The Norris Family and Their Networks

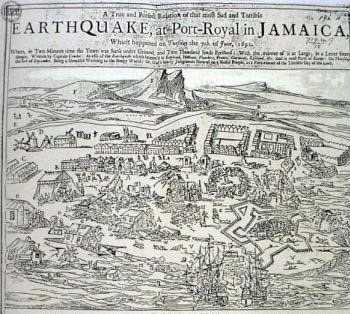

In 1690, a young Quaker named Isaac Norris (1671-1735) arrived in Philadelphia to explore a possible move for his family, who lived in Jamaica. Young Isaac took a couple of years to acquaint himself with the city’s prospects, and returned to Jamaica in 1692, only to find that his father and most other members of the family had perished in the Port Royal earthquake of that year and its disastrous aftermath.[2] One can only imagine his state of mind upon learning of his family’s demise. He determined that his future lay in Philadelphia, and so returned in 1693 with about 100 pounds (approximately $25,603) to his name.[3]

Norris’s modest financial resources were supplemented by his intellectual ability, business talent and ambition. His mercantile business proved to be profitable, and he became a friend and strong ally of William Penn, even serving as his interlocutor in settling some of Penn’s debts in England. His business and political activities brought about his election to the Pennsylvania colonial assembly, and he eventually became its Speaker. He also served as a justice of the Courts of Philadelphia, and was elected Mayor of Philadelphia in 1724.[4]

His 1694 marriage to Mary Lloyd (1674-1748), the daughter of the Deputy Governor of Pennsylvania, also proved fruitful: together, they had 14 children, three of whom became Library Company (LCP) shareholders, the earliest in 1734. Children of these three also became shareholders, as did some of their descendants. In subsequent years, Norris shares were passed vertically and collaterally within the family, and Norris descendants even purchased new shares. At least one LCP share (64) remained in the Norris family for 200 years.

This month’s Share Profile will explore the Norris LCP Share universe, focusing on those who worked to make their contemporaries and the city healthier, while they shaped health care and medical education in Philadelphia. Our journey will also give us an opportunity to appreciate the contributions of multiple Library Company shareholders and in doing so, honor all those who are continuing to care for Philadelphians during this fraught time.

Be forewarned: this is a multi-mile perambulation requiring good walking shoes. Please join us for this wide-ranging and multi-generational ramble!

The Norris Brothers and The Founding of Pennsylvania Hospital

In early 1751, the Pennsylvania colonial assembly enacted a measure encouraging the establishment of a hospital in the city of Philadelphia. The act was in response to a group of Philadelphians who stated that they

had frequent Opportunities of observing the Distress of such distemper’d Poor as from Time to Time came to Philadelphia, for the Advice and Assistance of the Physicians and Surgeons of that City. . . and how expensive the Providing good and careful Nurses, and other Attendants, for want whereof, many must suffer greatly, and some probably perish, that might otherwise have been restored to Health and Comfort, and become useful to themselves, their Families, and the Publick, for many Years after; and considering moreover, that even the poor Inhabitants of this City, tho’ they had Homes, yet were therein but badly accommodated in Sickness, and could not be so well and so easily taken Care of in their separate Habitations, as they might be in one convenient House, under one Inspection, and in the Hands of skillful Practitioners; and several of the Inhabitants of the Province, who unhappily became disorder’d in their Senses, wander’d about, to the Terror of Their Neighbours, there being no Place (except the House of Correction) in which they might be confined. . . and that this House was by no Means fitted for such purposes; did charitably consult together, and confer with their Friends and Acquaintances, on the best Means of relieving the Distressed, . . . . and an Infirmary, or Hospital, in the Manner of several lately established in Great Britain, being proposed, was so generally approved, that there was Reason to expect a considerable Subscription from the Inhabitants of this City, toward the Support of such an Hospital. . . . .[5]

