Getting Even: The Mighty Pen of Lady Bulwer Lytton

Cornelia King, Chief of Reference and Curator of Women’s History

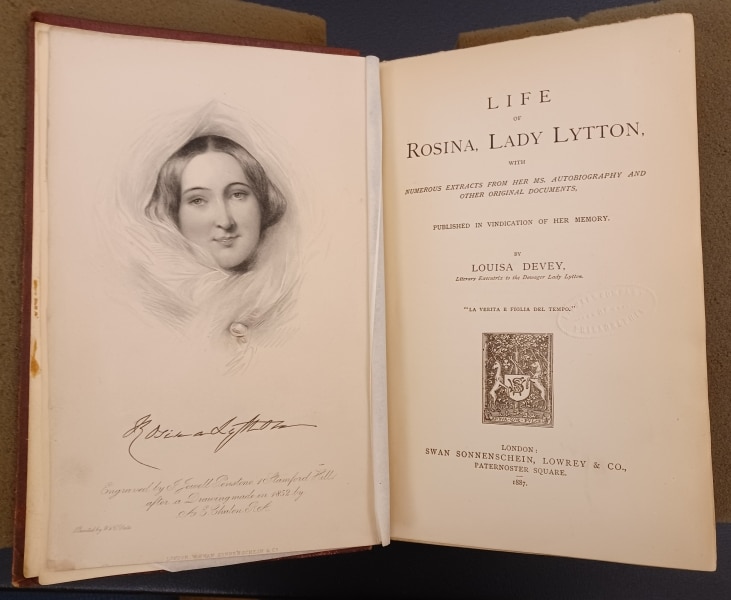

Frontispiece in Louisa Devey’s Life of Rosina, Lady Lytton (London, 1887).

Prolific writer Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803-1873) is best-known today for the opening words of his 1830 novel Paul Clifford: “It was a dark and stormy night” and the oft-quoted statement “The pen is mightier than the sword” (from his 1839 play Richelieu). Less well-known today is the fact that he had a very stormy marriage, and his estranged wife Rosina Bulwer Lytton (1802-1882) fictionalized his infidelities in her novel Cheveley, or, The Man of Honour (1839).

In 1858, when Edward Bulwer-Lytton was running for office, Rosina denounced him publicly. As a consequence, he had her committed to an asylum. He allowed her to be released shortly thereafter, in the wake of negative publicity. In 1866, Rosina wrote an account of the experience, which appeared over a decade later, in 1880 (seven years after Edward’s death), with the title A Blighted Life.

However, it is Rosina’s remarkable novels, published between 1839 and the early 1870s, that best give her perspective on what happened after the Bulwer-Lyttons’ relationship turned sour. Following Rosina’s death in 1882, her executrix continued the effort to vindicate Rosina in the court of public opinion by issuing two books, both containing transcriptions from her manuscript autobiography. The public had a lot of opportunities to know details about the couple’s decades-long grudge match.

Finances plagued Edward and Rosina’s relationship from the start. In 1827, they married against the wishes of Edward’s mother, who consequently reduced his allowance. In the early years, the couple relied on Edward’s novel-writing for their support. By 1834, the tensions in their relationship were exacerbated when Edward brought his mistress with them to Italy. In 1836, they were legally separated.

After the death of his mother in 1844, Edward became a wealthy man. Meanwhile, Rosina (now known as Lady Bulwer Lytton as a result of the death of her mother-in-law) lived in poverty. Edward limited Rosina’s access to money in an effort to force her to grant him a divorce. Her creditors believed her to be a wealthy woman. She, too, wanted a divorce, but not on the terms Edward was offering. In the following decades, she wrote over fifteen novels, mainly on themes related to her own circumstances. As literary historian Marie M. Roberts has noted, in Rosina’s novels, she “explores the tyranny of romantic love and the way it lures women into the unequal partnership of marriage.”

Additionally, Edward pressured his publishers not to publish Rosina’s books. So, as a consequence, her books appeared with the imprints of minor British publishers who were themselves financially insecure. In 1994, Roberts identified seventeen titles by Rosina, some of which were issued anonymously or under pseudonyms. Since that time, more titles have been identified. As literary historian Virginia Blain has noted, today Rosina’s books are largely unobtainable, although her writing is “lively and observant, subversively witty, and certainly original.”

