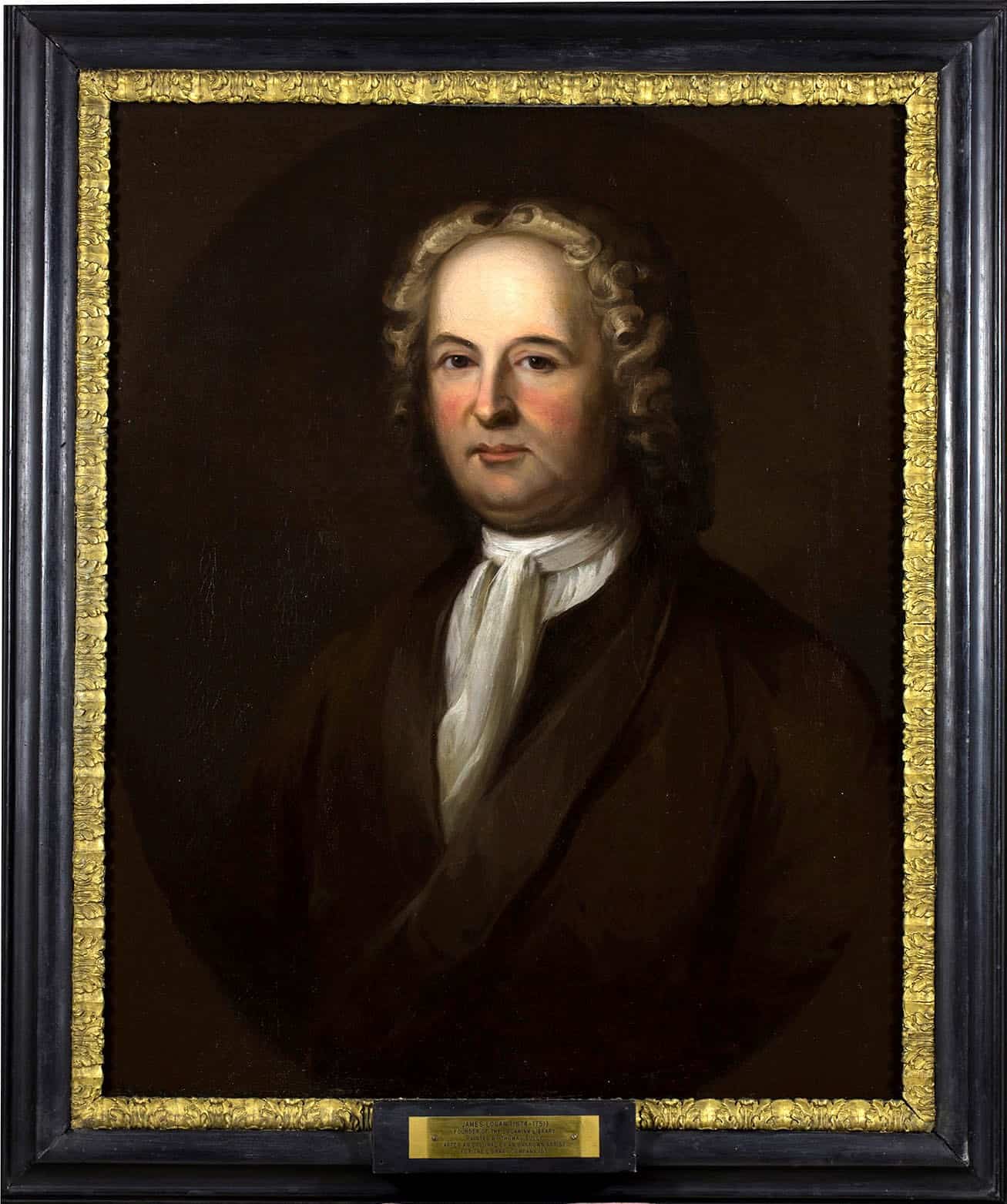

The Library Company’s Portrait of James Logan

Our portrait of James Logan by Thomas Sully is back on display after recently being restored. The story behind this painting is fascinating.

