John Bouvier’s Daguerreotype

Katie Maxwell, Visitor Services and Design Coordinator

John Bouvier’s Daguerreotype

While reading the Library Company exhibition Catching a Shadow: Daguerreotypes in Philadelphia, 1839-1860, I marveled at just how much detail was captured by this new invention. Daguerreotypes are produced through a direct-positive process: the image particles make up the highlights while the polished silver surface serves as the darker portions. Some of these images still appear quite clear and crisp. Daguerreotypes can, however, become damaged or corroded over time.

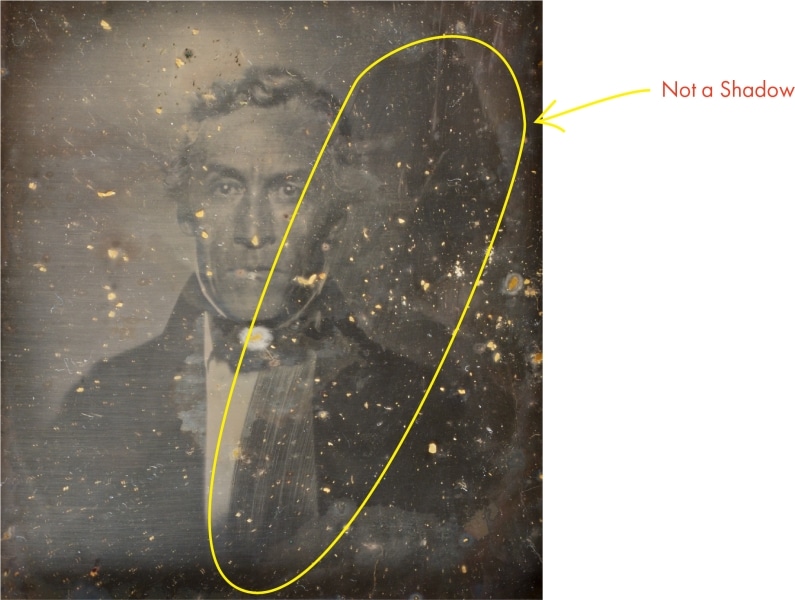

An example:

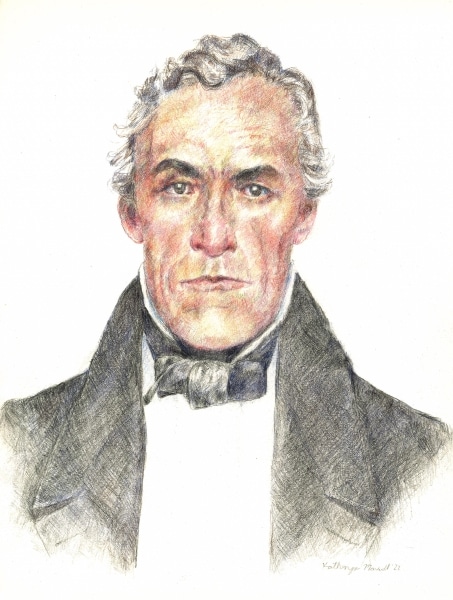

Robert Cornelius, John Bouvier (Philadelphia, ca. 1840). Daguerreotype.

John Bouvier sat for this daguerreotype while serving as a municipal judge. He immigrated from France and became known for his legal dictionary.

The first thing I noticed about this portrait was the intensity of Bouvier’s gaze. The second thing I noticed was the corrosion and damage to the plate and cover glass of the image. Gold spots mar the surface, catching the tip of Bouvier’s nose and speckling his face, while one large mark obscures his neck-wear. It struck me that damage like this can place distance between the sitter and the viewer. An observer might only offer this portrait a quick glance before moving on. Inspired by this notion, I decided to create three colored-pencil portraits based off of damaged photographs in the Library Company’s collection. Most people nowadays are used to seeing photography in color, and through these original works, I’d like to further bridge the distance between the people of the past and the viewers of the present.

