminated in a book published in 1895 several years after the poet’s death. Conversations with Walt Whitman begins with his first visit in November, 1884. His account provides much to examine about race and sexuality. Sadakichi wrote that Whitman immediately asked, “and you are a Japanese boy, are you not?” Hartmann talked about his love of the stage and desire to be an actor to which Whitman shaking his head replied, “I fear that won’t go. There are so many traits, characteristics, Americanisms, inborn with us, which you would never get at. One can do a great deal of propping. After all one can’t grow roses on a peach tree.”[5] Did Whitman allow Hartmann to converse with him out of curiosity? This was the height of the fetishization of Japanese culture, also known as japonisme. Whitman had previously written a poem about the Japanese embassy’s opening in New York. First published by the New York Times in 1860, it was revised and added to later editions of Leaves of Grass. In “A Broadway Pageant,” he describes the “tann’d Japannee” and other Asians including the “Hindoo,” “Mandarin,” and Malaysians marching in a pageant. Ultimately, Whitman was promoting American imperialism, “I chant the new empire, grander than any before — As in a vision it comes to me; I chant America, the Mistress — I chant a greater supremacy.”[6] Whitman told Sadakichi that as a Japanese man it would not be possible for him to be able to act on an American stage.

Hartmann’s diligence in reading proved fruitful as he was able to talk widely to Whitman about authors and books. He was welcomed back many times. Sadakichi also candidly and directly asked about Whitman’s romantic relationships. “I launched upon a still more impertinent topic, on his relation to women.” Whitman “evading the question” replied “one cannot say much about women. The best ones study Greek or criticize Browning—they are no women.” Sadakichi, “rather brusquely” followed with “have you ever been in love?” to which Whitman “rather annoyed with my cross examining” answered “sensuality I have done with. I have thrown it out, but it is natural, even a necessity.” Once he asked to kiss Whitman when he left his house. “I touched his forehead with my lips. ‘Thanks, thanks!’ ejaculated Whitman. With a blush of false shame I offered him this tender tribute of youthful ardor, ambition, enthusiasm with which my soul was overflowing; I felt I had to show this man some emotional sign of the love, I bore his works or those of any remarkable individuality.”[7] Many years later in 1927, Hartmann wrote about it once again. “Of his relations with women in earlier periods of his life little is known… It was impossible to make him talk on the subject. He would evade all queries (and I tried hard enough) with a final, ‘Well, I will tell you some day.’ But that day never came.”[8] Whitman had an immense impact on Sadakichi, who referred to the author in his writings throughout his lifetime.

Sadakichi Hartmann. Conversations with Walt Whitman. New York: E.P. Colby & Co.,1895. Library Company of Philadelphia.

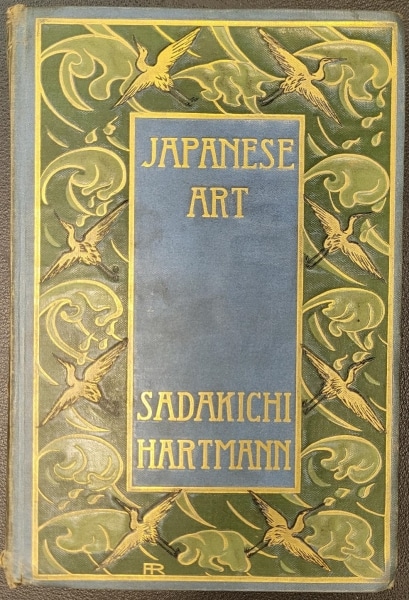

Hartmann continued writing and publishing articles, plays, and books. In addition to being well-read, his background as German, Japanese, and American made him well-suited as an art critic, most notably his published work on American art, Japanese art, and photography. History of American Art, a two-volume work published in 1902, not only covers the classical and European influence on American art but also the Japanese influence. Japanese Art, published in 1904, explores the Japanese aesthetic both visually and through poetry. Japanese Rhythms: Tanka, Haikai, and Dodoitsu Form explains these forms of Japanese poetry alongside examples of his original poems, and contains a facsimile manuscript page showing the process by which he worked including word choices and rhythms. The bindings also provided another way for him to highlight the Japanese aesthetic. The play, Confucius: A Drama in Two Acts, has the philosopher meditating on topics, such as fame, art, the government, and family. Perhaps reflecting on his own experiences, in the play a group called the “Have nothings” state, “all persons…should have equal opportunities of education, so that all dormant faculties may have a chance to be developed. I myself might have been a philosopher, alas, the avenues of knowledge were never opened to me!” Access to education and art was a reoccurring theme in Sadakichi’s writing.

Sadakichi Hartmann. Japanese Art. Boston: L.C. Page & Co., 1904. ; Confucius: A Drama in Two Acts. Los Angeles: Privately printed, 1923. Library Company of Philadelphia.

