Li Hongzhang and Chinese Representation in America

Linda Kimiko August, Curator of Art & Artifacts & Visual Materials Cataloger

In 1896, Chinese statesmen, diplomat, and military general Li Hongzhang (1823-1901) toured Europe and the United States drawing large crowds and garnering the attention of the popular media. The most renown Chinese person of his time, Hongzhang also known as Li Hung Chang, advocated for Chinese interests in the West and played a role in encouraging China’s industrial and military modernization. His sophisticated use of his own image made him famous internationally and sharply contrasted with how the West increasingly portrayed Chinese people in racist caricature and negative stereotypes.

Hongzhang’s first diplomatic encounter with Americans began years earlier when Ulysses S. Grant visited China in 1879. After Grant’s presidency ended, he and his wife Julia embarked on a world tour of nineteen countries in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia departing from Philadelphia in May 1877 and returning to San Francisco in September 1879. While in China, Grant met with Hongzhang, the Viceroy of Zhili, and Prince Gong (1833-1898). They asked Grant to help mediate on their ongoing territorial dispute over the Ryukyu or Loo Choo islands (i.e., present day Okinawa) with Japan. Grant and Hongzhang, both war veterans, understood conflict and related to each other from their service in the American Civil War and the Taiping Rebellion, respectively. Grant initiated negotiations between the two countries but an agreement to a resolution proved unsuccessful. Chinese photographer Liang Shitai commemorated Grant and Hongzhang’s meeting in Tianjin in January 1879 with a formal portrait, which periodicals and newspapers reprinted. The portrait shows the men posed symmetrically connoting their equality as national leaders.

“General Grant and Li Hung Chang, Chinese Grand Secretary of State and Viceroy of Chi-Li,” Harper’s Weekly (October 4, 1879).

Hongzhang traveled extensively in 1896. He attended the coronation of Nicholas II of Russia, toured through Britain, meeting with Queen Victoria, visited European countries, including France and Germany, and then crossed the Atlantic Ocean to the United States and Canada. In addition to promoting Chinese diplomatic interests and trade, he was also interested in Western technology and innovations, such as railroads, factories, and ships. In America, he spoke out against the growing anti-Chinese sentiment that resulted in the passage of the first laws in the United States to specifically target an ethnic group. The Page Act in 1875 prohibited Chinese women from entering the United States. The Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 barred further immigration and declared Chinese immigrants ineligible for naturalization. The Geary Act of 1892 required Chinese people to carry a registration certificate or face one year of hard labor or deportation. The respect and honor he received highlighted a contrast to the disparaging way Americans viewed and acted towards other Chinese people.

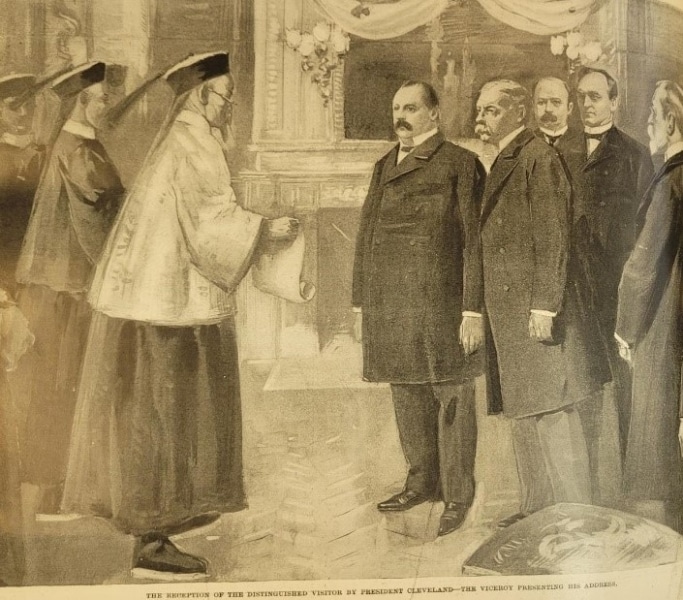

The American leg of his tour had a packed itinerary with visits to historical sites, meetings with politicians and representatives of business and industry, and numerous luncheons and dinners. He first arrived in New York on August 28, 1896. He met with President Grover Cleveland and also visited Ulysses S. Grant’s tomb with large crowds gathering to see him as he went from place to place.