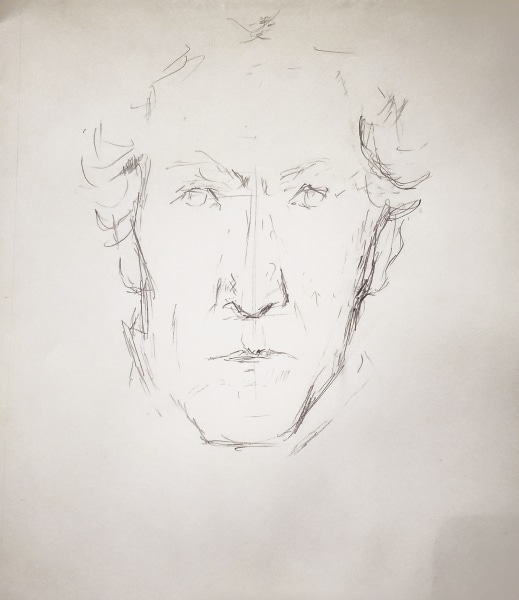

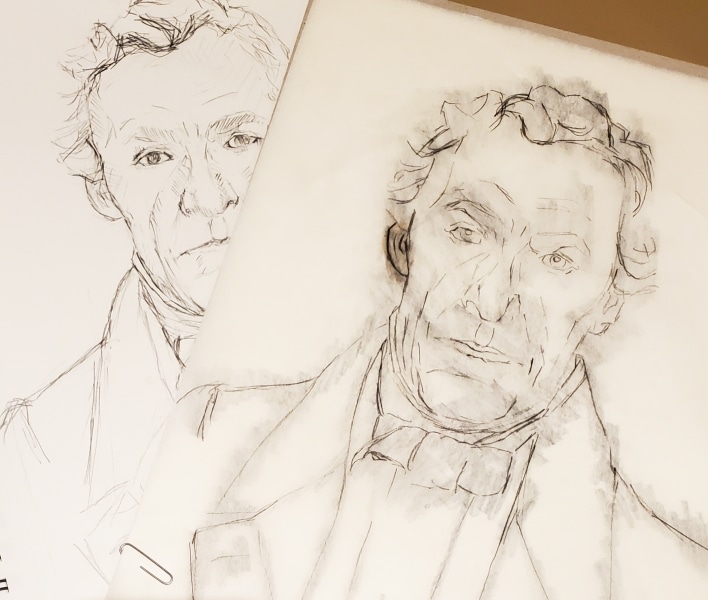

The first thing to do when attempting to capture a likeness is to study the face.

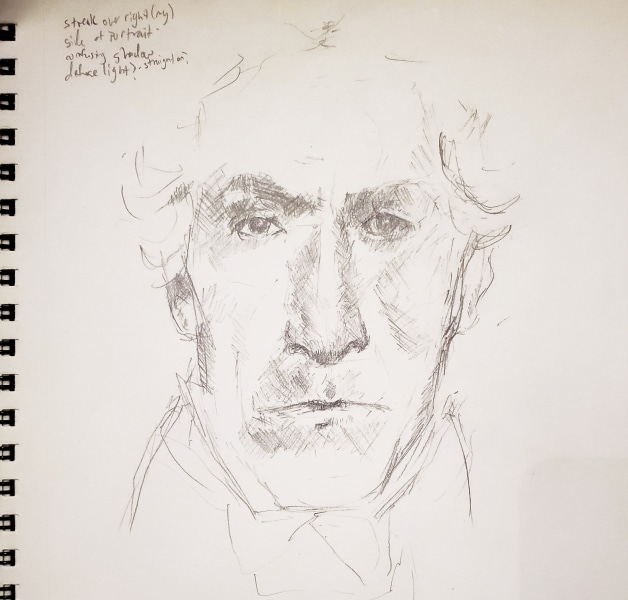

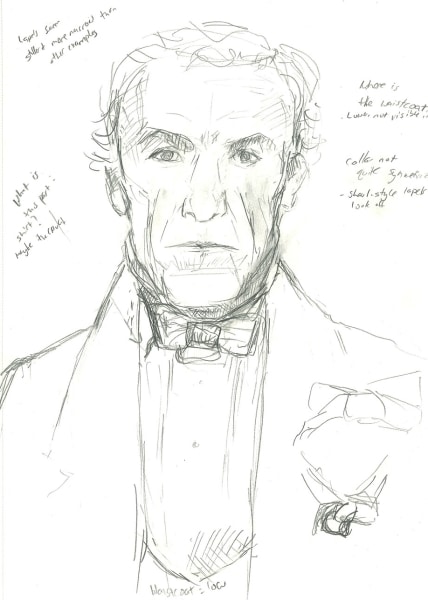

For my first sketch, I focus on Bouvier’s face. (Also, I can’t quite figure out what’s going on with the fabric around his neck, so I will save that for a different sketch.) Initially, I think there is a shadow across the sitter’s face, but it turns out that it is a streak on the surface, so I attempt to ignore it.

