Pandemic Reading: Cholera: John Snow‘s Map and Poe’s “Red Death”

Jim Green, Librarian

Hardly had the threat of yellow fever begun to recede in the northern part of the U.S. when a new plague emerged that was in some ways even worse: Cholera. Its main symptom was a sudden onset of painful, profuse, watery diarrhea, which resulted in dehydration so severe that the victim could die in a few hours. The sheer terror cholera inspired could mimic its symptoms. It was a truly diabolical disease.

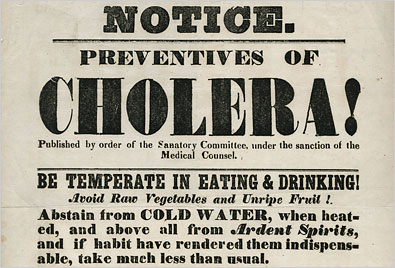

Cholera had long been endemic in parts of India, but an outbreak in 1817 spread to China and Indonesia, making it the first cholera pandemic. Millions died. The second pandemic also began in India in 1829 and spread north to Russia and from there across Europe to London and Paris, reaching the U.S. in 1832. This poster issued by the New York Board of Health in 1832 shows how the disease was believed to be caused by intemperance. It was also commonly blamed on foul air from cesspools and poor ventilation in slum houses.

We have a copy of this poster, the gift of Charles Rosenberg,

whose first book, The Cholera Years (1962) was a pioneering

work in the social history of medicine. In 2017 he

donated over 200 books on Cholera to the Library Company.

In New York 3,500 people died of cholera that year, but in Philadelphia the death rate was one-quarter of New York’s. This was attributed to Philadelphia’s superior water works, which provided plenty of fresh, clean water to cleanse the streets of filth.

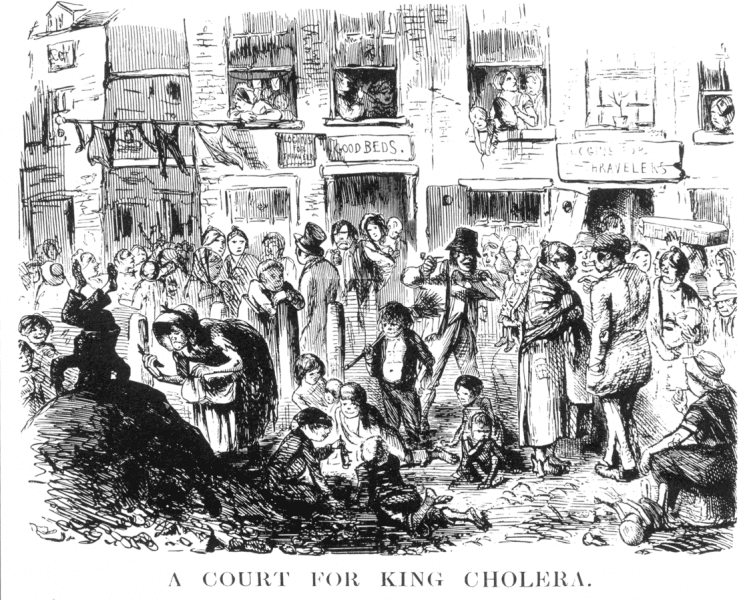

The connection between cholera and water supply was starting to be made, but the old idea that it was transmitted by foul air and filth was still prevalent. When cholera returned to London in 1852, the magazine Punch ran a cartoon depicting a London slum as “A Court for King Cholera.”

Punch, 1852. Gift of William H. Helfand.

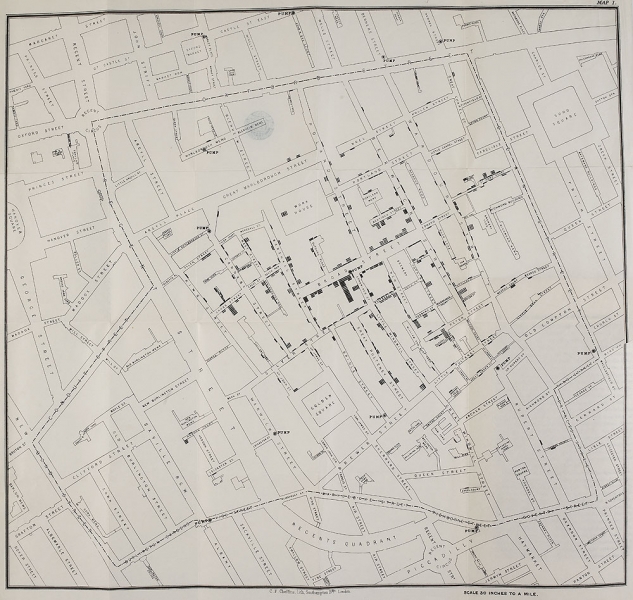

It was during that London outbreak that Dr. John Snow began to test a theory that cholera was transmitted not by air but by polluted water. In 1854, while questioning the inhabitants of a cholera hot spot in Soho, he noticed that many victims got their water from the pump in Broad Street. (The Court of King Cholera must have looked much like Broad Street.) Some people went out of their way to drink from the pump because they thought the water tasted better. Even within the same family, those who drank from that pump got sick and those who used other pumps did not. He mapped these Soho cases and found that the pump was at the center and that the rate of infection correlated with the distance from it. Using this map, he convinced the local council to remove the handle from the pump, and the outbreak ceased. The first publication of this map, a pioneering work of data visualization, is in the cholera collection donated to the Library Company by Charles Rosenberg in 2017.