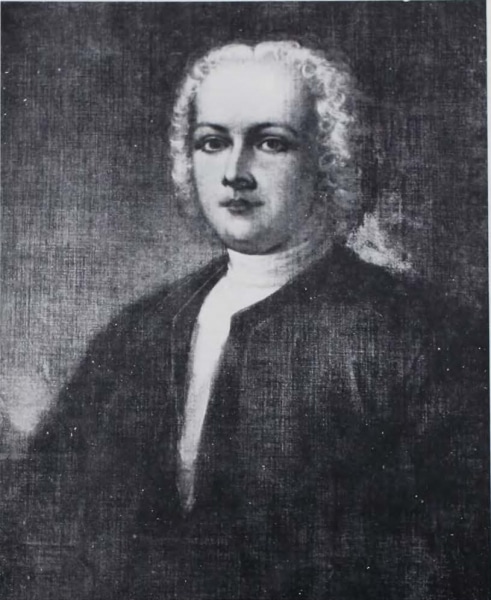

One of the forward-looking supporters to be on the first Board of Managers for the proposed hospital was, not surprisingly, Benjamin Franklin, who had been recruited by Dr. Thomas Bond (1713-1784, LCP Share 21). Dr. Bond was the first to introduce the idea of a hospital to Philadelphia’s intellectual and cultural circles, but he soon learned that Franklin’s endorsement would be crucial to the effort.[6] Franklin and Bond were aided by a host of other civic and health-minded Philadelphians who were also LCP shareholders, among them two sons of the above-mentioned Isaac Norris and Mary Lloyd: Isaac Norris (1701-1766, named for his father) and his younger brother, Charles (1712-1766).

Isaac Norris II

Isaac Norris II (LCP Share 64), had followed in his father’s footsteps, pursuing mercantile and political interests. He was a member of the Philadelphia Common Council, then voted into the Pennsylvania Assembly, and in 1751 became Speaker, a position he would hold until 1764. Isaac was a substantial subscriber to the hospital and helped Franklin to ease the proposal’s way through the Assembly. His brother, Charles Norris (a subsequent holder of LCP Share 64), was also a successful Philadelphia merchant and a Trustee of the Pennsylvania General Loan Office, as well as a member of the hospital’s first Board of Managers. When issues arose between the hospital petitioners and the Pennsylvania Proprietors (Thomas and Richard Penn), Charles Norris assisted with the negotiations.[8] He also carried some weight with the Pennsylvania Assembly, and in 1754 was appointed Keeper of the Assembly Library.[9]

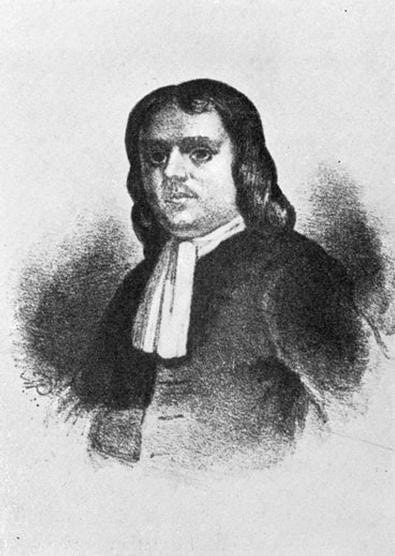

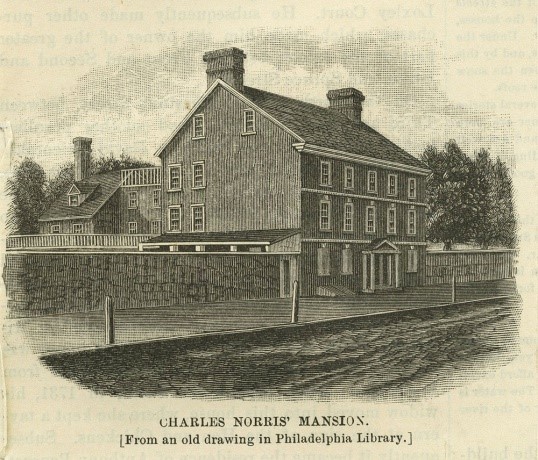

Charles Norris (1712-1766)