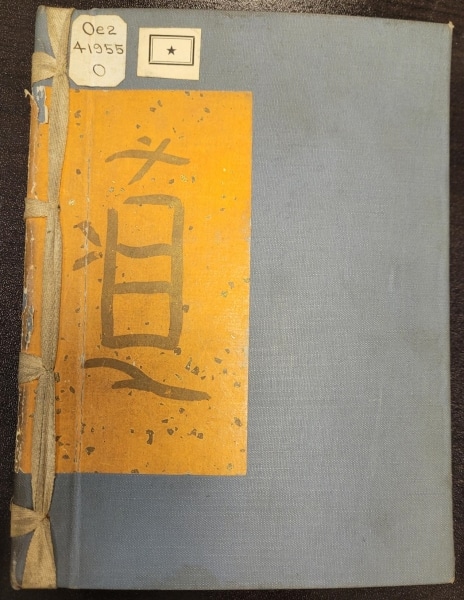

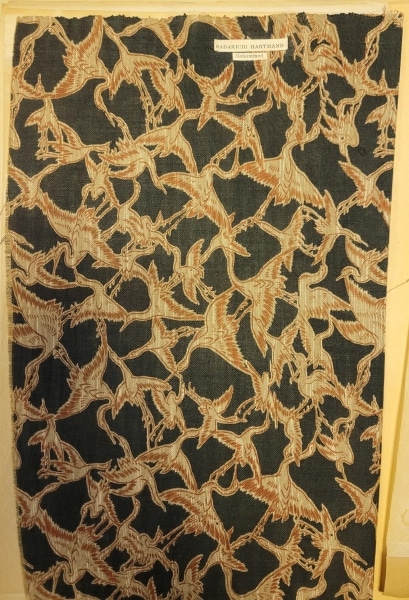

Sadakichi donated a number of his publications and original manuscripts to the Library Company over the course of many years while living in California. The impact that the Library had on him was enduring, and he remained connected even though he did not visit the institution in his later years. “My last visit was in 1915 or ’14…”[9] The first donated manuscript, the drama Mohammed, arrived in 1924 “under special cover” of a crane covered cloth.[10] He explained his motivation for choosing to have the Library Company as a repository for his work, “I am now very much of a chronic invalid…I will nigh despair of ever being able to attend to the publication of “Mohammed.” As I have devoted nearly one third of the leisure hours of my entire life to the writing of these dramas, I want to be sure at least that this Ms [manuscript] is somewhere safe… I select your library, as it brings back to me pleasant associations from years gone by.”[11] More manuscripts came to be entrusted in the Library’s care, including the play Confucius in 1930 and Moses, My Crucifixion, and Esthetic Verities in 1935. Here, they became publicly accessible. Librarian Austin Gray noted that “there has been considerable interest in the MS of Esthetic Verities. We have placed it on view with bound copies of your other works. Several people have been asking to be allowed to read the manuscript. So soon as I can, I am going to have it re-typed.”[12] Numerous published works came causing Gray to respond that, “I believe that we have one of the best collections of your publications.”[13]

Cloth cover for Sadakichi Hartmann’s manuscript copy of Mohammed, 1924. Library Company of Philadelphia.

Sadakichi Hartmann to George Maurice Abbot, April 30, 1924. Letter. Library Company of Philadelphia.

Again, Hartmann echoed his appreciation for the Library Company by donating Esthetic Verities to the institution “…where I made my first studies towards a knowledge of art and had my first visions – dreams that can not come true in a period of economic disorder and mechanization of human activities.”[14] He believed this manuscript, “represents the most monumental thing I have done.”[15] Started in 1927 and completed in 1935, this ambitious work of seventeen chapters is a “review of the evolution of esthetic thought pertaining to all arts through the ages…from Assyrian murals to modern motion color experiments.”[16]