I’m confident that there was a diffuse light source in front of Bouvier. Excluding the streak, the shadows on his face appear roughly symmetrical. Human faces are never perfectly symmetrical; on close inspection, you’ll notice that Bouvier’s nose is crooked toward the middle as if it was broken at least once. (I wonder what happened.) I’ve also noticed that while there are highlights on his cheeks and forehead, his nose is a little darker than the rest of the face, perhaps sunburned?

The daguerreotypist took care to make sure his eyes caught the light. In an 1864 book, The Camera and the Pencil; or the Heliographic Art, It’s Theory and Practice in All Its Various Branches; e.g.–Daguerreotypy, Photography, &c …, author M.A. Root offers his thoughts and professional advice to photographers. He recommends,

“‘Catch-lights’” or white spots in [the eyes] should be thrown close to the upper lid, while made as small as possible…. They serve to impart the eyes a life-like, bright expression.”

You may notice the shape of the face is off, a bit narrow in the jaw and chin. This is what happens when drawing on a flat desk for too long before lifting the sketchbook up vertically. I’ll fix it in subsequent sketches.

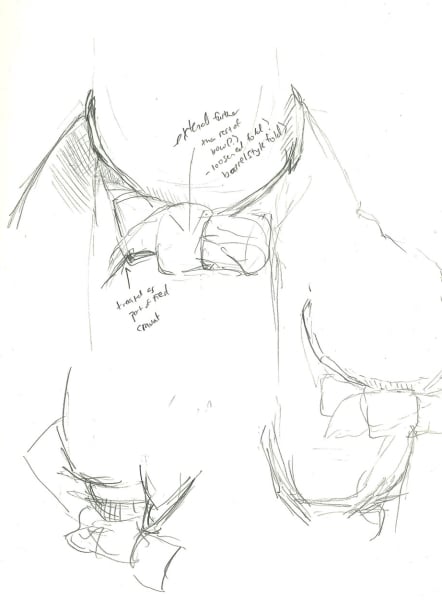

Now I need to figure out what this man is wearing around his neck.

Zooming in does not help at all. I can’t quite figure out what that pointy bit is.

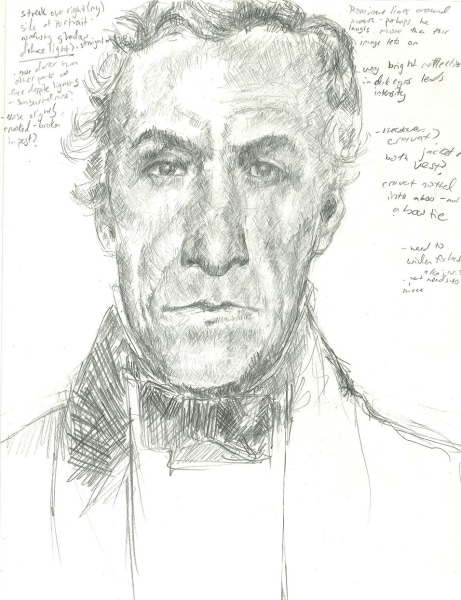

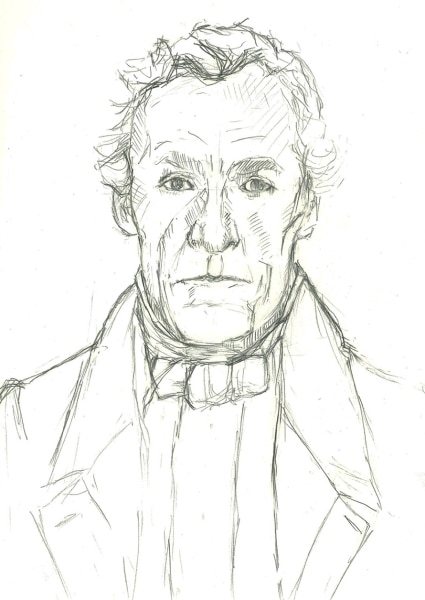

Here, I’ve sketched the face in quickly while I focus on the clothing. I still can’t quite figure out the neckwear. It isn’t a modern bow tie. It must be some sort of cravat. Looking at portraits of other mid-19th-century men should help.