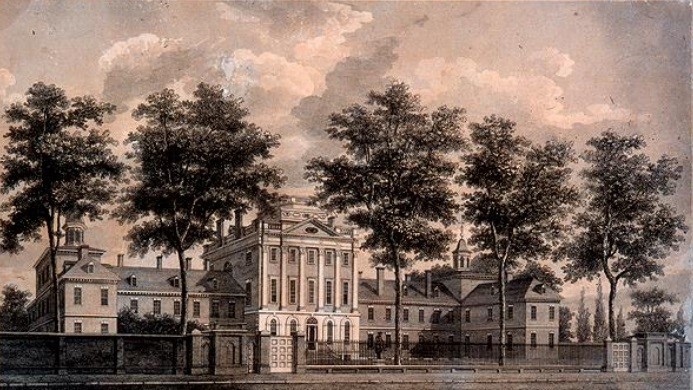

Charles Norris Mansion, Erected in 1750, Located on Chestnut between 4th and 5th Streets

As subscriptions to the hospital grew during 1751-1752, the Board of Managers developed and approved rules of administration, assembled a medical staff, hired an apothecary, and found a temporary location for the hospital at 7th St. and Market St. (south side). Charles Norris continued on the Board of Managers and became Treasurer. According to Benjamin Franklin’s 1754 report, between February 1752 and April 1754, the hospital admitted 117 patients, 60 of whom were classified as “Cured.”[12] In that same year, the managers were able to purchase land for a site at 8th St. and Pine, and in December 1756, Pennsylvania Hospital moved into its permanent home, a living testament to what a networked community could do.

Pennsylvania Hospital

The establishment of the hospital paralleled the development of Philadelphia’s first institution of higher education, the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania), which was chartered as a college in 1755, and initially located at 4th Street and Arch. It was Benjamin Franklin’s Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth that set out the principles upon which this new institution was to be based. One of the original Trustees for the College was Dr. Thomas Bond. In 1765, at the recommendation of Dr. John Morgan (1735-1789, presumed LCP Share 285), who had once served as Apothecary at Pennsylvania Hospital , the College established a separate medical department and curriculum. Dr. William Shippen (1736-1808, LCP Share 43), who had also once been Apothecary at the hospital and had launched the first lectures on anatomy in Philadelphia, was named Professor of Anatomy. Attendance at the Pennsylvania Hospital for one year became a core requirement for the Bachelor of Medicine degree, and in 1768, Dr. Bond became the Chair of Clinical Medicine at the new medical school.[14]

Dr. Thomas Bond (circa 1770)

