Curator’s Favorite: Pictures of (Un) Health

Although the majority of the visual materials in the Print Department document the Philadelphia area, we do have a number of interesting graphics in our collections that complement this focus. Thanks to trustee emeritus William H. Helfand, we hold many eclectic and striking works related to popular medicine that place our extensive holdings of visual materials into an even broader context. Two that have recently caught this curator’s eye are these late 19th-century cartoons satirizing the unsanitary conditions of Central Park. The prints address wider social issues that also affected other cities, like Philadelphia.

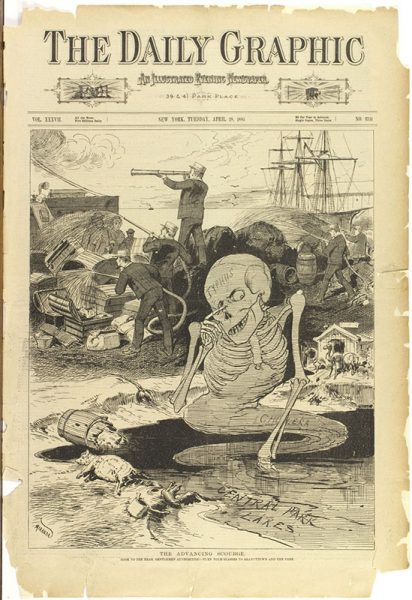

“The Advancing Scourge,” from The Daily Graphic, April 28, 1885. Photomechanical print.

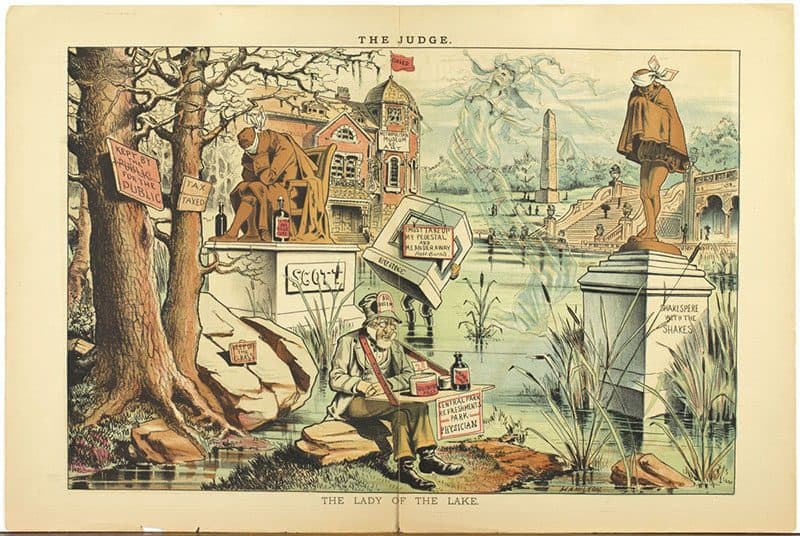

“The Lady of the Lake,” from The Judge, ca. 1883. Chromolithograph.

While today Central Park evokes images of a bucolic oasis in a bustling metropolis, not so long ago the park was viewed as not just a metaphoric, but a literal cesspool. Formed from private lands purchased by the city, like Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park, Central Park faced geographical challenges that made its development difficult as depicted in these cartoons from The Daily Graphic and The Judge.

In the mid 1880s both illustrated newspapers elicited the public’s fears of the unhealthy state of the over 800 hundred-acre park. Since its inception in the 1850s, the park had been in continual development, with ever lessening dedicated city funds. When originally laid out, the naturally swampy land required miles of drainage pipes and artificial lakes to alleviate the water problem. Poorly conceived and constructed, the pipes, by the 1880s, had become increasingly ineffective. At the time of these cartoons, fears of cholera, typhus, and malaria emanating from stagnant lakes on the public grounds swept New York City as part of the ongoing criticisms of the financial and physical mismanagement of the park.

The Daily Graphic could not resist playing a role in the public chiding when it published Fernando Miranda’s “The Advancing Scourge” on its cover on April 28, 1885. A double entendre also aimed at the fears of the ills wrought from the increasing immigration population, the cartoon uses a skeleton in “Central Park Lake” to warn that the bigger threat of disease came from within the city. The specter of death, thumbing his nose, and mired in a pool of sewage near carcasses and trash effectively makes the viewer feel as grotesque as the decayed figures portrayed look. The municipal workers hosing down those newly arrived from overseas and the burgeoning Central Park Zoo (also criticized as a den for disease) in the background furthers the disturbing message advocating for park reforms.

The circa 1883 Judge cartoon “The Lady of the Lake” by Grant Hamilton also comments on the fears of illness from the park’s drainage problem, which was especially strong among the park’s wealthy neighbors. The cartoonist centers his visual parable on Dr. Dosem, a hawker of patent medicines (and symbol of the hucksters, panhandlers, and other transients frequenting the public place), to satirize the need for a cure for the literally and figuratively ill park. To emphasize his point, nearby, Malaria(“The Lady of the Lake”) hovers over the sickened, oft-visited park statues of eminent authors William Shakespeare, Sir Walter Scott, and Robert Burns as they languish in and flee from their pernicious environs. Hamilton completes the scene (also titled after Scott’s narrative poem) and critical message through the juxtaposition of symbols of New York society’s use of the communal, yet socially segregated park. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the elite institution opened in 1880 with no hours on Sunday, overshadows the popular tourist attraction, the Egyptian obelisk, installed in 1881.

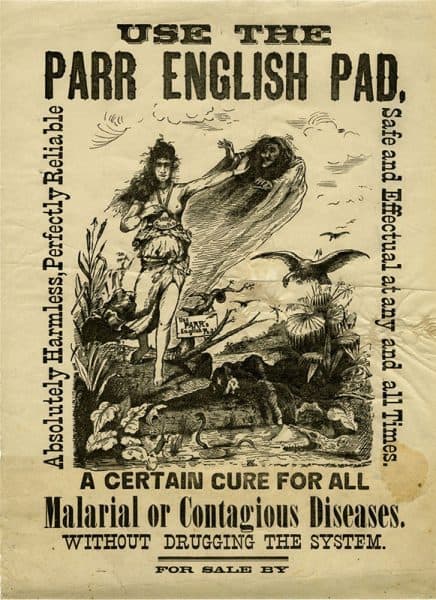

Use the English Parr Pad, A Certain Cure for All Malarial Contagious Diseases. Pittsburgh?, ca. 1885. Relief print.

Popular medicine advertisements, through similar imagery as the cartoons, also played on Victorian society’s fears of the threat of waterborne illnesses. If one should happen to fall sick from a sojourn to Central Park, the Parr English Pad manufactured by the Pittsburgh company may have served as a cure. The ominous scene includes the remedy embodied as a homely female figure, rather than the beautiful maiden used in other of the firm’s advertisements. She is as physically disconcerting as the witch-like representation of the disease she thwarts, which is likely the not-so-ironic point. Even more eerie is the female corpse who almost disappears into the foreground of this circa 1885 poster-size promotion, also from the Helfand collection.

Although not the most visually pleasing prints, these cartoons and advertisement still resonate with the viewer. The images powerfully document 19th-century fears and perceptions of swamps as dens of disease. They are timeless in their ability to make one squeamish as they provide a truly graphic history of the influential role of illness on the development of American cities (and visual culture).

Erika Piola

Associate Curator, Prints and Photographs