Reader Spotlight: Zachary Schrag on the Native Flag

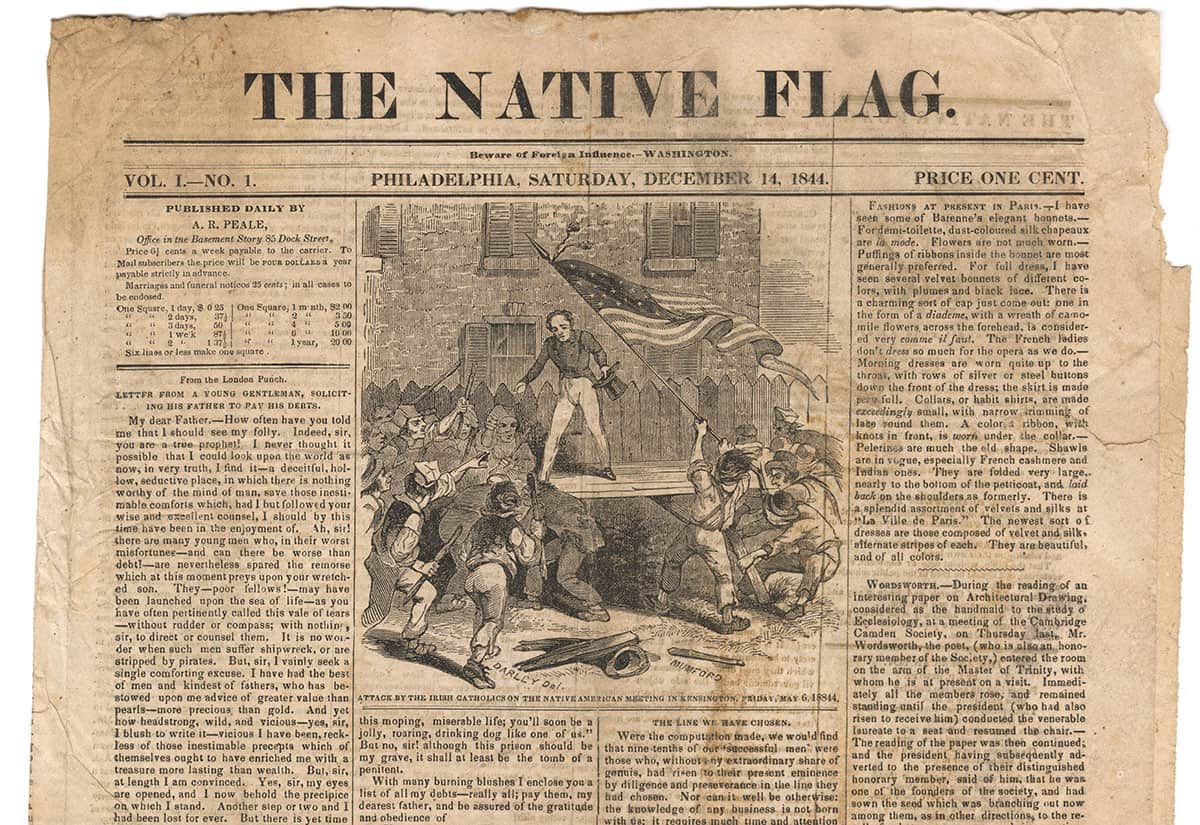

Detail from Vol. 1, no. 1 (December 14, 1844) of the Native Flag, a 2013 gift of Kenneth C. Trotter, Jr. Click on image for larger view.

In January 2019, Zachary M. Schrag, a professor in George Mason University’s Department of History and Art History, examined a range of 19th-century nativist material in the Library Company’s collections. One item in particular—an issue of a short-lived and little-known Philadelphia newspaper— proved especially relevant to his research. In the words of Prof. Schrag:

I was astonished to open the folder containing the Native Flag of December 14, 1844. The newspaper, especially its front-page engraving, offers new insight into how Philadelphia nativists understood themselves and their opponents in 1844, the year of the city’s nativist riots.