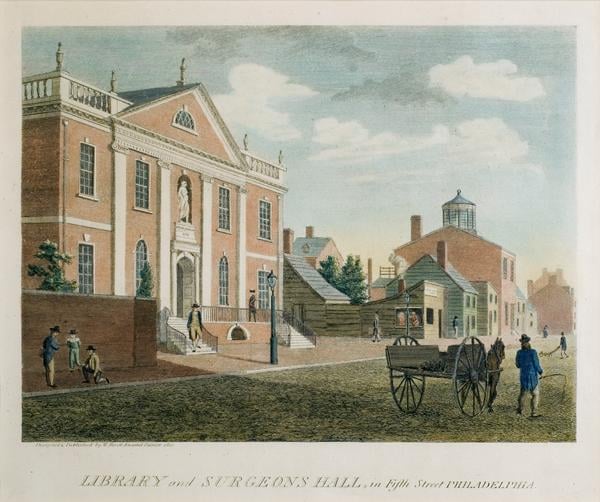

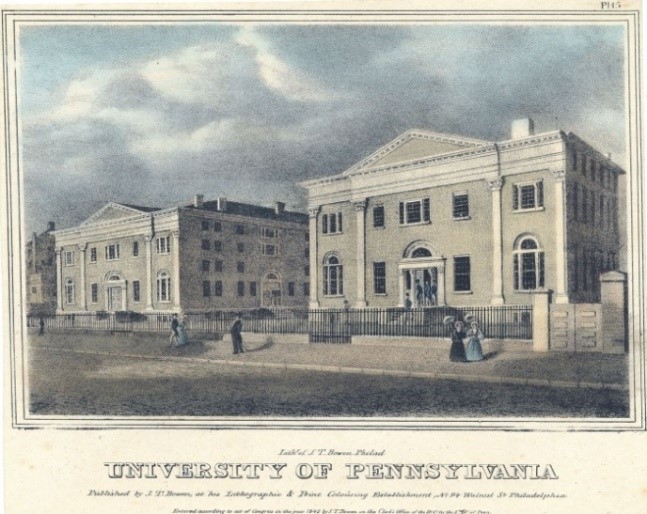

The close relationship between the nation’s first chartered hospital and its first medical school was aided by their proximity.[16] In the medical school’s early years, lectures were given in Surgeons’ Hall, between Chestnut and Walnut on 5th St. In 1801, the University erected two new buildings at 9th St. and Chestnut, one for the School of Arts and Sciences and the other for the Medical Department, as it was then called. Pennsylvania Hospital continued to serve as a clinical teaching site.

Library and Surgeons Hall (right background), Original Site of the University of Pennsylvania’s Medical School

Second Home of University of Pennsylvania Medical School, 9th St. and Chestnut

George Washington Norris, MD (1808-1875, LCP Share 1051)

It was in the medical school’s new building and Pennsylvania Hospital that another Norris family member and LCP Shareholder received his training as a physician. George Washington Norris was Charles Norris’s grandson. He received his Bachelor’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1827, and went on to pursue his medical degree, completing the course of study in 1830. His preceptor was Dr. Joseph Parrish (LCP Share 322), a highly respected physician and medical author. Norris wrote his doctoral thesis (a degree requirement in those days) on smallpox and other vaccine diseases, a topic with which he was intimately and sadly acquainted. He and a number of his classmates had survived the disease when it surged in the late 1820s, but his older brother, Thomas Lloyd Norris, was not so fortunate, dying in 1828 despite having been vaccinated as a child. George Norris would go on to study in Europe and then return home to Philadelphia, where he joined the surgical practice at Pennsylvania Hospital, practicing there for 27 years. He became the Chair of Clinical Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School, and eventually, a Trustee of the University.[19]

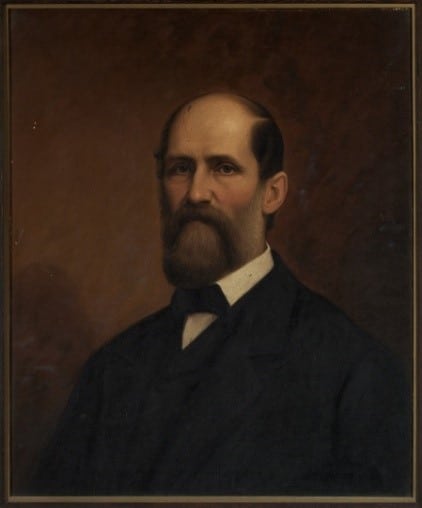

Two Views of George Washington Norris, 1808-1875

Norris was remembered by colleagues for his insistence on clean and flexible bandages and frequent hand-washing. His calls for “more soap and water” at the bedside were apparently a defining and unforgettable characteristic.[21] He published multiple medical articles, most of which dealt with fractures (his surgical specialty), as well as a history of early medicine in Philadelphia. He served as Vice-President of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, President of the Board of Managers at Children’s Hospital, and a director of the Library Company, and was a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences, the American Philosophical Society, and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.[22] His marriage to Mary Fisher in 1838 enlarged the Norris clan by two: a son, William Fisher Norris and a daughter, Mary Fisher Norris.