Thomas Sully (1783-1872) was one of the most prolific early American painters. A popular portraitist, he painted notable people, such as Thomas Jefferson, the Marquis de Lafayette, and Queen Victoria. The Library Company is fortunate to have eight of his works in the collection.

James Logan (1674-1751) served as William Penn’s secretary and became an influential public figure in Pennsylvania. He amassed an extraordinary collection of books of over 2,600 volumes. He left this collection for the public through the creation of the Loganian Library. In 1792, the Loganian Library was transferred to the Library Company.

The Library Company commissioned Sully to paint this portrait of Logan to replace one which had just been ruined by fire. On January 6, 1831, a fire broke out in the Loganian Library section of the Library Company. The fire destroyed some books, a portrait of Logan, a bust of William Penn, a clock, a print of the Sortie of Gibraltar, and damaged some maps. The Directors wrote that “the destruction of an original portrait of James Logan…and a bust of the venerable Founder of Pennsylvania, is however, a subject of great regret to them.”1

They ordered an investigation of the blaze and recruited John Evans, a carpenter, to investigate. The fire started with the installation of a coal grate to replace a Franklin stove. It ignited what they thought was a brick pillar but was actually a wooden beam encased in a veneer of masonry. Evans reported that, “it appeared that the wooden Column which supported the clock case had been for many years enclosed in Brick work, put up originally to accommodate an open or Franklin stove– But a coal grate having been placed in lieu of the stove about three months since, in doing which it became necessary to cut away a part of the Brick-work adjoining the columns (which appeared to be solid masonry) and which must have covered the mortar in that part, say in each joint, the heat from the grate communicated to the column from time to time, until at length the Southern one became ignited, & the fire progressed & such an extent, that about one third of the Galleries, and the lining on the east side of the Room, with many valuable & scarce books were destroyed.”2After the column lit up, “the fire ran up the clock, and along the corridors.”3 Ironically, the Directors had removed the Franklin stove for a coal grate, because they thought it would be safer. “The fire originated in the breastwork of the chimney, from a grate recently fixed in the Loganian Library, with a view to the greater security afforded by coal fire.”4 Fortuitously, the fire occurred during a Directors’ meeting at the Library. “The presence of the Directors, at one of their state meetings, in an upper room…fortunately prevented any delay in the introduction of water.”5 The Library Company still has a set of six fire buckets, purchased in 1797, that may have been used.

