Independence through Self-Education: The Importance of Books and Reading in the Working Women’s Movement

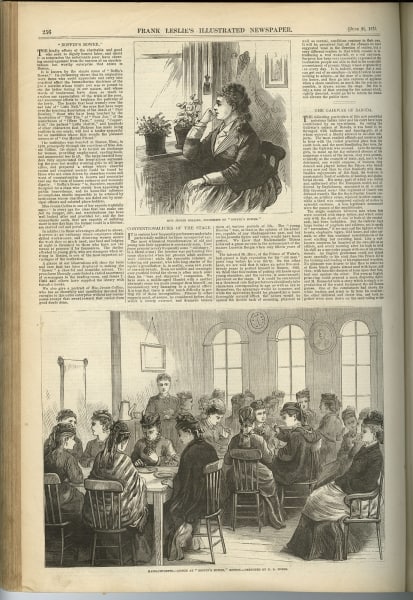

Illustration from an article on Boffin’s Bower, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper 26 June, 1875.

Last spring, we were happy but not surprised to hear that Lydia Shaw, a Franklin & Marshall College student, had been accepted into the Fulbright Summer Institute to study at Aberystwyth University in Wales. The topic of the program, “Identity and Nationhood: Contemporary Issues,” was closely aligned with her interests. Here at the Library Company, Lydia had previously completed two summer projects on 19th-century women’s issues. In 2017, she researched the writings of health and marriage reformer Mary Gove Nichols, and in 2018, she examined the life and work of Mary Abigail Dodge, a writer who became indignant on discovering that her publisher was paying her less than he was paying male writers.

This summer, Lydia returned to the Library Company to do a third project for Women’s Equality Day 2019, this time on Jennie Collins (1828-1887) and the program she started in 1870 for the benefit of working women in Boston. According to Lydia:

Jennie Collins (1828-1887) is best known for her work as a labor reformer, welfare worker, abolitionist, suffragist, and spiritualist. A native of Amoskeag, New Hampshire, Collins first went to the cotton mills of Massachusetts at the age of fourteen. She later worked as a domestic servant and a tailoress in Boston. Collins’s experiences in a variety of trades gave her the ability to approach labor reform from the collective point of view of the working women who entered the labor force after the Civil War. She herself suffered the poor conditions of factories and mills, the below-living wages paid to working women, and the limiting of women to unskilled positions.

After gaining attention for her particularly moving speech on working women’s rights in 1868, Collins became involved in the New England Labor Reform League, which was remarkable at the time for its promotion of female membership and female officers. Collins also helped found the Working Women’s League of Boston in 1869. The Working Women’s League, though short-lived, was important for its advocacy of the rights of working women. Its use of the phrase “working women,” as opposed to the commonly used phrase “working girls,” asserted a respectability and credibility of women as full citizens. Collins is well-known for her statement on the 1869 strike at the Cocheco mills in Dover, New Hampshire: “We working women will wear fig-leaf dresses before we will patronize the Cocheco Company.” Lauded for her public speaking skills, Collins would later tour the United States giving lectures to raise money for Boffin’s Bower, which she established in 1870 in Boston. The social center was funded mostly by genteel donors and factory owners. It provided food, entertainment such as music and lectures, a reading room and library, employment services, industrial training, and sometimes even lodging, to working women free of charge. A “cheerful and homelike retreat,” Boffin’s Bower was furnished with a piano and plants, and even had two canaries in its parlor. After the Boston fire in 1872, young women flocked to Boffin’s Bower for comfort, and during the winter depression of 1877-78, Boffin’s Bower served free meals to over 8,000 women.

The name “Boffin’s Bower” originated from the Charles Dickens novel Our Mutual Friend. The use of the name, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper claimed in an article, showed Collins’s ability to “carry into practical effect the humanitarian doctrines” of Dickens, known for his sympathetic portrayal of the poor. Dickens even assisted in the founding of a homeless women’s shelter in London. Unsurprisingly, Dickens was Collins’s favorite author. Collins writes in her first report on Boffin’s Bower in 1871, “The appellation selected may not sound business-like; but the name of Dickens, who originated it, is familiar in cottage and mansion, and nothing objectionable attaches to it. Besides, it suggests something rustic and unpretending—exactly what the place is at present.” Judith A. Ranta asserts in her 2010 introduction to Nature’s Aristocracy that Collins “often viewed her writing and charitable work through the lens of Dickens’s fiction.”