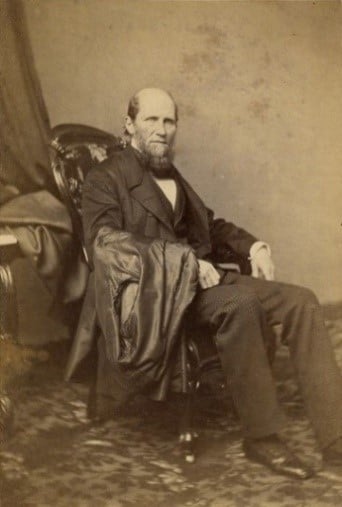

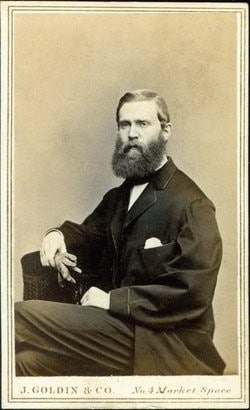

William Fisher Norris (1839-1901) William Fisher Norris inherited his father’s LCP share and continued the Norris medical legacy, graduating from the University of Pennsylvania with a medical degree in 1861. He completed a residency at Pennsylvania Hospital, and then enlisted in the army, receiving an appointment as an assistant surgeon. He was put in charge of Douglas Hospital in Washington D.C., where he served until October 1865. While at Douglas, he tended the wounded on-site at Gettysburg, and he and Dr. William Thomson, a Jefferson Medical School graduate (1833-1907, Share 171), sought to improve healing practices by taking photographs of wounds and fractures to document treatment. The Surgeon-General’s office and Army Medical Museum recognized the value of this innovation, which further inspired Thomson and Norris to experiment and succeed in photographing microscopic sections (photomicrographs), a further advance in medical science.[23]

Following the Civil War, William went to Europe for additional study. His father had spent most of his post-graduate medical training in France, but William chose Vienna in order to study with physicians prominent in eye surgery and treatment of eye diseases. He returned to Philadelphia in 1870, and practiced at Wills’ Eye Hospital. In 1873, he was made a Lecturer in the young field of ophthalmology at the Medical Department of the University of Pennsylvania. In 1876, the University created a Professorship in Ophthalmology, to which Norris was appointed. He went on to author or co-author textbooks and multiple articles in ophthalmology.[24] Together with colleagues at Jefferson, including William Thomson, with whom he had collaborated during the Civil War, he helped to establish ophthalmology as a recognized medical specialty in America.[25]

William Fisher Norris (1839-1901)

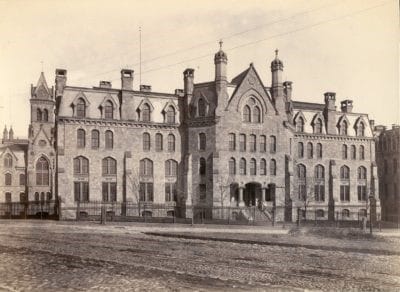

Norris’s professional advancement coincided with large-scale changes in Philadelphia health care and medical education. While Norris was in Europe, the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) developed plans to move its campus to West Philadelphia, which it did in 1871. The College of Arts and Sciences moved first, followed by the Medical Department, as the School of Medicine was still called. Because some medical student hospital training sites were now at some distance from the Medical Department, the University also had to plan for the construction of a teaching hospital close to its new home.[27]

Third Home of the University of Pennsylvania Medical Department,

Medical Hall in West Philadelphia (later Logan Hall, now Claudia Cohen Hall), circa 1890

In collaboration with future Penn Provost Dr. William Pepper (1843-1898, LCP Share 593) and other Penn luminaries such as Dr. George B. Wood (1797-1879, LCP Share 735) and his nephew, Horatio C. Wood (1841-1920, LCP Share 760), Norris helped with the planning and fundraising for the nation’s first teaching hospital, University Hospital, now known as the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP). While the indefatigable Dr. Pepper raised funds from the city and the state as well as private sources, Norris served as Secretary to the fundraising committee, a role similar to that played by his great-grandfather Charles Norris during the planning and development of Pennsylvania Hospital.[29] He subsequently became President of the University Hospital Board of Managers, a position he held at the time of his unexpected death in 1901. He was also a Fellow of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences, and Vice President of the Philadelphia Pathological Society.

University Hospital, Original Building (1888)

Amid the intense professional activity of the 1870s, in 1873, William Fisher Norris found time to return to Vienna to marry Rosa Clara Buchmann (1848-1897), whom he brought back to Philadelphia. They had three children, George William Norris (1875-1965, LCP Share 781), William Felix Norris (1879-1925, LCP Share 1051) and Lloyd Buchmann Norris, who died as a child.