“The Reception of the Distinguished Visitor By President Cleveland, The Viceroy Presenting His Address,” Leslie’s Weekly (September 10, 1896).

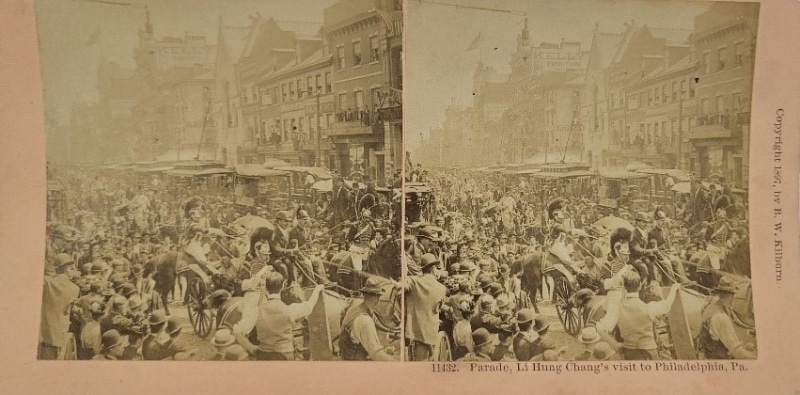

Hongzhang continued to Philadelphia, where the city strove to make a good impression and showcase their hospitality. The Citizens’ Reception Committee, comprised of a large number of notable Philadelphians, including former Mayor Edwin S. Stuart and John Wanamaker, meticulously planned every detail of his schedule. On the morning of September 3, he arrived by train to the Germantown Junction station, which was decorated with yellow bunting and red carpet. The Municipal Band played music, including the Chinese national anthem and the Star-Spangled Banner. Mayor Charles F. Warwick, General George R. Snowden, the commander of the Pennsylvania National Guard, and John Russell Young, who had previously met Hongzhang while he accompanied Grant’s visit to China, greeted him. Hongzhang, Lo Feng Lu, his interpreter and secretary, and other members of his party, then traveled by carriage in a parade procession accompanied by police on bicycles and on horseback, members of the Reception Committee in carriages, and the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry, attired in uniform and on horseback. They journeyed to Independence Hall, then to Market Street, past City Hall, and down Broad Street.

Hongzhang’s arrival caused a sensation. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that “tens of thousands gazed upon him as his carriage passed through the streets” cheering as they went by. Buildings along the route were decorated. “It was crowds, crowds, crowds, and flags, flags, flags, all the way down Chestnut Street to Independence Hall …” People lined the streets, stood on rooftops, and hung out of windows to get a glimpse of Hongzhang, attired in a yellow jacket, hat decorated with three-eyed peacock feathers, plum-colored trousers, and violet slippers. “One of the features of the great procession was the presence of all the professional and amateur photographers who could get places from which to snap a shot” resulting in stereographs like the ones shown.[1]

B.W. Kilburn, Parade, Li Hung Chang’s visit to Philadelphia, Pa. (Littleton, N.H., 1896). Detail. Li Hongzhang is visible in the carriage in the right photograph. Gift of Linda Kimiko August.

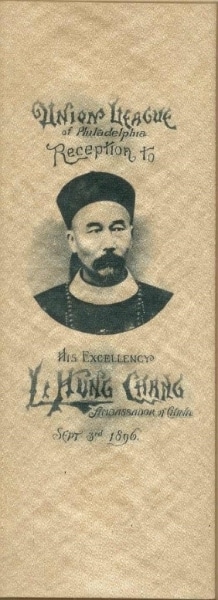

Hongzhang visited Independence Hall and saw the Liberty Bell. Mayor Warwick gave a speech declaring, “the young republic of America clasps hands with the ancient empire of Asia” to which Hongzhang responded, through his interpreter, that he wished his visit “will serve as the means of bringing the peoples into more close relations to each other, not only in politics, but commercially and literally.”[2] He next traveled to the Hotel Walton, located at Broad and Locust Streets, to eat lunch prepared by his Chinese chefs and served by his waiters, who traveled with him. Finally, the group proceeded to the Union League for a reception attended by 5,000 people. The space was decorated with flowers and Chinese dragons, and the First Regiment Band played music. Hongzhang attended the reception but was too tired to go the formal luncheon. But members of his party, including his nephew, stayed for the festivities.

