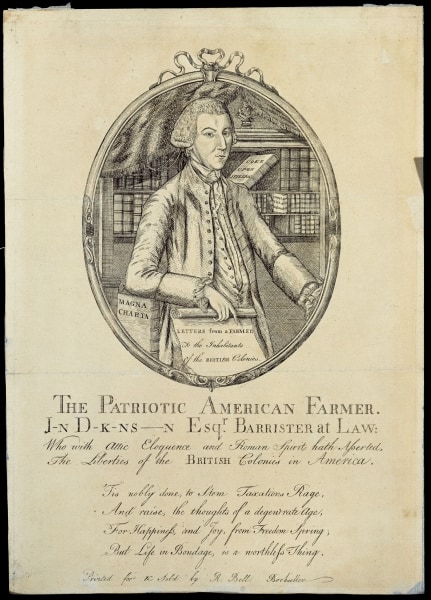

John Dickinson (1732–1808) was America’s first political celebrity. Considered around the Atlantic world as the spokesman for the American resistance to Britain, he wrote more than any other figure for the cause and then, later, the establishment of the nation’s political institutions. He was the only major figure present and active at every domestic phase of the Founding, from the Stamp Act of 1765 to through the Federal Convention of 1787. Although many considered him the leader of the Revolution, he actually did not want independence. His main concern was American rights and liberties, which, as a thoughtful lawyer, he knew were not yet sufficiently protected by American institutions at the time of the Declaration of Independence, which he refused to sign. History in both the short and long term suggests his concerns were warranted. But when his colleagues in Congress decided on independence, he took up arms, joining the Pennsylvania battalion he raised. Then later, he did what no other leading figure did—he enlisted in the Delaware militia as a private. He continued his leadership as the president of Delaware, then Pennsylvania, president of the Annapolis Convention, and active member of the Constitutional Convention. He also became an abolitionist, the only leading Founder to free all of his significant number of slaves, and an advocate for the rights of women, prisoners, Indians, and other vulnerable populations.