George William Norris (1875-1965, LCP Share 781)[31] continued the Norris’s medical line, receiving his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1899. He then became a resident physician at Pennsylvania Hospital. In 1911, he enlisted in the Medical Reserve Corps, and in 1916, as World War I preparedness efforts grew in the city, he collaborated with colleagues at the hospital to assemble staff for a Red Cross base hospital in France in response to the U.S. Army’s national call for medical, nursing and support staff for base hospitals in case of entry into the war.[32]

The base hospital system was the inspired idea of Dr. George Crile (Lakeside Hospital, Cleveland) who had taken a surgical team to work at the American Hospital in Neuilly-sur-Seine prior to American entrance into the war. Dr. Crile suggested to the Medical Department of the U.S. Army that each medical school and major U.S. hospital put together a unit of essential medical personnel and staff that could mobilize quickly if America joined the conflict. The Surgeon General endorsed the plan, and authorized Dr. Crile, Dr. Harvey Cushing (Harvard Medical School) and Dr. J.M. Swann (Mount Sinai Hospital, New York) to organize the first units. Because the U.S. still assumed a stance of neutrality at the time, the Red Cross became involved in the preparation effort, hence the units created were initially designated as Red Cross base hospitals. Thirty-three base hospital units were assembled from the staffs of American medical schools or hospitals. In addition to Pennsylvania Hospital, units were organized at Penn’s University Hospital (Base Hospital 20), Jefferson Hospital (Base Hospital 38) and Episcopal Hospital (Base Hospital 34).[33] Many more base hospitals would follow, organized by the Medical Department of the United States Army.

Colonel George William Norris at Pennsylvania Hospital

In Philadelphia, local recruitment efforts were highly successful, and the Pennsylvania Hospital Unit (Base Hospital #10) departed Philadelphia on May 18, 1917, bound for a hospital serving the British forces at Le Treport, France.

Pennsylvania Hospital Base Hospital 10, Departing Philadelphia May 18, 1917

George Norris served at Le Treport until late April 1918, when he was transferred to a hospital at Neufchateau, returning home in December 1918. In 1920, Norris received a citation from General Pershing for his “exceptionally meritorious and conspicuous services” as Senior Medical Consultant in the Toul Sector of the war.[36] Excerpts from Norris’s scrapbooks from World War I can be viewed on-line at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia website here: https://www.cppdigitallibrary.org/exhibits/show/great-war-physician

After the war, Norris resumed teaching as a professor of clinical medicine at University of Pennsylvania and serving as Chief of Clinical Medicine at Pennsylvania Hospital. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1922, and was also a member of the College of Physicians, the Historical Society, and the Academy of Natural Sciences. He was the author of numerous medical articles and several books, with a focus on principles of physical diagnosis and the importance of blood pressure measurement in disease management. He retired from medical practice in 1931, and spent his remaining years traveling, engaging in landscape photography and assembling family history.[37] He passed away in 1965.

The Norris Network Across Generations

Our whirlwind journey has taken us from the destruction of Port Royal in 1692 to the mid-20th century, through the founding and growth of some of Philadelphia’s best-known institutions, the development of the modern medical profession, and years beyond one of the world’s worst conflagrations. During their respective times, each generation of Norris family LCP Shareholders helped to build or support networks and institutions that connected their community, their city and their nation, advancing all three in the process. The Library Company thanks all those in every occupation who by their efforts continue to move us forward, especially during this most challenging period.

Claudia Siegel

Library Company of Philadelphia Volunteer

[1] Cundall F, The Governors of Jamaica in the Seventeenth Century (The West India Company, 1936), p. 134A, reprinted from a broadside in the British Museum. University of Florida Digital Collections, George A. Smathers Libraries, Digital Library of the Caribbean (dLOC), http://www.dloc.com, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00074120/00001/185j#template, accessed 5/28/2020.

[2] Isaac Norris was the youngest son of Thomas and Mary Moore Norris, who had moved to Jamaica from England around 1678, when they found persistent religious persecution of Quakers to be unbearable.. Jordan J. Colonial and Revolutionary Families of Pennsylvania (Genealogical Publishing Co., 2004), p. 82. Google Books, accessed 5/13/20.