Union League of Philadelphia Reception to His Excellency Li Hung Chang, Ambassador of China, Sept. 3rd 1896 (Philadelphia, 1896) and Tea and Reception to the Viceroy Li Hung Chang (Philadelphia, 1896). Courtesy of Founding Forward.

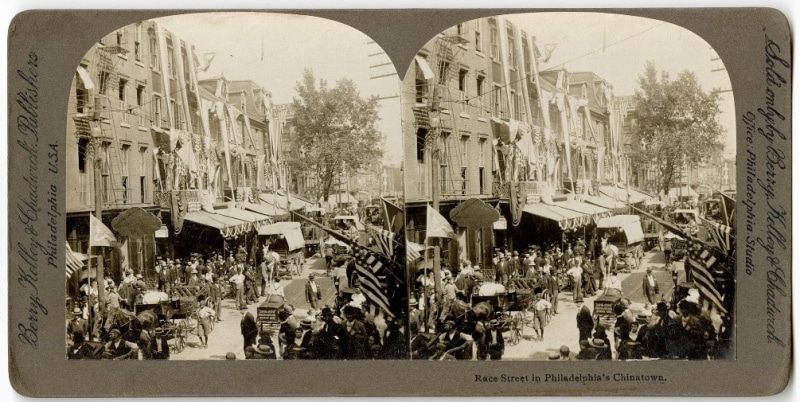

Philadelphia’s Chinatown also celebrated Hongzhang’s visit. Colorful bunting and lanterns hung on the buildings. Large crowds came through the neighborhood, “20,000 American visitors surged through Chinatown. They wandered through the various restaurants, in and out through the different tea shops and made themselves altogether at home.” The below stereograph shows Chinatown decorated with flags and large crowds walking down the sidewalks, probably taken during the visit. The Philadelphia Inquirer acknowledged the contrast between the reception Hongzhang received and the treatment of Chinese residents in Chinatown, which centered around the 900 block of Race Street. “There was something intensely amusing to the people in the contrast between the respect paid to the Viceroy and the feelings they entertained toward the residents of Race Street.”[3] A group of Chinatown residents met with Hongzhang briefly at the Hotel Walton where he inquired about their treatment and income. His interpreter Lu facilitated as the residents spoke Cantonese, not Mandarin. Certainly, the Chinese in Philadelphia hoped Hongzhang’s visit would help in creating better equality and improving their situation. Did Philadelphians become more open-minded because of the experience or had it been a voyeuristic spectacle?

Berry, Kelley & Chadwick, Race Street in Philadelphia’s Chinatown (Philadelphia, ca. 1896). Raymond Holstein Stereograph Collection.

As part of his diplomatic visit, Hongzhang raised the issue of inequality through the American press. In a meeting with newspaper reporters in New York, he condemned the Chinese Exclusion Act and argued that it should be repealed. He described how he constantly received petitions from his fellow countrymen that had come to the United States, particularly in California, “declaring that they were not treated well. Privileges received by other foreigners coming to this country had not been afforded them. They were treated badly.”[4] “My assistance was continually invoked to secure their rights. Instead of being able to do so your congress curtailed what rights they had and made their situation worse.” [5] He also pointed out the unfairness of the law in terms of competition in business. “You pride yourselves upon your liberty and freedom, but there is no freedom of labor where certain people are discriminated against and excluded.” [6] In protest, Hongzhang refused to journey through the western states and instead traveled through Canada to the Pacific Coast after visiting Washington, D.C. and Niagara Falls. “ I could not pass though States where these [Chinese] have been and are suffering.” Though “… public respect for him [Hongzhang] was general and deep-seated” the same did not extend to other Chinese people living in America. [7] On October 3, he sailed from Vancouver and returned to China.

