Pandemic Panic: Mary Shelley’s The Last Man

Jim Green, Librarian

Pandemics often cause panic: contagious, widespread fear. Pandemic panic is partly caused by fear of death; but more often it is caused by a breakdown of the social order as a side effect of pandemic: anything from a toilet paper shortage (which is said to be caused by panic buying) to stock market plunges (panic selling).

For example, the cholera riots that broke out in Liverpool in 1832 were caused not so much by fear of the disease as by a breakdown in the public’s trust in the medical profession. This was understandable in that the doctors seemed to be helpless to stop the disease. But the immediate cause of the riots was a viral rumor that doctors were taking stricken patients to the hospital and killing them in order to use their bodies for dissection. The kernel of truth to the rumor was that a few years before, two Edinburgh men named Burke and Hare were convicted of murdering people in order to sell their bodies to the anatomy school. One of the calls of the Liverpool mob was “bring out the Burkers.”

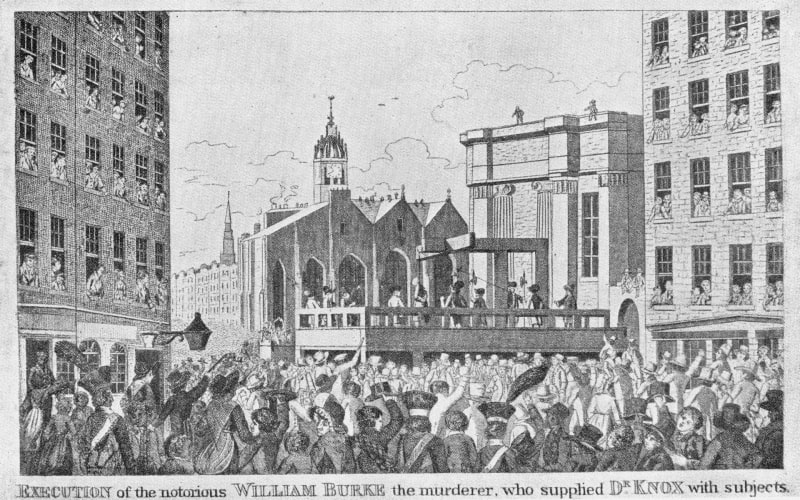

“Execution of the Notorious William Burke,” engraving, Edinburgh 1829. Gift of Charles Rosenberg, 2017.

In 1829 William Burke was convicted of murdering people and selling their bodies to physicians for dissection. He was hanged in Edinburgh before a crowd of 25,000. During the 1832 cholera outbreak in Liverpool, a rumor that something similar was happening there helped touch off a riot.

The opposite of pandemic panic was the wonderfully cool John Snow removing the handle from the Broad Street pump. Boccaccio, Defoe, Mather, Franklin, and Carey all kept their heads, at least in print. The literature of pandemic panic, on the other hand, was created by Gothic writers like Charles Brockden Brown and Edgar Allan Poe. Their panic was about a breakdown of the social order. The disease was a metaphor.

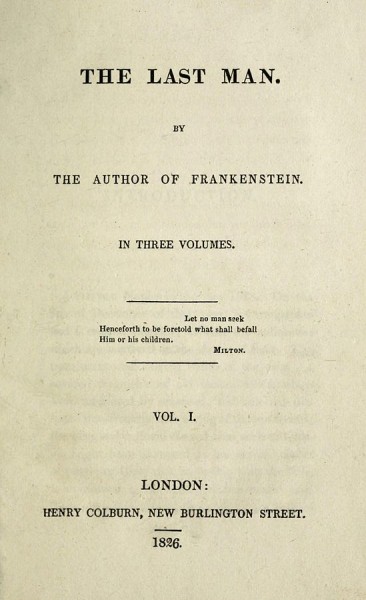

Mary Shelley’s novel The Last Man (1826) imagined the extermination of the entire human race by a plague that is pure metaphor. She does not even bother to describe its symptoms, saying in effect that if you want to know what plague is like, read Defoe. Set in the late 21st century, it is narrated by Lionel Verney (a stand-in for the author), a former radical who comes under the moderating influence of Adrian (representing Mary’s husband Percy), the son of the last king of England and a lover of civilization, scholarship, and philanthropy. Their friend Raymond is the benevolent Lord Protector and also a leader of the Greeks in their long war with the Turks. (He is obviously Byron.). They and their sisters and lovers are involved in intricate affairs with each other, not unlike those of the real-life Shelley circle.

Mary Shelley, The Last Man. London, 1826. Library Company of Philadelphia.

These affairs destabilize the government, leaving it unprepared for the plague heading their way from war-torn Turkey. The effect of plague is intensified by a series of natural disasters, including a black sun, earthquakes, and tidal surges that submerge half of England. Anarchy ensues, and seeking refuge, the characters head for the Mediterranean, where the sublime landscapes beloved of the romantic poets provide the backdrop as, one by one, they all die of various causes, along with their several children by each other. (This too is autobiographical. Mary lost three children in quick succession; then their father died in 1822, followed by Byron in 1824. Most of their lovers and their children died as well). In the last chapter, Verney swims ashore from a final shipwreck, realizes he is the last man, and vows to spend the rest of his life wandering the earth and writing the book we are reading.

Reginald Easton, Mary Shelley, 1857. Miniature, oil on ivory, an idealized portrait of her as a young woman. She wears a circlet of pansies for remembrance, as she does in Richard Rothwell’s life portrait of 1840.