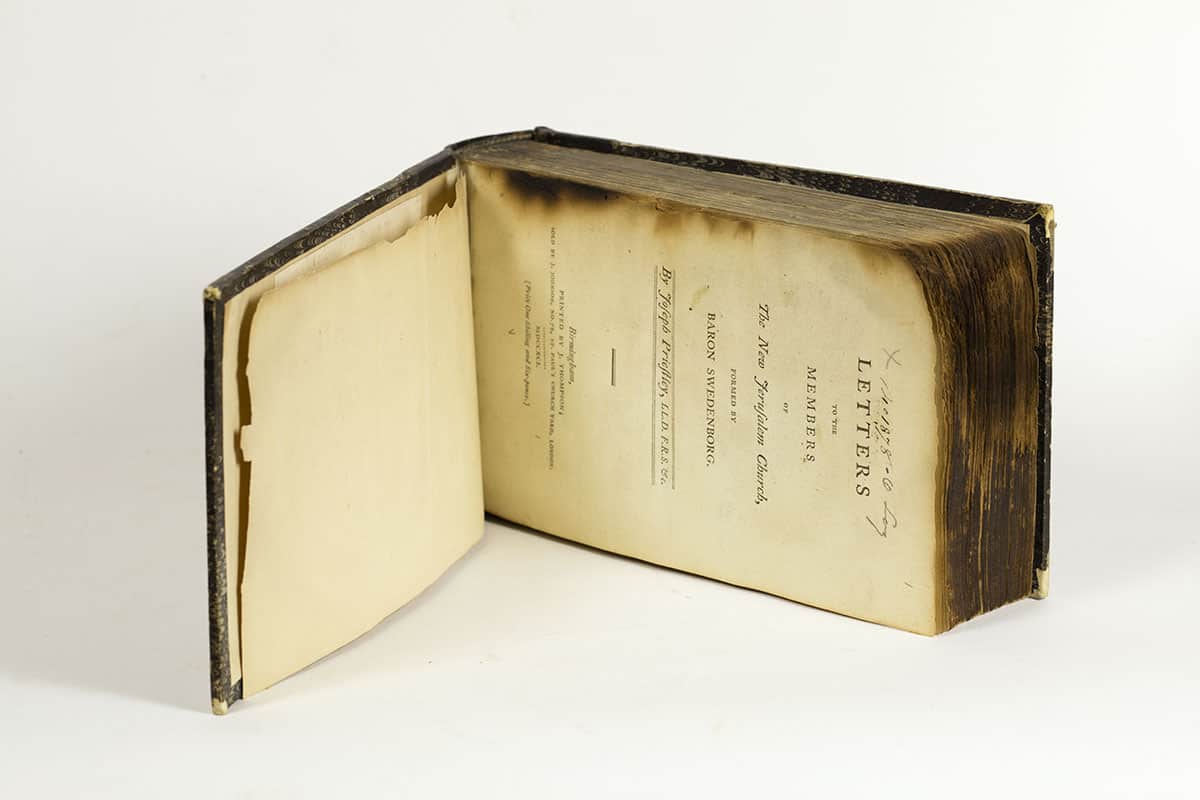

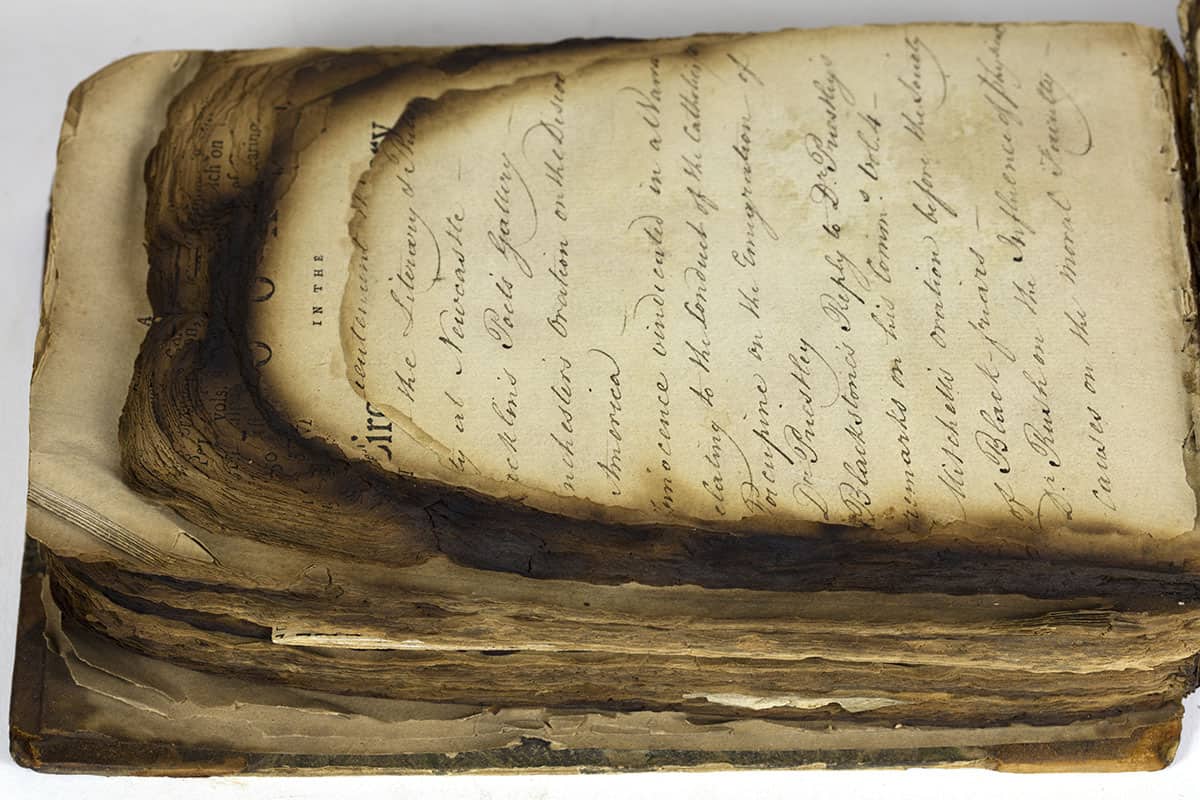

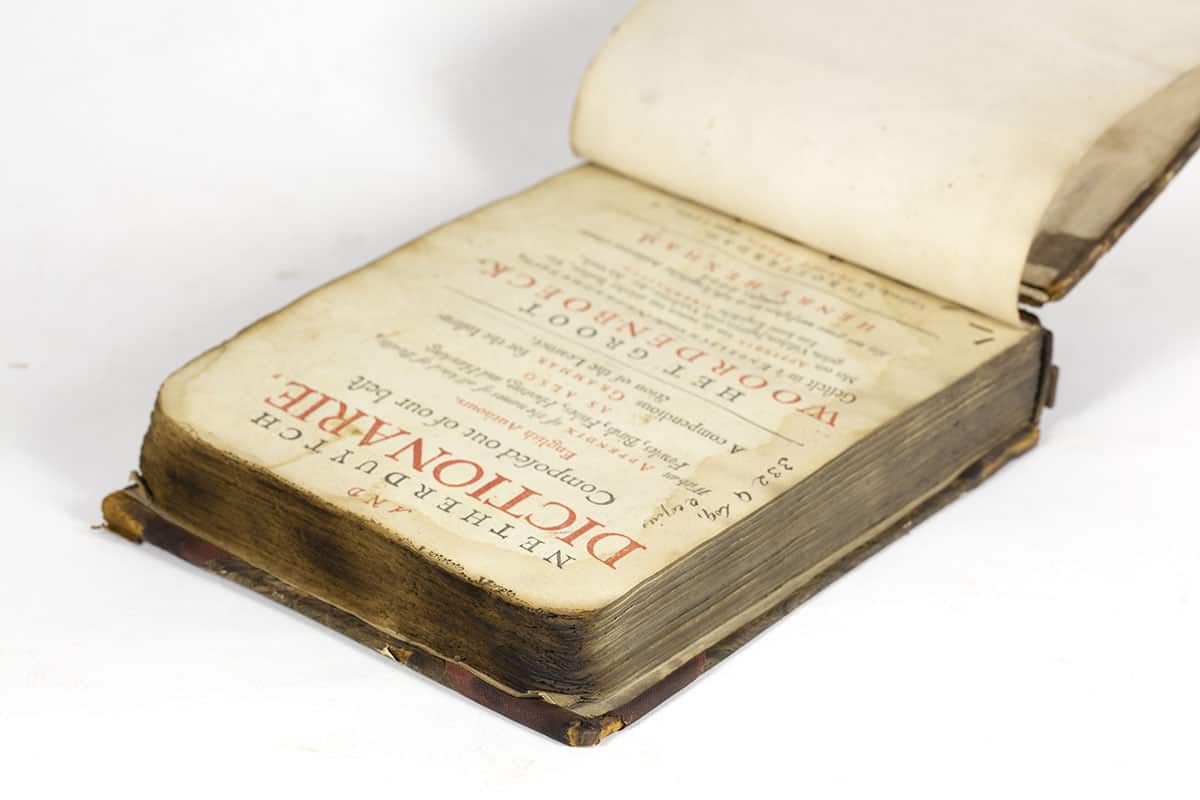

Additionally, the Directors’ meeting cleared Librarian John Jay Smith and enabled “them to exonerate their Librarian, and those employed by him, from any imputation of negligence.” Smith was the great-grandson of James Logan. He had the task of sorting through the mess with former Librarian George Campbell’s help.8 In total, 392 books were totally destroyed, 158 were repaired, and another 1,403 had to be rebound.9 These books had their binding removed and the damaged charred edges trimmed. Many had to be rebound horizontally. We have a number of examples of these titles.Also credited was the “prompt and energetic exertions of the Fire and Hose Companies, particularly the Pennsylvania and Fame, whose location enabled them to bring their powerful apparatus into almost immediate action, the preservation of the Library is chiefly attributable.”6 Both fire companies were housed in the lot adjacent to the Library Company on Fifth Street.7 These efforts stopped the progression of the fire and kept it contained, saving the Library Company and its collection.