Samuel Van Loan, [Portrait of an unidentified, young man with sideburns and a short beard] (Philadelphia, ca. 1848). Daguerreotype.

[Portrait of unidentified man] (Philadelphia, ca. 1848). Daguerreotype.

Both sitters wear silk (I assume) cravats tied in bows, although the bows themselves are shaped differently. The first man’s bow is very neat and rectangular while the second man’s bow displays extra material pulled from the knot. This gives me a good idea how to depict the cravat…

but the jackets are somewhat different from Bouvier’s. The lapels of his jacket sit close to his neck, while those of the younger men’s are lower on the shoulders, more similar to modern suit jackets.

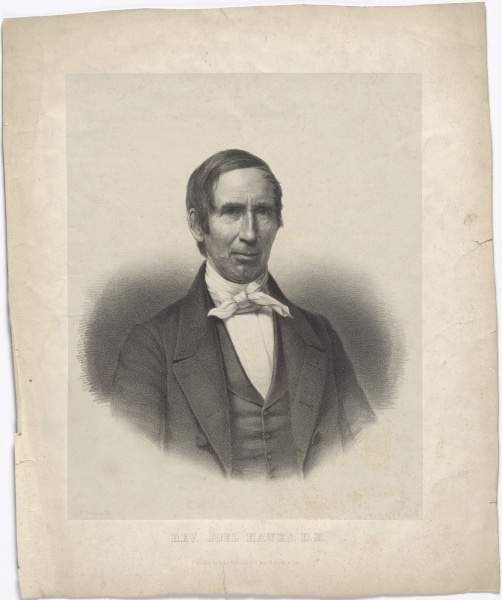

Francis D’Avignon, Joel Hawes (Hartford: Alden & Kuchel Lithography Co., ca. 1849). Lithograph. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

This lithograph shows a man wearing a strikingly similar jacket to Bouvier’s although his neckwear is a bit different.

This final sketch incorporates the jacket of the National Portrait Gallery image and elements of the cravats worn by the unidentified young men in the daguerreotypes.

Rather than re-drawing Bouvier’s portrait into the final drawing, I am transferring it with graphite and tracing paper.

To transfer a sketch to the final drawing paper:

- Lay tracing paper over the sketch and trace over it with pen or pencil

- Turn the tracing paper drawing over, and scribble with a graphite stick, ensuring all lines are covered

- Lay the tracing paper graphite-scribbled-side down on the final paper, and trace over the drawing one last time with pen or pencil.

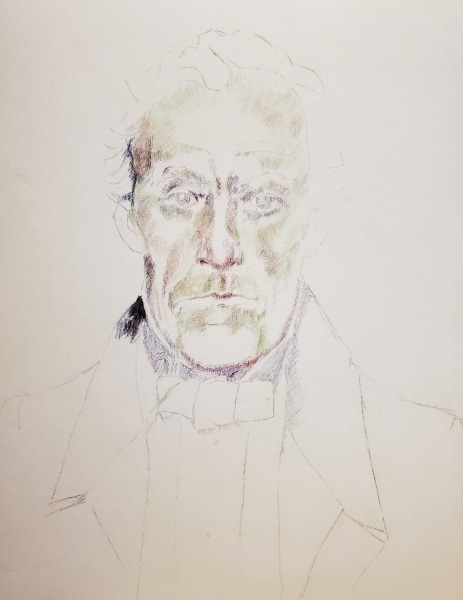

As I make the transition to colored pencil, I start shading the undertone of the face in shades of green and block in a little bit of dark color on Bouvier’s collar for comparison.

Next, I add in shades of orange and purple. I never use a single color (such as “peach”) on a face because skin is layered and translucent.

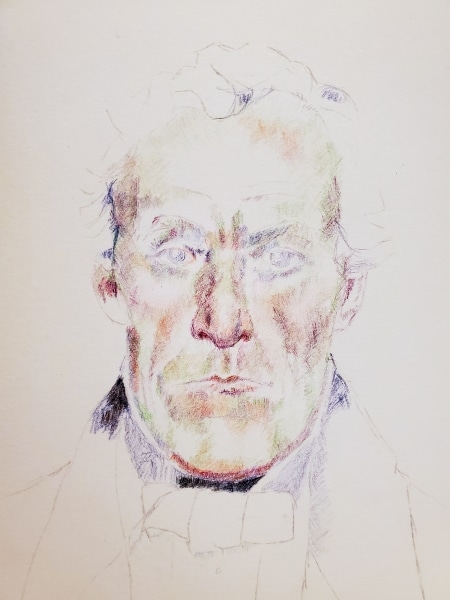

In the original image, the shadows on Bouvier’s jaw are as dark as his coat. The whole image is so dark, it makes it difficult to see where his jaw ends and his clothes begin. I’m lightening the shadows up a bit and pushing the highlights on the chin, nose, forehead, and the tops of the cheekbones. I have to guess the exact structure of his jaw.