The panic in The Last Man is not acted out by the characters. They are wrapped up in each other’s joys and sorrows and bravely soldiering on. The narrator is calm and optimistic, even after he realizes he is alone in the world. But the reader knows from page one that this will not end well, and we watch in horror as the doom approaches little by little over hundreds of pages. Lots of novels and plays end with the destruction of their major characters. The Last Man ends with nothing less than the destruction of the whole human race. The novel is one long panic attack.

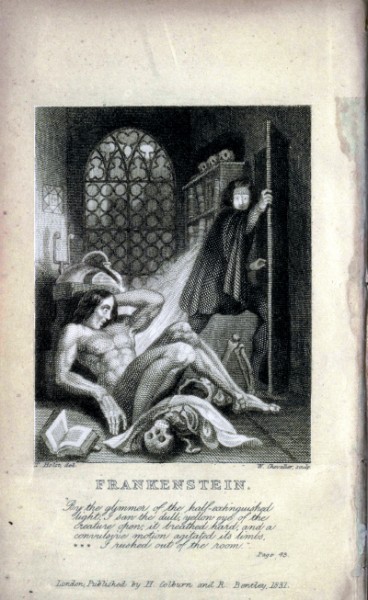

The Last Man is usually described as the first post-apocalyptic science fiction novel, and it is now far better known than it was in the author’s lifetime. The Library Company at some point acquired the first edition, which is now extremely rare. Mary Shelley’s far better-known Frankenstein is sometimes called the first science fiction novel, period. We did not get the first edition when it was published in 1818, but in 1849 we did manage to get a copy of the Bentley Standard Author edition, heavily revised by the author to make Frankenstein the scientist less of a megalomaniac, less of a radical. Sadly, that copy disappeared some time before 1900, the common fate of popular books in public libraries. Now we will probably never be able to afford any of its early editions. A copy of the first edition, inscribed to Lord Byron by the author, recently sold at auction for £350,000. A copy of the Bentley edition is now available for $19,500, and a copy of the first American edition (Carey, Lea and Blanchard, 1833) can be had for a mere $27,500. Would anyone like to buy one or two of them for us?

Frontispiece to the London, 1831 edition of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which she heavily revised for the Bentley Standard Author series. The Library Company once had an 1849 reissue of this edition.

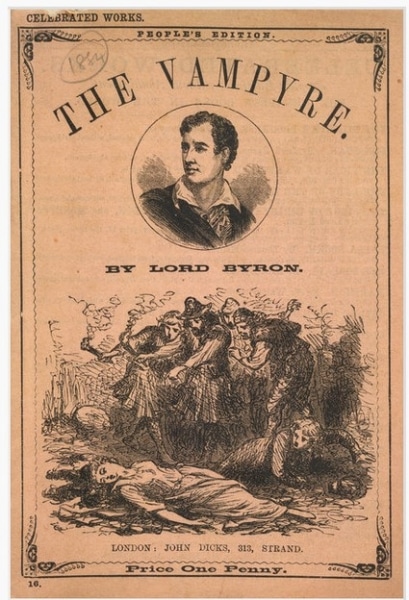

I won’t attempt to summarize Frankenstein, but anyone who has read it or seen a movie version knows it is a story where everyone gives way to blind panic, sooner or later. Also fairly well-known is the novel’s origin story: Byron, the Shelleys, and their friend Dr. John Polidori were staying in a villa on Lake Geneva in the summer of 1816, and, kept indoors by rainy weather, they decided to have a contest to see who could write the scariest story. Mary won with Frankenstein, but runner up was Polidori’s story The Vampyre. Another first for a literary genre, another story of blind panic—vampirism is another metaphorical contagion! (We have the first edition of 1819 and the first American edition, published in Philadelphia the same year by Moses Thomas. Thomas barely managed to bring it out, so devasted was his business by a financial crisis, known then and now as the Panic of 1819).

Front cover of John Polidori’s The Vampyre, People’s Edition, London, [1882]. Polidori’s story was written in 1816 while he was staying in Switzerland with Byron and the Shelleys. It was often attributed to the far more famous Byron.

What is less well-known about this moment in which so many genres of horror were born is that the rainy weather that kept these writers indoors was actually one of the worst climate disasters of modern times. In 1815 a volcano erupted on the Indonesian Mount Tambora, and an enormous dust cloud slowly drifted westward, causing what was known as the year without a summer. In northern Europe the sun never shone, freezing rain fell constantly, harvests failed, and 200,000 people starved to death. This was not a pandemic, of course, but it had many of the same effects. Crowds of starving people roamed the countryside crying out for food and dying by the roadside. Food riots broke out everywhere, but the violence was worst in Switzerland.

Map of the global spread of the ash cloud from the 1815 eruption of the Mt. Tambora volcano. From Kyra Cornelius Kramer, author and freelance medical anthropologist

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above a Sea of Fog, oil painting, ca. 1817.

This famous painting may represent weather conditions in Switzerland in 1816 during “the year without a summer.” It is sometimes used as cover art for Shelley’s The Last Man, which recalls her experience of that environmental catastrophe.

Were the writers in the lakeside villa oblivious to this total environmental and social collapse? Probably not, though none of them commented on it directly in their writing. It has been suggested, however, that the lurching, ragged, desperate monster Shelley imagined was based on the real half-dead people she must have seen all around her that summer. And it seems to me that in The Last Man, Shelley returned in her imagination to the summer of 1816, to the same cast of characters, to the real apocalypse that was happening all around them, and to the loss of almost everyone she loved.