The actual story “Boffin’s Bower” follows Mr. Wegg, a character likely intended to be indicative of London’s poor and homeless population. One morning, Mr. Wegg is approached by a gentleman named Mr. Boffin, who is by Mr. Wegg’s account, a “very odd-looking fellow altogether.” Despite Mr. Boffin’s socio-economic class, he is illiterate. After a rather confusing exchange, in which Mr. Wegg must keep up with the overall absurdity of Mr. Boffin, he makes an offer to Mr. Wegg. Mr. Boffin states that he will pay Mr. Wegg to read a collection of books for him. By the end of the story, Mr. Boffin has been enlightened by Mr. Wegg’s knowledge and is stupefied: “I didn’t think this morning there was hald so many Scarers in Print. But I’m in for it now!”

Through the story, Dickens refutes common stereotypes of the poor, showing that they could be more educated and respectable than the rich. It was fair work for fair wages that could level the two classes and benefit both. Jennie Collins believed that unnatural socio-economic systems contradicted natural genius. Her nearly autobiographical book Nature’s Aristocracy explores the intersection of gender and socio-economic class. In it, Collins uses fictionalized narratives of the poor to reflect the collective experiences of the working-class, asserting that the working-class is outcast by the “unnatural condition of society.” She describes the “golden age of factory life,” in which intellectual activity was a part of labor: factory girls were “endowed with literary taste; and some of them wrote articles for magazines and first-class periodicals, […] Books were then seen on nearly every window-sill.” As Ranta also notes in her 2010 introduction, Collins’s book was likely modified by her editor, Russell H. Conwell. His edits likely made her book’s content and voice significantly less radical, which condescended to and invalidated her authorial voice as an intellectual and her credibility as a woman. However, the very task Collins undertook in authorship shows the importance of literature to both herself and to the working women’s movement.

The significance of literature to working women of the 1870s was also shown in many aspects of working women’s lives. During her time at the mills, Collins spent her evenings like most female mill and factory workers: gathered in a common space while someone read aloud. Many women who worked in mills and factories wrote for their own periodicals and magazines, since all they required for authorship was literacy. Therefore, self-education and literary fluency was imperative to working women because not only was reading entertainment, it also provided them with an education. Literature taught women the strong voice and intellectual credibility that they utilized in unions and political advocacy, demanding their rights. Literature served to uplift, inspire, and provide working women with the ability to advocate their rights effectively, teaching them to assert personal agency and independence.

Cornelia King, Chief of Reference & Curator of Women’s History for The Davida T. Deutsch Program in Women’s History

Lydia Shaw, Franklin & Marshall Class of 2022

Illustration from an article on Boffin’s Bower, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper 26 June, 1875.

Works Cited

“Boffin’s Bower.” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 26 June, 1875, p. 256.

Collins, Jennie. Nature’s Aristocracy; or, Battles and Wounds in Time of Peace, a Plea for the Oppressed. Boston, Lee and Shepard, 1871.

“Collins, Jennie.” Notable American Women 1607-1950. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971, v. 1, p. 362-363.

Collins, Jennie. “Plan for Future Work.” Boston, George L. Keyes, 1872.

Dickens, Charles. “Chapter V. Boffin’s Bower.” Our Mutual Friend. New York, Harper & Brothers, 1865, pp. 34-40.

Ranta, Judith A. Editor’s Introduction. Nature’s Aristocracy by Jennie Collins, University of Nebraska, 2010, pp. ix-xxxv.

Vapnek, Lara. Working Women & Economic Independence 1865-1920. Urbana and Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 2009.

![2lper-1575-f-v40-1875-p257 Illustration [or Illustrations] from an article on Boffin’s Bower, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper 26 June, 1875.](https://librarycompany.org/wp-content/uploads/2lper-1575-f-v40-1875-p257-800x562.jpg)