[3] Nye E, Pounds Sterling to Dollars: Historical Conversion of Currency, https://www.uwyo.edu/numimage/currency.htm, accessed, 5/13/2020 .

[4] Jordan J, Colonial and Revolutionary Families of Pennsylvania, p. 82.

[5] “Some Account of the Pennsylvania Hospital, [28 May 1754],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-05-02-0089 [Original source: The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 5, July 1, 1753, through March 31, 1755, ed. Leonard W. Labaree. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1962, pp. 283–330.], accessed 5/9/2020.

[6] Bigelow J, ed., Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin (J.B. Lippincott & Co. Philadelphia, 1868), pp. 281-284, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433082363858, accessed 5/16/2020.

[7] Pennsylvania House of Representatives, House Speaker Biographies, image courtesy of the University Archives at the University of Pennsylvania, https://www.legis.state.pa.us/cfdocs/legis/SpeakerBios/SpeakerBio.cfm?id=114 accessed 5/16/2020.

[8] Morton T and Woodbury F, The History of the Pennsylvania Hospital, 1751-1895 (Philadelphia, Times Printing House, 1895), p. 34. For an enlightening discussion of the deeper politics behind the establishment of the hospital and the College of Philadelphia, see Jessica Chopin Roney’s Governed by a Spirit of Opposition: The Origins of American Political Practice in Colonial Philadelphia (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014), pp. 91-103.

[9] See “History of the State Library,” https://www.statelibrary.pa.gov/Pages/History-of-the-State-Library.aspx, accessed 5/24/2020.

[10] Portrait of Charles Norris, reprinted in Parsons W, “‘Orders What’s To Be Done At The Plantation’: The Isaac Norris Farm Accounts, 1713-1734,” Pennsylvania Folklife, Vol. 27,#1, p. 11, https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1075&context=pafolklifemag accessed 5/26/2020, original portrait from Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

[11] Castner, Samuel, Jr., 1843-1929 – Compiler, Norris, Charles, 1712-1766. Charles Norris’ Mansion.. Scrapbooks. Free Library of Philadelphia: Philadelphia, PA. https://libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/item/40455, accessed 5/24/2020.

[12] Franklin B and Hall D, “Some Account of the Pennsylvania Hospital. . .”

[13] Benjamin Franklin Historical Society, http://www.benjamin-franklin-history.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Pennsylvania-Hospital-1751.jpg, accessed 5/14/2020.

[14] Medical Faculty of the University of Pennsylvania, “Medical Department of the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, n.p., 1841), pp. 6-9, https://archives.upenn.edu/digitized-resources/docs-pubs/medical-dept-u-of-pa-1841, accessed 5/18/2020. In addition to the Bachelor of Medicine, the College Medical Department also offered a Doctor of Medicine degree, which required the recipient to complete and defend a thesis.

[15] Thomas Bond (1712-1784) portrait painting (ca. 1770). Retrieved from https://library.artstor.org/asset/SS37618_37618_40241408, accessed 5/26/2020.

[16] It should be noted that the Philadelphia Almshouse erected in 1732 had a hospital section, but it was not chartered as a hospital. In future years, this section became Philadelphia General Hospital. See Lawrence C, History of the Philadelphia Almshouses and Hospitals from the Beginning of the Eighteenth to the Ending of the Nineteenth Centuries, Covering a Period of Nearly Two-Hundred Years, (Philadelphia, 1905), p. 20., Google Books, accessed 5/19/2020.

[17] Birch W, “Library and Surgeons Hall, Fifth Street, Philadelphia,” (R. Campbell and Company, Philadelphia, 1799), from the Library Company of Philadelphia, https://digital.librarycompany.org/islandora/object/digitool%3A37984?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=4021e57bfae2353d1593&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=0&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=0, accessed 5/26/2020.

[18] Views of Philadelphia, and Its Vicinity (J.C. Wild & J.B. Chevalier, Lithographers, 1838), Plate 15, reissued by J.T. Bowen, https://digital.librarycompany.org/islandora/object/digitool%3A65359, accessed 5/24/2020.