Hongzhang understood the importance of representation and actively cultivated his public image. He recognized the significant role of photography and sat for both Chinese and Western photographers. He chose his appearance and dress, pose, and demeanor to portray a learned, sophisticated, stately, and elite man, often looking directly at the viewer. These photographic portraits follow the tradition of formal Chinese painted portraits. His likeness was extensively reproduced domestically and internationally, and he became the most prominent and recognizable Chinese person of the time. [8]

Lorenzo Fisler, “His Excellency Li Hung-Chang, Grand Secretary of the State, Viceroy of Chihli, &c., &c.,” The Far East 1, no. 3 (September 1876).

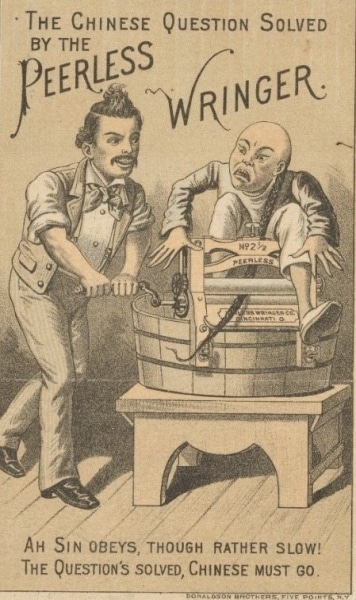

Hongzhang was not totally immune to being caricatured. His popularity resulted in his likeness being used in advertisements, postcards, and even pins. He represented the Chinese people, who increasingly the media depicted in racist stereotypes with exaggerated features. This trade card advertising the Peerless Wringer is one of many that illustrates the anti-Asian hate published extensively at this time and visible in the era’s popular and visual culture. Even when portrayed in caricatures, Hongzhang remains recognizable as an individual, such as in this print in Vanity Fair, where he is attired in his signature scholar’s cap and yellow jacket.

The Chinese Question Solved by the Peerless Wringer (New York, ca. 1875). Robert Staples Metamorphic Collection.

American Pepsin Gum. Co. Li Hung Chang, Chinese Statesman (Newark, N.J.: Whitehead & Hoag Co., 1896). Courtesy of the author

Jean Baptiste Guth, “Li” Vanity Fair, August 13, 1896. Gift of Linda Kimiko August.

Hongzhang’s visit occurred at a difficult and complicated time in terms of foreign and race relations in America. It showed the two nations moving increasing towards globalization and the social, political, and economic conflicts that arised from it. The reaction to Hongzhang illustrated America’s fascination with China. Closer study also reveals deeper insight to how Philadelphians viewed and treated the Chinese residents of the city. Though Hongzhang spoke against the plight of the Chinese in America and protested the Exclusion laws, they would not be repealed until 1943. He proved a powerful symbol of dignity and respect that countered negative Western stereotypes.

[1] “Li Hung Chang Came, Saw and Was Mightily Pleased.” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 4, 1896.

[2] “Li Hung Chang Came, Saw and Was Mightily Pleased.” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 4, 1896.

[3] “Li Hung Chang Came, Saw and Was Mightily Pleased.” Philadelphia Inquirer. September 4, 1896.

[4] “Talk with Li Hung Chang.” New York Tribune, September 3, 1896.

[5] “Exclusion of Chinese: What Li Hung Chang Says of the Law,” Kalamazoo Gazette, September 4, 1896.

[6] “Talk with Li Hung Chang.” New York Tribune, September 3, 1896 and “Plan Talk by Viceroy Li., The Evening Post (NY), September 2, 1896.

[7] Franklin Matthews, “Li Hung Chang’s Visit,” Harper’s Weekly, September 12, 1896.

[8] For more about Li Hongzhang and photography see Roberta Wue.,“The Mandarin at Home and Abroad: Picturing Li Hongzhang,” Ars Orientalis 43 (2013): 140-156.