The Library Company had another matter to deal with: its policy with the American Fire Insurance Company. A dispute over what items the policy covered needed to be resolved. The Library totaled its loss to $3,293.55. The insurance company objected to covering the following: “The Clock valued at $200, Damage to the Maps $25, Portrait of James Logan $100, Bust of William Penn $50, Print of Sortie of Gibraltar $20.” After reexamining the policy, the Library Company’s directors “were induced to give up the claim for the portrait of James Logan.”10 Horace Binney, a Library Company shareholder and noted lawyer, was asked to decide about the other objects. The argument hinged on what was covered by the term “&c.” Binney ultimately decided, “the Policy is on Books, Maps, &c; the latter Instrument being perfectly clear and a mere extension of orders…The words et caetera (&c) comprehend other things of the like kind with those before described, but not things similar. Manuscripts-which are not in the popular sense books — plans of buildings towns & forts which are not in the popular sense maps, would be included within the et caetera and things also less similar than these. But I am of opinion that the words do not include a Clock, nor any furniture of the Library, still less a Bust… The American Fire Insurance Company ought to pay to the Library Company the amount of damage to maps $25 and the value of the large print and plan of the Siege of Gibraltar $20 but that they ought not to pay for the clock or the Bust of William Penn. Signed H. Binney Feby 26, 1831.”11 In the end, the Library Company had to deal with a total cost of $3,540.64 of which the insurance covered $2,943.55. The Library had to absorb $350 for the loss of the bust, portrait, and clock and needed to pay another $247.09 for the labor in drying the books and paying appraisers.

Thanks to antiquarian John Fanning Watson, the original Logan portrait has been documented. In 1830, Watson asked to reproduce the portrait for his upcoming book, Annals of Philadelphia. The Library Company’s minutes record that “John F. Watson of Germantown desired the use for a few days of the portrait of James Logan for the purpose of copying the same to insert in his forthcoming annals of Philadelphia. The request was granted provided the portrait be not taken out of the Library building.”12 Watson noted in his book the origin of the illustration: “The engraved portrait is taken from a family piece now in the Loganian Library.”13