In Snow, John. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 2nd Ed, London, 1855. Gift of Charles Rosenberg.

It was many years before the bacteria that caused cholera was identified, but Snow’s discovery of its mode of transmission is now seen as the founding event of the modern science of epidemiology.

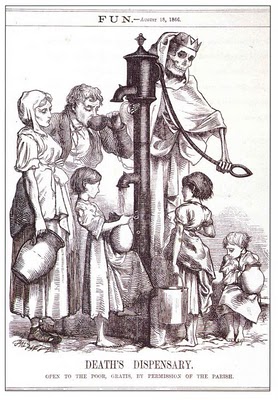

Snow’s theory was at first controversial, but during the next outbreak in 1866, another pioneering epidemiologist named William Farr identified contamination in a new sewer system still under construction as the source of the cholera. This 1866 cartoon in the British humor magazine Fun signals the popular acceptance of Snow’s theory.

Fun, 1866, Gift of William H. Helfand.

These great cartoons remind us that the 19th century saw an explosion of graphic images representing just about every aspect of life, and cholera is no exception. Looking at the graphics in our collection published during the cholera years, I’m struck by how many images of the Medieval Dance of Death were published. Its earliest known depiction was in a now-lost mural in a Paris cemetery dated 1424, but it probably arose earlier during the Black Death as an expression of piety or mass hysteria. Its many 19th century revivals, however, may have been sparked by cholera. Dr. James Rush, the melancholy son of Benjamin, owned three examples published in the 1840s, including two reproducing Holbein’s woodcuts from the 16th century. School book publisher Charles G. Sower, a descendant of the first German American printer, had five, and another seven came from various other sources, including direct purchase for the circulating collections. Here is one of the 34 images from the Holbein series: The Abbess, being dragged by Death from her nunnery, looking far from ready to meet her maker:

How about the great cholera novel? I haven’t found a 19th century counterpart to Love in the Time of Cholera, but the great cholera short story is Edgar Allan Poe’s “Mask of the Red Death” which was first published in Philadelphia in the May 1842 issue of Graham’s Magazine. It takes place during a plague he calls the Red Death, and except for blood taking the place of watery diarrhea, it sounds la lot like cholera: “No pestilence had ever been so fatal, or so hideous. Blood was its Avatar and its seal – the madness and the horror of blood. There were sharp pains, and sudden dizziness, and then profuse bleeding at the pores, with dissolution… And the whole seizure, progress, and termination of the disease were the incidents of half an hour.”

The hero of the story, Prince Prospero, decides to evade the plague by self-quarantining himself and a thousand of his courtiers in an impregnable and well-provisioned castle. After a few months, he stages a masked ball, which around midnight degenerates into a frenzied dance of death. A masked stranger appears, who excites disgust and fear with his inappropriate costume. “The figure was tall and gaunt, and shrouded from head to foot in the habiliments of the grave. The mask which concealed the visage was made to resemble the countenance of a stiffened corpse… the mummer had gone so far as to assume the type of the Red Death. His vesture was dabbed in blood – and his broad brow, with all the features of the face, was besprinkled with the scarlet horror.” When the crowd unmasks him, “they gasp in unutterable horror at finding grave-cerements and corpse-like mask which they handled with so violent a rudeness, untenanted by any tangible form. And now was acknowledged the presence of the Red Death. He had come like a thief in the night. And one by one dropped the revellers in the blood-bedewed halls of their revel, and died each in the despairing posture of his fall. And the life of the ebony clock went out with that of the last of the gay. And the flames of the tripod expired. And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.”

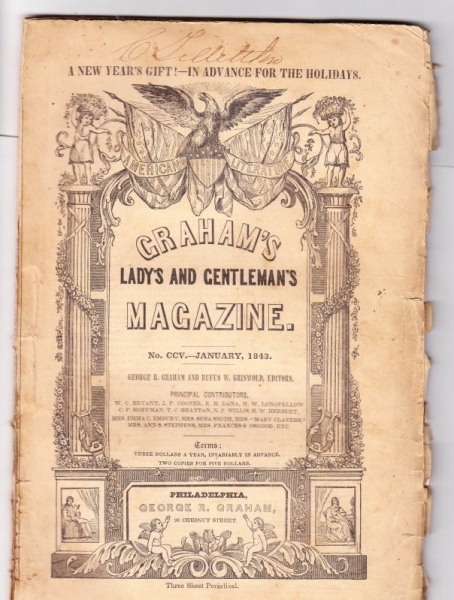

Here’s what the magazine cover looked like at the time:

If you want to read the story as it first appeared, mixed in with colorful fashion plates, scenic views, and portraits of lovely ladies, follow this link to page 257 of the May 1842 issue.