The Library Company has a few books by Rosina Bulwer Lytton, some in London editions, and others in American or French editions.

Rosina’s 1839 novel Cheveley, or, The Man of Honour appeared after the couple had separated but before Edward received his inheritance. In it she skewers her husband, thinly disguised as the fictional character Lord De Clifford, who seduces and betrays the daughter of one of his tenants. The young woman goes mad, but eventually denounces him in court. Revealed as the tyrant he is, he rushes from the courtroom, leaps onto his horse, and almost immediately falls from the horse to his death, perhaps as a result of a gypsy curse. Rosina dedicated the book to “No One Nobody, Esq … the only man whose integrity I have found unimpeachable and whose friendship I have proved unvarying.” Issuing it was clearly an act of revenge against Edward, and men generally.

In 1839, London publisher Edward Bull brought out Cheveley as a three-volume set, issuing a second edition the same year. We don’t know the arrangements Rosina made with Bull, but one 20th-century literary historian describes him as a “vanity publisher,” so Rosina may not have earned much if any money. That same year, a Paris firm issued a one-volume edition in English, and a Stockholm firm issued a three-volume edition in Swedish. Before the existence of international copyright protection, the foreign reprints would not have produced any income for Rosina at all.

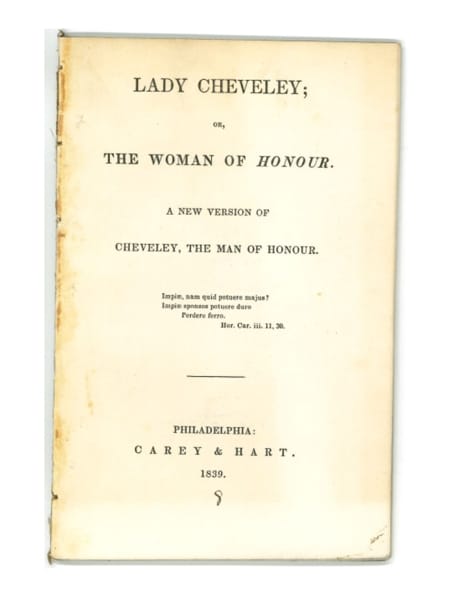

The Library Company has a copy of the first American edition of Cheveley, issued by the New York firm of Harper & Brothers in two volumes in 1839, which came to us in 1869 as part of the Rush bequest. But the item I want to show you is this satiric response to the book: Lady Cheveley, or, The Woman of Honour, which first appeared in a London edition in 1839.

The Library Company has a copy of the Philadelphia edition issued by Carey & Hart, also in 1839, which came as an 1881 gift to us from Library Company shareholder Charles Ingersoll. Issued anonymously, this 47-page pamphlet is a satiric poem in response to Rosina’s novel Cheveley, or, The Man of Honour. Literary historian Marie Mulvey-Roberts suggests that the author was most likely Edward Bulwer-Lytton himself. Consider the hypocrisy if that is true! In the poem, Edward would be characterizing himself as the upright Victorian husband wronged, while Rosina is “safe in ambush, [aiming] the dart of coward malice at a husband’s heart.”

The most hypocritical lines would be:

But his were trials which no muse may sing.

To spare the viper, while he felt the sting!

To know the sanctity of home defiled!

To blush for her, the mother of his child!

In silent pride his cruel wrongs to bear ….

If this is Edward’s poetic rebuttal, it is indeed totally hypocritical of him to say he’s silently enduring wrongs. This is the general criticism underlying all of Rosina’s specific criticisms: that Edward presented himself as the model of Victorian propriety, while actually being anything but. She came to call him “Sir Liar.”