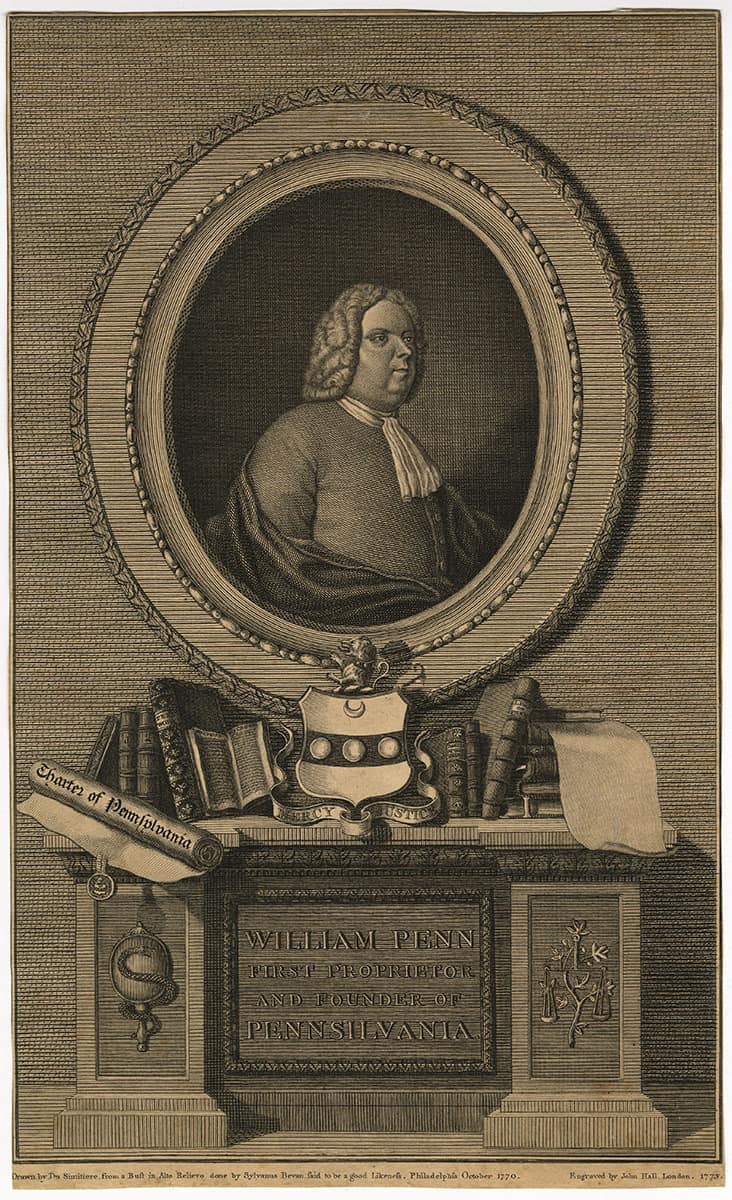

Likewise, Pierre Du Simitiere made a drawing in 1770 of the original bust of William Penn done by Sylvanus Bevan. John Hall used the drawing to engrave this image of Penn in 1773.

Unfortunately, there is no image of the clock, but an article in the Philadelphia Gazette the day after the fire describes it as being “made by a French artist, so constructed as to ring an alarum (sic) at the going down of the sun on every day of the year.” It further says that the “clock was the only one of the kind in the world.”14

Thomas Sully based his portrait on one by Gustavus Hesselius that James Logan’s descendant Deborah Logan held at their ancestral home Stenton. Deborah granted permission to the Library Company to borrow the portrait in April 1831 for the copying.15 This painting is now in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s Collection at the Philadelphia History Museum. As payment for the painting, Sully received two shares in the Library Company. Sully have one share to Ashbel G. Ralston, one of his fellow directors at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the second share to George D. Wetherill, who was a dealer in paints.16 James S. Earle (1807-1879) made the frame for the portrait. The Library paid him $6.50 for the frame and cleaning the borrowed portrait from Deborah Logan.17Earle, a restorer and frame maker, in partnership with Thomas Sully ran a commercial art gallery that sold paintings, prints, and mirrors, and operated from 1819 to at least 1846.18

The Library Company, through donations and purchases, replaced some of the other items destroyed in the fire. In 1833, John Jay Smith presented the Library with a bust of William Penn. The Library Company purchased a clock from John Child in 1835 for $125 that would chime at sundown, which was the Library’s closing time. But the print of Gibraltar does not seem to have been replaced as there is none in the collection currently.

