Reader Spotlight: Robert Eskind on 19th-Century Maps of Santo Domingo

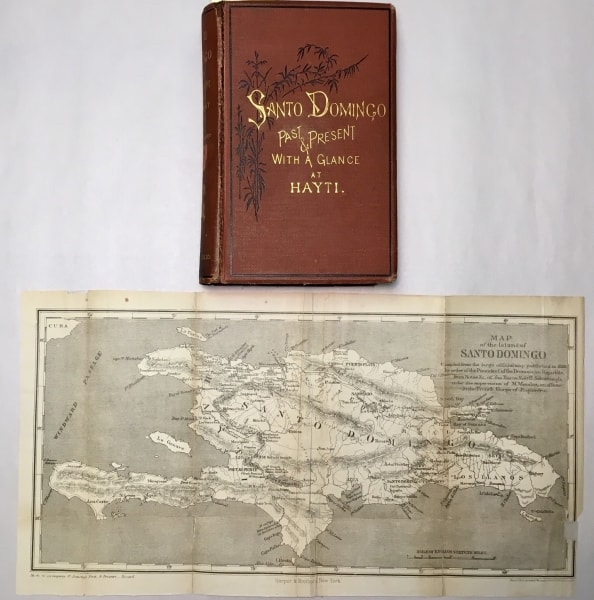

Front cover and map from Samuel Hazard’s Santo Domingo, Past and Present: With a Glance at Hayti (1873).

For the past several months, I have been tracing the history and afterlife of Schomburgk’s map of the Dominican Republic. Sir Robert H. Schomburgk (1804-1865), already famous for his explorations in British Guiana, was the British Consul in the Dominican Republic from 1849 to 1857. His map of the island, first published in Paris in 1858, was reproduced for the next twenty-five years in the kind of reduced and simplified form that appears in Samuel Hazard’s popular book about Santo Domingo—a map the Library Company conserved recently. Note that the Paris 1858 map measures roughly four times the size of the map in Hazard’s Santo Domingo, Past and Present; With a Glance at Hayti (1873), and has been digitized by the Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/2012590217/

Even in its reduced form, the Schomburgk map was put to work in the promotion of mining, settlement, and annexation projects from the 1860s to the 1880s. In Joseph Warren Fabens’ Facts about Santo Domingo, Applicable to the present Crisis: An Address Delivered before the American Geographical Society at New York, April 8, 1862 (1862), the words “Copper Region” and “Copper and Gold” and “Coal” were helpfully imprinted onto the cleared out topography, so that investors would know what to look for. Fabens was a partner to William Lesley Cazneau and Jane McManus Cazneau in a copper mining venture, a proposal to settle freedmen in Santo Domingo (as agricultural laborers), proposals to colonize the island with white Americans, and the acquisition of Samana Bay as a strategically important naval coaling station and real estate venture. Fabens and the Cazneaus were instrumental in shaping American policy towards the island from the administration of Franklin Pierce to that of Ulysses S. Grant.

President Grant was in favor of the annexation of the Dominican Republic (and Haiti, too) as an American territory, but found it a hard sell in the United States Senate. As a compromise, a commission of inquiry on Santo Domingo was dispatched to the island in 1871 to survey the island’s natural resources, gauge Dominican public opinion, explore the question of Dominican racial character, and look at the books (how much public debt would the United States assume in the event of annexation). Their published Report of the Commission of Inquiry (1871) was an unvarnished appeal for annexation. It was illustrated with the same Schomburgk map, but with the “Copper and Gold Region” tags discreetly removed.

Samuel Hazard (1834-1876), a Philadelphia bookseller who rose to Brevet Major in the Civil War, was one of the large party that accompanied the Commission (thirty-two names—including journalists from New York, Philadelphia and Ohio—are listed in the Report). His presence was partly official: he accompanied one of the Commissioners, and co-authored a “Report upon the River Yaque” for the Report. The previous year, Hazard finished Cuba with Pen and Pencil—an account of his casual wanderings on the island, illustrated with his sketches, acquired prints, and photographs (rendered as illustrations). His travels with the Commission led to the publication in 1873 of Santo Domingo, Past and Present: With a Glance at Hayti. It was produced with a similar breezy style and well-illustrated with lithographed plates, in-text wood engravings, and the folding map which he quite rightly attributes to Schomburgk. (In both Fabens’s pamphlet and the Commission’s official report, Schomburgk’s name does not appear.) Despite the racism and expansionist assumptions underlying Hazard’s text, Santo Domingo, Past and Present has enjoyed a remarkably successful afterlife, being republished in Spanish editions in the Dominican Republic and Venezuela. (See Candelario, Black behind the Ears p. 54-57.)

The Schomburgk map in its reduced form, as used by Hazard and others, is distinguished by the absence of the place names with which the 1858 map abounds. With the vast reduction in size, there is simply no room for the hundreds of topographical and cultural features that populate the larger map. The complex network of mountains that rumple the 1858 map are reduced to three contiguous chains, yielding great clarity and broad unbroken plains that misrepresent the character of the landscape. But the reduced map is not detailed enough or of a scale to be useful in practical wayfaring or orienteering. In the absence of settlements, historical sites and intermediate mountains, there is vacant land, like the famously underpopulated Dominican Republic itself, welcoming the projection of human desires—copper and gold regions, plantations, railroad concessions—American enterprise. While I am still not entirely sure what purpose Schomburgk intended for his map, I doubt that it was intended to promote American schemes of exploitation such as Hazard’s Santo Domingo, Past and Present. And the tattered shape of the Library Company’s copy suggests that the book appealed to Philadelphians—who unfolded and folded the map until it fell apart along the fold lines—mute testimony of the book’s appeal to readers.

By Library Company member Robert Eskind; Mr. Eskind is currently working on a book manuscript titled: “This Wretched Business”: Economic Geology in the Dominican Republic, 1905-1916—which will examine the work of Philadelphia mining engineer F. Lynwood Garrison.