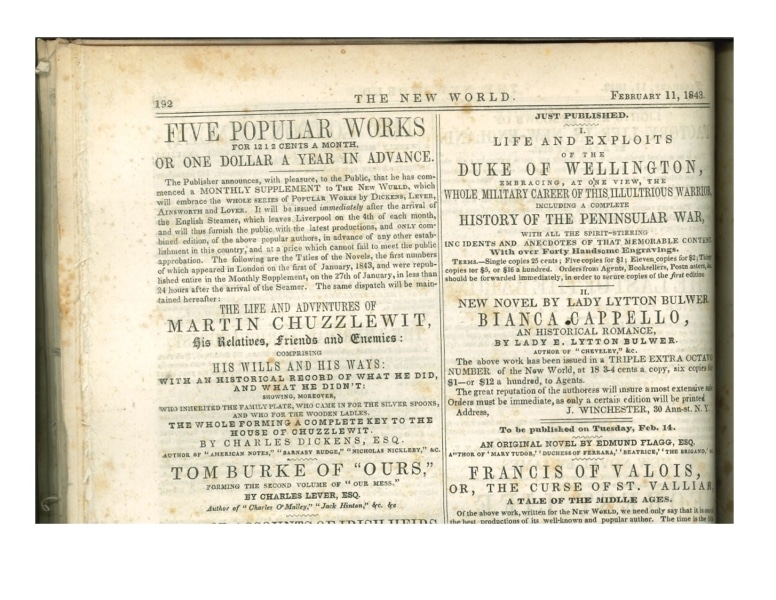

As I mentioned, the foreign reprints would not have produced any income for Rosina. For example, New York publisher Jonas Winchester issued her Bianca Cappello and her Man of the People (written under the pseudonym “C.G. Rosenberg”) in 1843, initially in the “Extra Series” for his weekly paper the New World, and subsequently as monographs in his “Books for the People” series. Winchester made no secret of his practices. He sent books that arrived from England and the Continent directly to compositors, with presses often running through the night, in order to bring books out ahead of rival publishers. Note the ad for Dickens’ Martin Chuzzlewit: Winchester claims that the book appeared in London on January 1, 1843, left Liverpool on a steamer on January 4th, arrived in New York on January 27th, and was available for sale as a monthly supplement to the New World in less that twenty-four hours! Winchester was one of a number of New York publishers who vied to issue Dickens’ works as soon as possible after the London editions, so that would have been a major overnight project for compositors working for him. Perhaps Winchester’s edition of Rosina Bulwer Lytton’s Bianca Cappello wasn’t quite as rushed in production, but Winchester knows his selling point for her book; the ad copy states, “The great reputation of the authoress will insure a most extensive sale.” By “great reputation,” he surely means her notoriety for impugning her husband’s character in print.

Rosina’s 1843 novel about the 16th-century Italian noblewoman Bianca Cappello presents Bianca initially as an appealing young woman celebrated for her beauty and wit (much as Rosina was before her marriage to Edward). It is her husband’s betrayal that transforms Bianca into “a bold, brave woman, ready to play the game of life,” which is also how Rosina perceived herself. The historical Bianca Cappello became the mistress of Francesco de Medici, and may have conspired with him to murder her husband after he had been unfaithful to her. Rosina’s choice of subjects might well have been a subtle (or not-so-subtle) way of suggesting that Edward should watch his back, after his infidelities in their own marriage.

The enterprising Jonas Winchester (and his New World Press) and other New York publishers were not the only American publishers to take advantage of the opportunity to reprint a novel by Rosina, presumably paying her no royalties. In 1852, Abraham Hart issued The School for Husbands the same year it appeared in London as The School for Husbands, or, Molière’s Life and Times.

Hart had been Edward Carey’s partner until his death in 1845. The connection with Edward Carey, who was prominent Philadelphia publisher Mathew Carey’s son, was a distinction that Hart sought to continue capitalizing on by putting the phrase “late Carey & Hart” in his imprints. Previously, Carey & Hart was the firm that had re-published the satiric response to Cheveley – the poem that Edward Bulwer-Lytton may have written in revenge. It seems that the firm was not averse to playing both sides of this grudge match. In The School for Husbands, Rosina rails against the institution of marriage with proto-feminist statements like, “Marriage annihilates a woman’s power and renders her a nullity … and cannot have a moral tendency, for it is unjust.” But people read Rosina’s books because of the scandalous circumstances of the Bulwer-Lyttons’ marriage and not for her radical politics. As literary historian Virginia Blain has noted, “Although she was often listened to with fascination, she wasn’t really heard.”

Blain also notes how Rosina suffered from the “cultural insistence on seeing female anger as a form of insanity.” In 1858, when Edward was running for office, Rosina spoke publicly against his character. As mentioned previously, Edward retaliated by having her committed to an asylum. Her friends supported her and generated so much publicity that she was released after only a few weeks.

