Treasures at the Library Company of Philadelphia

In 1731, Philadelphia was North America’s most important city. It was also the canvas for many of the young Benjamin Franklin’s inspirations for voluntary association and civic betterment.

In 1731, Philadelphia was North America’s most important city. It was also the canvas for many of the young Benjamin Franklin’s inspirations for voluntary association and civic betterment.

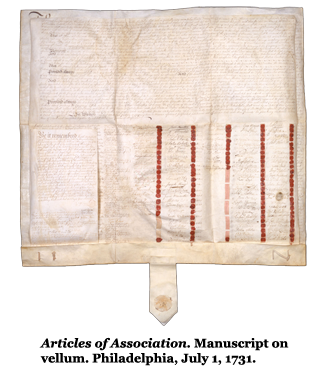

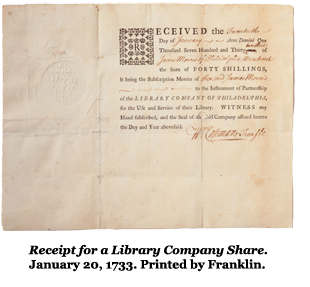

Soon after arriving in Philadelphia, Franklin had organized the Junto, a group of like-minded aspiring artisans and tradesmen who hoped to improve themselves while they improved their community. Requiring access to books to feed their discussions of the issues of the day, the Junto members initially shared their own. Given the rarity and expense of books at the time, however, even their collective possessions fell short of satisfying the young men’s needs. It was then that Franklin conceived the idea of a subscription library, into which members would pay to buy books that could be shared by all. Created as a “company,” with 50 shareholders subscribing 40 shillings each and committing to paying 10 shillings a year each, the Library Company of Philadelphia was born.

Today the idea of a lending library is such a commonplace—and such an essential feature of civilized society—that it’s worth noting how revolutionary the inspiration was in the early 18th century. The only significant libraries of the time were in the possession of a handful of private colleges or individual learned gentlemen. Franklin’s successful experiment was quickly copied up and down the Atlantic seaboard from Salem to Charleston.

Today the idea of a lending library is such a commonplace—and such an essential feature of civilized society—that it’s worth noting how revolutionary the inspiration was in the early 18th century. The only significant libraries of the time were in the possession of a handful of private colleges or individual learned gentlemen. Franklin’s successful experiment was quickly copied up and down the Atlantic seaboard from Salem to Charleston.

Describing his “first Project of a public Nature” years later in his autobiography, Franklin wrote that the Library Company “was the Mother of all North American Subscription Libraries now so numerous.” And that “These Libraries have improv’d the general Conversation of the Americans, made the common Tradesmen and Farmers as intelligent as most Gentlemen from other Countries, and perhaps have contributed in some degree to the Stand so generally made throughout the Colonies in Defense of their Privileges.”

The first book orders were sent to the Library’s agent in London, the Quaker merchant and naturalist Peter Collinson, and the collection began to grow through gift and purchase. The printed catalog of 1741—the oldest to survive—shows the breadth of early members’ interests: history & geography, literature, science, theology, philosophy & natural history, economics, art, linguistics, and social sciences. As the city’s primary cultural institution, the Library became the destination for a range of valuables and curiosities in addition to books. Donors offered antique coins, fossils, fauna preserved in spirits, unusual geological specimens, tanned skins, even the hand of a mummified Egyptian princess sent over by the painter Benjamin West.

The first book orders were sent to the Library’s agent in London, the Quaker merchant and naturalist Peter Collinson, and the collection began to grow through gift and purchase. The printed catalog of 1741—the oldest to survive—shows the breadth of early members’ interests: history & geography, literature, science, theology, philosophy & natural history, economics, art, linguistics, and social sciences. As the city’s primary cultural institution, the Library became the destination for a range of valuables and curiosities in addition to books. Donors offered antique coins, fossils, fauna preserved in spirits, unusual geological specimens, tanned skins, even the hand of a mummified Egyptian princess sent over by the painter Benjamin West.

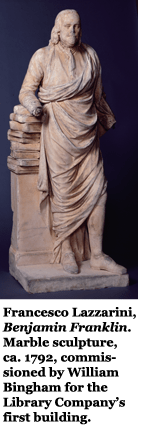

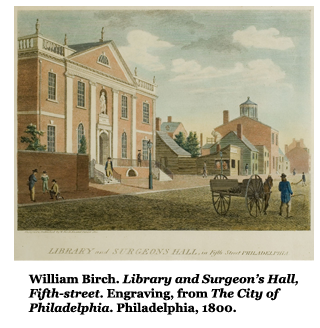

Originally, the books were kept in the homes of the first librarians, but in 1740 the collection was moved to the second floor of the State House of Pennsylvania, now Independence Hall, where it stayed until 1773. Moving into a building at 5th and Chestnut built expressly for it in 1790, the library served as the de facto Library of Congress through 1800, when the capitol moved to Washington. Library Company trustees had voted to offer free use of the collections to the delegates to the First and Second Continental Congresses, as well as the Constitutional Convention of 1787 and the federal congresses of 1790 through 1800. The Library Company was the largest public library in North America until the Civil War and the rise of free public libraries in  the second half of the nineteenth century.

the second half of the nineteenth century.

The Library Company is now a great scholarly and research library with 500,000 rare books, pamphlets, and broadsides; more than 160,000 manuscripts; and almost 100,000 graphic items, and offering fellowships to 45 scholars a year. Free and open to the public, the Library Company also presents conferences, symposia, and exhibitions on site and offers access to a large number of exhibitions and extensive source material on line.

We are pleased to share our story and some of the treasures of our collections with the New Yorker’s readership this fall. Come back to this page each week to learn more about the subject of the latest ad to appear in the magazine. Better yet, stop by when you’re in the City of Brotherly Love and Sisterly Affection. We still have the first books that Franklin and his Junto bought for their library almost 282 years ago—and we even still have that mummy’s hand.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!