Here, the face and hair are nearly finished with just a few details still to go. In order to render Bouvier’s hair, I used dark brown, dark blue, and a tiny bit of black. There is a smear mark on the daguerreotype that obscures some of Bouvier’s hair, but from what I can see, his hair appears to be styled in loose waves in contrast to the image below.

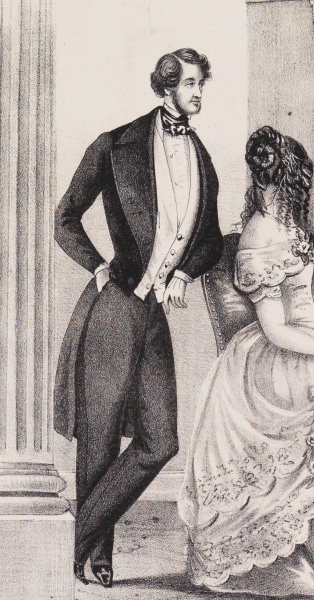

Detail: Philadelphia Fashions, Spring & Summer 1845, by S.A. & A. F. Ward no. 62 Walnut St., (Philadelphia: Sinclair’s Lith.,, ca.1845). Lithograph.

In this fashion plate, the man’s hair is slicked down near his hairline and ends in a sculptural wave curling back towards his head. Perhaps Bouvier’s photographer, Robert Cornelius, wanted to add dimension to his hair:

“The hair of a gentleman, when sitting for a heliograph, should never be carefully oiled and brushed down according to the fashion of the hair-dressers. Contrariwise it should be laid loosely up, and tossed lock above lock, so as to impart thereto a careless-seeming aspect.… [H]air … looks in a picture by far the best if sufficiently ruffled up to let the light fall into and be absorbed by it” (Root, pg 128)

I continue on to complete the jacket and cravat with the blue, brown, and black pencils. I considered making the tie blue or burgundy, but it is so dark in the daguerreotype that I play it safe and keep it black.

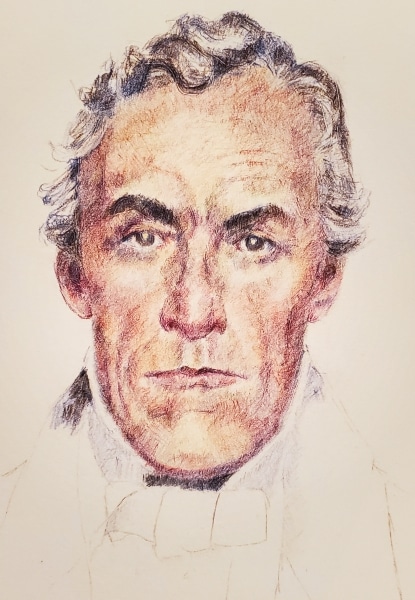

The completed portrait:

As I completed the portrait, I took care to preserve the “catch-lights” in Bouvier’s eyes. They seemed to be key to capturing his intense gaze.

Sources:

“PMG Cased Photographs: Daguerreotype.” AIC Wiki: A Collaborative Knowledge Resource. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://www.conservation-wiki.com/wiki/PMG_Cased_Photographs:_Daguerreotype.

“Daguerreotypes.” Graphics Atlas. Accessed October 5, 2022. http://www.graphicsatlas.org/identification/?process_id=366#overview

Mone, Greg. “Color Images More Memorable Than Black and White.” Scientific American. May 6, 2002. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/color-images-more-memorab/.

Root, M.A., The Camera and the Pencil; or the Heliographic Art. Philadelphia: M.A. Root J.B. Lippincott & Co.,1864. https://archive.org/details/camerapencilorh00root/page/n7/mode/2up?view=theater

Weatherwax, Sarah. “Picturing the Law: Images of John Bouvier.” The Daguerreian Society Quarterly 32 (January-March 2020), 5-7.