The newspaper was the first issue of what had been intended as a nativist penny daily published by Augustin Peale, grandson of Charles Willson Peale. As a 24-year-old ward leader in the Native American party, Augustin Peale had marched with other nativists on May 7, 1844, the second day of fighting between nativists and Irish immigrants in Kensington, which was then an independent district north of the city of Philadelphia. He was shot during the battle and lost his left arm to amputation that evening. By autumn Peale had recovered enough to seek and win office as county auditor on the Native American ticket, and in December he launched the Native Flag in part, he explained, because Philadelphia’s three existing nativist dailies (the Daily Sun, the Native American, and the American Advocate) had been insufficiently loyal to the party. Apparently he mistook the market. There’s no record that the Native Flag endured past its first issue, and the Library Company’s copy may be the only one extant.

While the text of the newspaper is fairly similar to what one might find in the other nativist papers, the Native Flag is remarkable for the engraving on its front page. Earlier in 1844, illustrators had produced woodcuts, lithographs, and engravings depicting the fighting in Kensington, the burning of the churches, the deployment of the Pennsylvania Militia, and scenes of tourists visiting the burned-out churches and Kensington market house. William and Frederick Langenheim even captured curious crowds in an 1844 daguerreotype which is possibly America’s first news photograph. Some of these artists seem to have aimed for a dispassionate record of events, while others sought to persuade. John Magee’s lithograph Death of George Shifler in Kensington, for instance, is a pietà, depicting the young nativist clutching the American flag he was allegedly defending when shot down by treacherous Irishmen.

For the most part, these images have two things in common. First, they depict the events of May 6 or later, either the most spectacular violence or its aftermath. Second, while they may foreground nativists or militiamen, most confine Irish immigrants to the background, presenting them as indistinct members of a mob or as shadowy snipers firing from second-story windows.

The Native Flag engraving is different. Drawn by “Darley”—probably Philadelphia-born Felix O. C. Darley (1822-1888), who would later become one of America’s most renowned illustrators—it shows neither the “Three Days of May” (May 6-8) that comprised the worst violence, nor the ruins that attracted other illustrators. Instead, Darley shows an earlier rally, which took place in Kensington on Friday, May 3. Hoping to build their new party, nativists erected a crude stage in a vacant lot in Kensington’s Third Ward. As they delivered speeches condemning immigrant power and the Catholic Church, hecklers shouted, “Down with the stage!” and “Down with the bastards!” Despite their verbal aggression, they gave the nativists the chance to jump off the stage, and even helped one elderly speaker down before disassembling the platform. Rather than fight, the nativists retreated to a nearby Temperance Hall.

In addition to showing an event neglected in other renderings, the Darley illustration gives a much more distinct view of nativists’ impressions of Irish Americans, featuring them prominently in the foreground and depicting individual bodies and faces. Darley’s Irishmen outnumber the speaker, eighteen to one, signifying the threat to the native-born of a flood of immigrants. They are crude in both dress and behavior. Unlike the American gentleman, properly dressed in a tailcoat, the Irish auditors wear ragged trousers and shirtsleeves, the latter rolled up for a fight. Most carry clubs, which nativists would likely identify as shillelaghs, markers of Irish identity. While one tears down the American flag, others prepare to pull the platform out from under the nativist speaker.

Yet for all of this, Darley does not present the Irish as racially inferior, or even racially distinct. As Perry Curtis and Dale Knobel have shown, at the time of the riots, nativists had not yet embraced the racial stereotypes that would define anti-Irish imagery in later decades. Darley’s Irishmen have long sideburns, but they lack the tiny noses, long upper lips, and jutting jaws that later generations of illustrators used to make Irish men and women appear simian. (The figure in profile at the far left of the Darley illustration is arguably more in line with these later stereotypes.)

So while Darley depicts Irishmen as violent, uncouth, and prone to mob action, he does not present them as irredeemably subhuman. Perhaps he took seriously the nativist claims that they did not want to halt immigration or even deny citizenship to immigrants, but only extend the period of naturalization to twenty-one years, long enough for Irish and other arrivals to become fully acclimated to American political traditions. Few immigrants or Catholics accepted this program, but by the time the Native Flag appeared in print, enough Philadelphia voters had been persuaded of the nativist worldview that Peale and other nativists had won their elections and were preparing to take power. While Darley’s engraving reminds readers of the supposed perils of foreign influence, it also boasts that native, Protestant eloquence could overcome Irish Catholic force.

Professor Schrag is currently working on a book on the Philadelphia nativist riots of 1844; he is also the author of this essay: https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/nativist-riots-of-1844/