[19] Hunt W, “Memoir of Dr. George Norris,” Transactions of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, Third Series, Vol. 2 (Collins, 1876), pp. xxxi-xxxiii, Google Books, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Transactions_studies_of_the_College_of_P/qfM-icX7FGQC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Memoir+of+Dr.+George+washington+Norris+college+of+physicians&pg=PR30&printsec=frontcover, accessed 5/18/2020.

[20] The first portrait is from the Library Company of Philadelphia, https://digital.librarycompany.org/islandora/search/dc.subject:%22Norris%2C%20George%20W.%20%28George%20Washington%29%2C%201808-1875%20–%20Portraits.%22?cp=islandora:root, accessed 5/18/2020; the carte de visite portrait can be found at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/63856403/george-washington-norris#view-photo=145637999, accessed 5/18/2020.

[21] Hunt W, “Memoir of Dr. George Norris,” Transactions of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, p. xxxiv.

[22] Hunt, ibid., p. xli.

[23] Risley S, “Dr. William Fisher Norris, A Memoir,” Reprinted from American Ophthalmological Society Transactions, 1903, (Hartford Press, The Case, Lockwood and Brainard Company, 1903), pp. 4, 5-6, Google Books, accessed 5/20/2020.

[24] Risley , ibid., p. 11.

[25] Risley, ibid., pp. 9-11.

[26] Carte de visit portrait of William Fisher Norris, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/104076740/william-fisher-norris, accessed 5/27/2020.

[27] Medical schools had long been using the Philadelphia Hospital (part of the Philadelphia Almshouse and eventually called Philadelphia General Hospital) for clinical teaching purposes. This hospital moved west of the Schuylkill in the 1830s from its previous location at 10th-11th St., between Spruce and Pine. See Lawrence C, History of the Philadelphia Almshouses, p. 42, and for a fuller discussion about the impact of the move on medical student education, see Chapter VIII.

[28] Photo of Medical Hall from the University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania, http://hdl.library.upenn.edu/1017/d/archives/20011001001; see also Penn Medicine News, “Changing Places: Penn Medicine’s Educational Homes,” 12/20/2014 https://www.pennmedicine.org/news/news-blog/2014/december/changing-places-penn-medicines, accessed 5/20/2020.

[29] Thorpe F, William Pepper, M.D., L.L.D. (1843-1898), Provost of the University of Pennsylvania (J.B. Lippincott Company, 1904), p. 44, Google Books, accessed 5/19/2020.

[30] Photo of University Hospital from the University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania, http://hdl.library.upenn.edu/1017/d/archives/20011001001 accessed 5/20/2020.

[31] LCP Share 781 had been previously held by George William Norris’s great-uncle Isaac (1801-1890), and his two great-aunts, Hannah Fox Norris (1804-1884) and Emily Norris (1816-1901). George William acquired the share in 1902.

[32] Hoeber P, History of the Pennsylvania Hospital Unit (Base Hospital No. 10, U.S.A.) in the Great War (Paul B. Hoeber, 1921), pp. 31-32, National Library of Medicine, Digital Collections, http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/14230590R, accessed 5/19/2020.

[33] Surgeon General’s Office, Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War, Vol. 1 (Government Printing Office, 1923), pp. 93-94, U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections, http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/14120390RX1 accessed 5/19/2020.

[34] Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, Digital Image Library, “A Philadelphia Physician Encounters the Great War,” https://www.cppdigitallibrary.org/exhibits/show/great-war-physician/item/1540, accessed 5/21/2020.

[35] Hoeber P, History of the Pennsylvania Hospital Unit (Base Hospital No. 10, U.S.A.) in the Great War, n.p.,photo facing p. 32.

[36] Pennsylvania: A Record of the University’s Men in the Great War Supplement to the Alumni Register, October 1920, p. 47. (no publication information), Google Books, accessed 5/19/2020.

[37] George W. Norris scrapbooks, 1875-1963, Ms. Coll. 1121, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania, Finding Aid, http://hdl.library.upenn.edu/1017/d/pacscl/UPENN_RBML_PUSpMsColl1121, accessed 5/21/2020.