Treasures from the Library Company of Philadelphia

![Aristotle, pseud. Aristotle's Complete master-piece. (London [i.e., Boston], 1766.)](http://www.librarycompany.org/treasures/essays/Ad7_ny-am1766ari-108824-o-f_sm.png) Women, want to know if you are fertile? Here’s what Aristotle prescribes. “Make a fumigation of red storax, myrhh, cassiawood, nutmeg, cinnamon, and letting her receive the fume into her womb, covering her very close. If the odor passeth through the body up into the mouth and nostrils, she is fruitful.”

Women, want to know if you are fertile? Here’s what Aristotle prescribes. “Make a fumigation of red storax, myrhh, cassiawood, nutmeg, cinnamon, and letting her receive the fume into her womb, covering her very close. If the odor passeth through the body up into the mouth and nostrils, she is fruitful.”

Aristotle’s Masterpiece was the most popular book about women’s bodies, sex, pregnancy, and childbirth in Britain and America from its first appearance in 1684 up to at least the 1870s. More than 250 editions are known, but all are very rare, so the Library Company’s 55 editions amount to perhaps the largest collection in America. This is just a tiny part of our popular medicine collection, which is made up of nearly 5,000 books and pamphlets and 8,000 pieces of ephemera printed in America before 1920 offering what we now call consumer health information. The collection is particularly strong in books about alternative approaches such as phrenology, homoeopathy, Thomsonian (botanic) medicine, and hydropathy (water cure methods). The core of the collection, however, deals with medical care in the home, including diet, exercise, patent medicines, nursing, midwifery, child care, birth control, and sex–which brings us back to Aristotle.

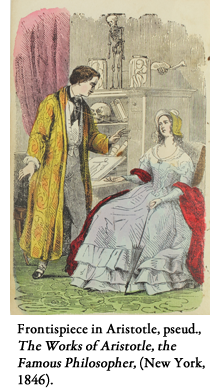

Aristotle’s Masterpiece was not written by Aristotle the ancient Greek philosopher; it was assembled from a number of popular medical works by an unknown hack writer. It is a bizarre assortment of superstition, folklore, and sex facts and fancies, all mixed in with the sort of common-sense medical advice that had been passed down by midwives for centuries.  The text changed very little over the years, but it was often rearranged, as historian Mary Fissell has noted, like a reshuffled deck of cards. Most editions had the same crude woodcut illustrations of a child in the womb and of a few monstrous births, such as the woman covered in hair from head to toe, which was said to be the result of her mother looking on a picture of John the Baptist clothed in animal skins while she was pregnant. The frontispiece usually showed the philosopher in his study contemplating a more or less unclothed woman. This was one of very few erotic images available to the common reader, and this, combined with an unusually frank discussion of human reproduction, made Aristotle’s Masterpiece a dirty book, indeed the dirty book of the early modern period. It was sold furtively by country peddlers and in general stores and taverns; regular booksellers seldom advertised it, though they usually had it under the counter.

The text changed very little over the years, but it was often rearranged, as historian Mary Fissell has noted, like a reshuffled deck of cards. Most editions had the same crude woodcut illustrations of a child in the womb and of a few monstrous births, such as the woman covered in hair from head to toe, which was said to be the result of her mother looking on a picture of John the Baptist clothed in animal skins while she was pregnant. The frontispiece usually showed the philosopher in his study contemplating a more or less unclothed woman. This was one of very few erotic images available to the common reader, and this, combined with an unusually frank discussion of human reproduction, made Aristotle’s Masterpiece a dirty book, indeed the dirty book of the early modern period. It was sold furtively by country peddlers and in general stores and taverns; regular booksellers seldom advertised it, though they usually had it under the counter.

The book played a dramatic role in a 1744 scandal in the Northampton, Massachusetts parish of Jonathan Edwards, a leading figure in the religious revivals now known as the First Great Awakening. A group of young men had somehow obtained a copy, and they were using their newfound knowledge of female anatomy to taunt and harass the young women in the parish, saying things like, “When will the moon change girls? I believe you can tell. I believe you have circles round your eyes.” Edwards formed a committee to discipline the boys. The parishioners were initially supportive, but when he named from the pulpit all the boys he suspected of being involved, mixing offenders with mere witnesses and including boys from some leading families, much of the parish turned against him. Apparently the parents were not nearly as shocked and concerned as he was. When the boys were called to testify to the committee, they were rude and defiant, coming in straight from the tavern and saying things like “I don’t care a turd.” In the end only three of the boys were lightly disciplined. This was all deeply embarrassing to Edwards, because the boys were recent converts from his own revivals. The episode showed the limits to clerical authority in colonial New England, as well as the extent to which the book was tolerated.

![Frontispiece in Aristotle, pseud., Aristotle’s Complete Master-piece ([New York], 1796).](http://www.librarycompany.org/treasures/essays/ad7_am1796aris-64732-d-f_sm.png) Toward the end of its long heyday, Aristotle’s Masterpiece began to modernize. Illustrated here are the frontispieces of two editions, 1796 and 1842. The first shows an image hardly changed since the earliest editions: Aristotle seated in his study surrounded by his books, lost in contemplation of the mysteries of generation. Standing next to him is a naked woman, whom he totally ignores–or is he dreaming her? In the 1846 edition, the crude black-and-white woodcut has been replaced with a rather sophisticated hand-colored wood engraving, and Aristotle has been transformed into a modern physician, surrounded not just by books but also by anatomical charts and specimens in bottles, dressed not in his ancient philosopher’s robes but in a suave dressing gown. (Is his gown perhaps too casual, though, a bit suggestive of the bedroom?) The woman is now a patient seeking his gynecological advice. She is fully dressed, even stylishly so, accessorized with an umbrella, and she is now sitting, while the physician stands and gives her his undivided attention. (Is his attention perhaps a shade too intense? Is she listening too raptly?) Although the pictures are now more up-to-date, the text of the 1842 edition is much like that of the 1796 edition. Both include the fertility test quoted above.

Toward the end of its long heyday, Aristotle’s Masterpiece began to modernize. Illustrated here are the frontispieces of two editions, 1796 and 1842. The first shows an image hardly changed since the earliest editions: Aristotle seated in his study surrounded by his books, lost in contemplation of the mysteries of generation. Standing next to him is a naked woman, whom he totally ignores–or is he dreaming her? In the 1846 edition, the crude black-and-white woodcut has been replaced with a rather sophisticated hand-colored wood engraving, and Aristotle has been transformed into a modern physician, surrounded not just by books but also by anatomical charts and specimens in bottles, dressed not in his ancient philosopher’s robes but in a suave dressing gown. (Is his gown perhaps too casual, though, a bit suggestive of the bedroom?) The woman is now a patient seeking his gynecological advice. She is fully dressed, even stylishly so, accessorized with an umbrella, and she is now sitting, while the physician stands and gives her his undivided attention. (Is his attention perhaps a shade too intense? Is she listening too raptly?) Although the pictures are now more up-to-date, the text of the 1842 edition is much like that of the 1796 edition. Both include the fertility test quoted above.

Aristotle’s Masterpiece fell out of print in America in the 1870s not because it was so old-fashioned but because by then it was being published by firms that specialized in pornography, and they were put out of business by Anthony Comstock and his Society for the Suppression of Vice. It stayed in print in England, though; our last edition was published in London in 1930, and yes, it still features the same fertility test.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!