Pandemic Reading: Quarantine and Isolation at the Lazaretto

Jim Green, Librarian

Quarantine has its origin in the 14th century. During the Black Death, ships arriving in Venice from the east were required to sit at anchor before landing for forty days: quaranta giorni. The idea of isolating the sick is much older, of course. Victims of leprosy in ancient Greece and India were deemed unclean and often isolated. For early Christians the beggar Lazarus was the patron saint of lepers, and hospices for them (and later for plague victims) were called Lazarettos.

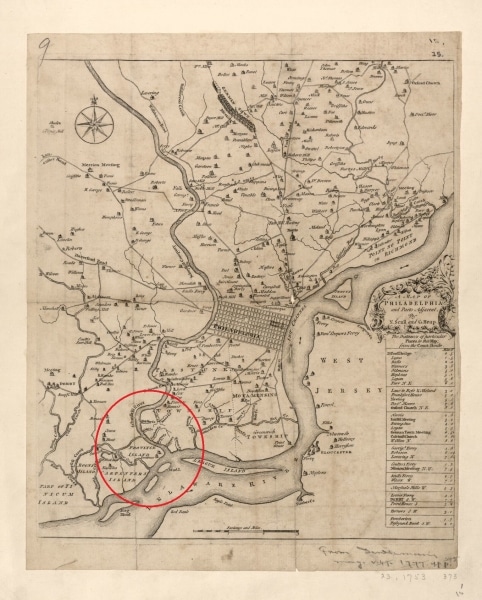

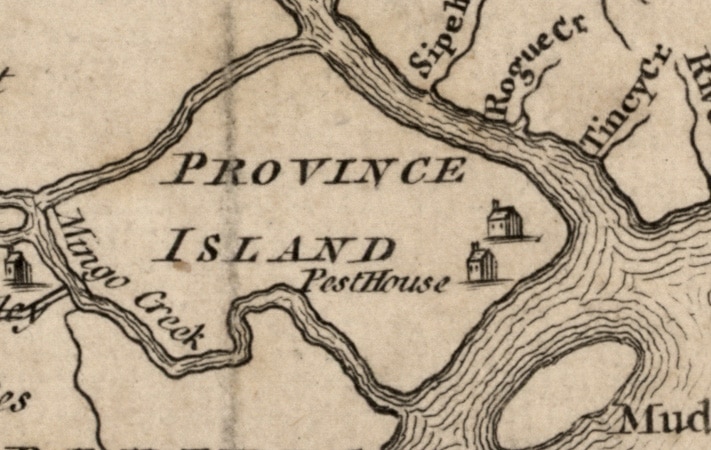

In the U.S., quarantine began in response to yellow fever. In 1742, after an outbreak the year before, a quarantine station was opened on Province Island where the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers meet. The 1753 Scull and Heap map shows a “pest house” there. It was sometimes called the Lazaretto. In 1799, after three successive annual outbreaks of fever (that’s not counting the 1793 calamity), the city created a board of health, which built a much larger Lazaretto a few miles farther downstream at Essington, a few hundred yards from what is now the west end of the airport runway.

Nicholas Scull and George Heap, A map of Philadelphia and parts adjacent, From Gentleman’s Magazine, vol. 23, London, 1753 p. 373. (Full image left, detail of Province Island showing pest house right.)

That building still stands. It was saved from demolition for an airport parking lot and has been recently been restored. To see what it looks like, and for the story of its preservation, see Inga Saffron’s Inquirer article.

From 1801 to 1893, every ship entering the port during warm weather months had to stop at the Lazaretto. If there were any sick passengers or crew, they were removed to the spacious 200-bed hospital. The healthy had to remain on board, sometimes for days or even weeks, to make sure they were not infected. The ten-acre site was well-fenced and gated to exclude visitors and prevent escapes.

Travelers and immigrants thought quarantine was a nuisance, but their complaints were minor compared to those of the mercantile class, who decried it as anti-business and denied the science on which it was based. Nevertheless, it seems to have worked. After 1822, yellow fever was again confined to more southern ports. As the years passed, occasional outbreaks of yellow fever were safely contained, and the hospital was kept busy by other diseases such as typhus. Lazaretto records suggest that over 80% of the sick recovered. That is even more amazing considering that there were no hallways in the hospital; each room opened directly onto the next, which must have made isolation very difficult.

The best account of the Lazaretto I’ve found online is an interview with Penn medical historian David Barnes by former Philadelphians Geoff Manaugh and Nicola Twilley. It’s on Manaugh’s marvelous BLDGBLOG.

What the world is going through now involves both quarantine of the sick and isolation of the presumed healthy. Some people compare this isolation to house arrest. The great classic of house arrest is Count Xavier de Maistre’s witty Voyage autour de ma Chambre, first published in 1794. The Count (1763-1852) was confined to his 700-square-foot room for six weeks for dueling, and to pass the time he wittily imagined himself as a traveler exploring a strange land. It was partly a parody of a travel book, and partly an imitation of the style of Laurence Sterne’s hugely popular Sentimental Journey, through France and Italy (1768), a quote from which appears on the title page. It was first published in English in Philadelphia by Carey, Lea and Carey as A Journey Round my Room (1829). Here is an excerpt:

While travelling within my chamber, I seldom go in a straight line, but from my writing table I repair to a picture which stands in one corner; I advance obliquely towards the door; and although at the beginning, my intention be to reach that end, if I meet on my way with a chair, I make no compliments but throw myself into its arms.What a convenient piece of furniture is an arm-chair! It is indeed indispensable to a meditative mind…. Beyond my arm-chair, going north you will find my bed, which stands in the back part of my chamber, and which offers the most pleasant prospect. Etc.

Thanks to Google, I was able to work out that the translator was Jules de Wallenstein, secretary to the Russian embassy in Washington. This explains how the book was first translated in the U.S. rather than England. De Wallenstein translated other works by de Maistre and was a frequent contributor to American learned journals such as the American Philosophical Society Transactions. John Quincy Adams thought he was “the most amiable and intelligent member of the Diplomatic Corps that I have ever known in the United States” (Diary 24 August 1829). If we ever owned this Carey edition, it is long gone, replaced by a New York, 1871 edition by a British translator, who in his preface claimed to be the first. In addition, our cosmopolitan shareholder Anne Hampton Brewster owned a copy of de Maistre’s Oeuvres Complètes (Paris, ca. 1851) including his Voyage.

An illustration from Xavier de Maistre, A Journey round my room (New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1871).

You can read Journey Round my Chamber in a sitting, unless like the author you want to make a little go a long way, in which case you may savor a chapter or two a day.