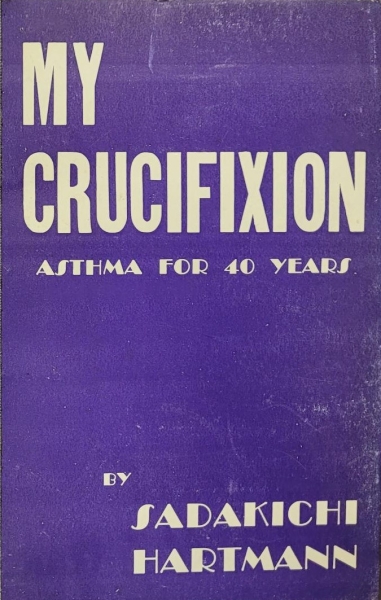

Sadakichi Hartmann endured hardships particularly in the final chapter of his life. My Crucifixion: Asthma for 40 Years details his long affliction with a chronic ailment, mentioned in his earlier letter. It takes on increased sympathies in our time of COVID-19. His childhood asthma became exacerbated after he was stricken with the Spanish flu in 1918.”[17] He detailed the real physical pain and the consequences it had on his ability to be active. He suffered a severe injury in a head-on car collision, putting him in the hospital for two months in 1936. He always struggled to earn a living as a writer and artist. He contended with racism his whole life. He became a naturalized American citizen in 1894. Despite his citizenship, during the Second World War he faced harassment and accusations because of his heritage. In 1942, the United States government forcibly imprisoned people of Japanese descent into internment camps. Sadakichi Hartmann and his family were regularly visited and questioned by the F.B.I. Approximately two-thirds of the 120,000 internees were likewise American citizens. Likely due to his age and severely poor health, Sadakichi managed to escape being sent to the camps. Nonetheless, he was investigated and needed to defend his Americanness and that he was not a spy. He died in 1944 while visiting his daughter in Florida before the war ended.

Sadakichi Hartmann. My Crucifixion: Asthma for 40 Years. Tujunga, California: Cloister Press of Hollywood, 1931. Library Company of Philadelphia.

As a similarly mixed-race Japanese person, his achievements and determination have been an inspiration to me. He had to navigate multiple identities and other people’s ideas, fascinations, and prejudices about him. He asserted his dignity and promoted and elevated Japanese art forms beyond mere imitation or curiosity. The Library Company has twelve of his publications. It is unfortunate that the Library sold two of his publications in the 1960s.[18] In the collection are additional manuscripts, including 1000 Happy Moments in a Lifetime, Baker Eddy: A Drama in Three Acts, and Boston Lions: A Comedy in Four Scenes. These works showcase the necessity of representation and acknowledging Asian American accomplishments and contributions to American history. He deserves to be more widely acclaimed and known, and there is much to research and study from his life and body of work. My hope is that more people discover the rich source material available at the Library Company.

[Raymond] Brossard. [Portrait of Sadakichi Hartmann.] Pen and ink. Library Company of Philadelphia. Yi 7430.F.2 with manuscript of Moses.

[1] Three Years in Philadelphia. Sadakichi Hartmann Papers. UC Riverside Special Collections and Archives. MS 068. Quotes taken from this source unless otherwise noted.

[2] Hartmann, Sadakichi. Sadakichi Hartmann to George Maurice Abbot, April 30, 1924. Letter. Library Company of Philadelphia.

[3] Hartmann, Sadakichi. Sadakichi Hartmann to David C. Knoblauch, Feb. 18, 1935. Letter. Library Company of Philadelphia.

[4] Sadakichi Hartmann, Conversations with Walt Whitman (New York: E.P. Colby & Co., 1895), p. 5.

[5] Hartmann, Conversations, p. 8.

[6] Whitman, Walt, “A Broadway Pageant,” in Leaves of Grass (Washington, D.C.: s.n., 1871), p. 243-7.

[7] Hartmann, Conversations, p. 26, 30.

[8] Hartmann, Sadakichi, “Salut au Monde: A Friend Remembers Whitman,” Southwest Review 12, no. 4 (July 1927): 266.

[9] Hartmann, Sadakichi. Sadakichi Hartmann to David C. Knoblauch, March 26, 1935. Letter. Library Company of Philadelphia.

[10] Hartmann, Sadakichi. Sadakichi Hartmann to George Maurice Abbot, April 30, 1924. Letter. Library Company of Philadelphia.

[11] Hartmann, Sadakichi. Sadakichi Hartmann to George Maurice Abbot, April 30, 1924. Letter. Library Company of Philadelphia.

[12] Gray, Austin. Austin Gray to Sadakichi Hartmann, March 30, 1936. Letter. Library Company of Philadelphia.

[13] Gray, Austin. Austin Gray to Sadakichi Hartmann, March 12, 1936. Letter. Library Company of Philadelphia.

[14] Hartmann, Sadakichi. Sadakichi Hartmann to the Library Company of Philadelphia, March, 1936. Letter. Library Company of Philadelphia.

[15] Hartmann, Sadakichi. Sadakichi Hartmann to Austin Gray, July 13, 1935. Letter. Library Company of Philadelphia.

[16] Hartmann, Sadakichi. Sadakichi Hartmann to the Library Company of Philadelphia, March, 1936. Letter. Library Company of Philadelphia.

[17] Sadakichi Hartmann, My Crucifixion: Asthma for 40 Years (Tujunga, California: Cloister Press of Hollywood, 1931), p. 54.

[18] The two books sold were The Last Thirty Days of Christ. New York: Privately printed, 1920 and Buddha: A Drama in Twelve Scenes. New York: Author’s edition, 1897.

![[Raymond] Brossard. [Portrait of Sadakichi Hartmann.] Pen and ink. Library Company of Philadelphia. Yi 7430.F.2 with manuscript of Moses.](https://librarycompany.org/wp-content/uploads/Image-8-2-458x600.jpg)