Not surprisingly, Rosina decided to write about the experience of her husband placing her in an asylum. Apparently, she finished the manuscript for her A Blighted Life by the late 1860s, but it wasn’t published until 1880, seven years after Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s death. As Marie Mulvey-Roberts points out, this time Rosina speaks about her own experiences, naming her husband as the target of her anger explicitly. Although the message was very little different from that in her novels, the fact that she openly vilified the late Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton (as well as Queen Victoria for having made him a peer) did not help her garner support from the public, and also alienated her son Edward Robert Bulwer Lytton (1831-1891).

Following Rosina’s death, two years later in 1882, her cause was taken up by her executrix, Louisa Devey, who published a biography of Rosina that contained extracts from the autobiography she left in manuscript. Note that is was published “in vindication of her memory.”

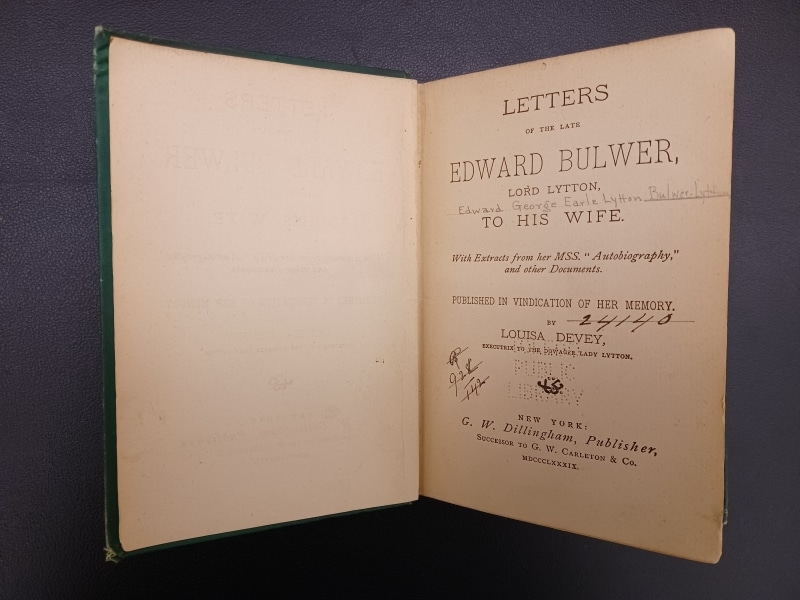

Devey also published another volume in vindication of Rosina’s memory, which contained 301 love letters written by Edward to Rosina when they were a young couple in love:

In some of them, Edward calls Rosina “Poodle” (or even “My Dearest and Darlingest Poodle”) and signs himself “Puppy.” They’re sort of cringeworthy. Here’s a brief passage: “Is oo not a darling my own gentle Poodle? Is oo not a kind love? Ah! me does, does, does love oo so, so, So, So!” The book runs to 451 pages in this American edition. Son Robert Bulwer Lytton attempted to suppress the English edition of 1884, but – not surprisingly – there are many copies listed in WorldCat. People do like to read about celebrities who behave badly!

In summary, I too am fascinated by Rosina Bulwer Lytton, who was indeed often listened to – but seldom really heard.

Suggested reading, for more about Rosina Bulwer Lytton:

Barnes, James J., Authors, Publishers and Politicians: The Quest for an Anglo-American Copyright Agreement, 1815-1854 (London, 1974).

Barnes, James J., “Jonas Winchester: Printer, Speculator, Medicine Man,” Printing History 5 (1983): 17-28.

Blain, Virginia, “Rosina Bulwer Lytton and the Rage of the Unheard,” Huntington Library Quarterly 53 (1990): 210-236.

Mulvey-Roberts, Marie, introduction to the reprint edition of Rosina Bulwer Lytton, A Blighted Life (Bristol, Eng., 1994).

Mulvey-Roberts, Marie, “‘The Very Worst Woman I ever heard of’: Rosina Bulwer Lytton and Biography As Vindication,” in Mary Hays’s “Female Biography” (London, 2019).

Wise, Sarah, “The Woman in Yellow,” in Inconvenient People: Lunacy, Liberty, and the Mad-Doctors in England (Berkeley, 2012).