Linda August

Curator of Art & Artifacts

Thomas Sully. James Logan, 1831. Oil on canvas. Commissioned by the Library Company, 1831.

Library Company Fire Bucket, 1797. Leather. Purchased by the Library Company, 1797.

Priestley, Joseph. Letters to the Members of the New Jerusalem Church. Birmingham: J. Thompson, 1791. Am 1791 Nic Log. 1878.O.1

Books in the Circulating Library at Leeds. Leeds: James Bowling, 1790. Am 1792 Win Log. 1849.O.1. This book has a number of pamphlets bound together. A large portion of the tops of the pamphlets have been burnt away.

Hexham, Henry. A Copious Englisg (sic) and Netherduytch Dictionarie. Rotterdam: Arnout Leers, 1660. Wing H 1650 (1)Log. 332.Q. The title page begins with the word And as the top of all the pages has been burnt off. Notice how all three books had to be bound horizontally.

Watson, John Fanning. Annals of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: E.L. Carey & A. Hart; G. & C.H. Carvill, 1830, engraving opposite p. 506.

John Child. Tall Case Clock, 1835. Pine. Purchased by the Library Company from John Child in 1835.

Hall, John, engraver. William Penn. London: Richard Penn, 1773.

1 Register of Pennsylvania, vol. 7, no. 3 (Jan. 15, 1831), p. 47.

2 Library Company Directors’ Minutes, vol. 5, April 7, 1831, p. 317-318.

3 Philadelphia Gazette and Daily Advertiser, vol. 54, no. 12,953 (Jan. 7, 1831).

4 Register of Pennsylvania, vol. 7, no. 3 (Jan. 15, 1831), p. 47.

5 Register of Pennsylvania, vol. 7, no. 3 (Jan. 15, 1831), p. 47.

6 Register of Pennsylvania, vol. 7, no. 3 (Jan. 15, 1831), p. 47.

7 Scharf, J. Thomas and Thompson Westcott. History of Philadelphia, 1609-1884. Philadelphia: L.H. Everts & Co., 1884, p. 1901-1902. In 1808, the directors of the Library Company granted to the Pennsylvania Fire Company the right to use the northwestern portion of a lot adjoining the Library. The Fame Hose Company was founded in 1818 and soon also obtained permission from the Library Company to use the adjacent lot, building their house next to the Pennsylvania Fire Company.

8 Library Company Driectors’ Minutes, vol. 5, January 7, 1831, p. 309.

9 Library Company Driectors’ Minutes, vol. 5, March 3, 1831, p. 315.

10 Library Company Driectors’ Minutes, vol. 5, March 3, 1831, p. 312-313.

11 Library Company Driectors’ Minutes, vol. 5, March 3, 1831, p. 314-315.

12 Library Company Directors’ Minutes, vol. 5, Apr. 1, 1830, p. 278.

13 Watson, John Fanning. Annals of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: E.L. Carey & A. Hart; G. & C.H. Carvill, 1830, p. 509.

14 Philadelphia Gazette and Daily Advertiser, vol. 54, no. 12,953 (Jan. 7, 1831).

15 Fisher, Sydney G. to George Abbot, July 1, 1899, letter bound in Library Company Directors’ Minutes, vol. 5, between p. 308-309.

16 Library Company Directors’ Minutes, vol. 5, November 3, 10, 1831, p. 330-331.

17 Loganian Library Minutes, vol. 1, November 10, 1831, p. 202-203.

18 Worcester Art Museum, Biography of Thomas Sully, http://www.worcesterart.org/collection/Early_American/Artists/sully/biography/ . The Library Company has the auction catalog of the sale of items in Sully & Earle’s Gallery in 1848. M Thomas & Sons. Catalogue of Valuable Paintings, Framed Engravings, Enamlled Stained Glass… Philadelphia: King & Baird, 1848. Am 1848 M Thomas 114805.O