Pandemic Reading: Bubonic Plague and Boccaccio’s Decameron

Jim Green, Librarian

This is the first of a series of blog posts about books in the Library Company’s collections about contagion and confinement, epidemics and quarantines.

I’ll begin with another series, the tales supposedly told to each other by a group of ten young people who fled to a villa in the hills above Florence at the height of the bubonic plague in 1348. Their aim was to break the monotony of their isolation and to take their minds off the horror of the plague in the city below. Such is the frame into which Giovanni Boccaccio set the hundred tales in his Decameron, one of the earliest masterpieces of European vernacular fiction. (In Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, Erich Auerbach offers a brilliant close reading of one of the tales and concludes, “of such artistry there is no trace in earlier narrative literature.”)

Raffaello Sanzio Morghen. Giovanni Boccaccio. Reproduction of a Dutch engraving, 1822

Like the tellers of these tales, I am isolated, with no access to bookstores or libraries, so I had to hunt down my yellowing ‘60s-era college textbook copy to refresh my memory. Its back cover says these stories “tell of skulduggery [sic] and rascality, of thievery, murder, and banditry, of cuckold husbands and faithless wives. Written in a cynical age, against a background of impending doom, these lusty tales are unfolded without restraint or false modesty.” The clunky 1930s translation makes this edition even more of a period piece. Nevertheless, I am once again enjoying these tales hugely.

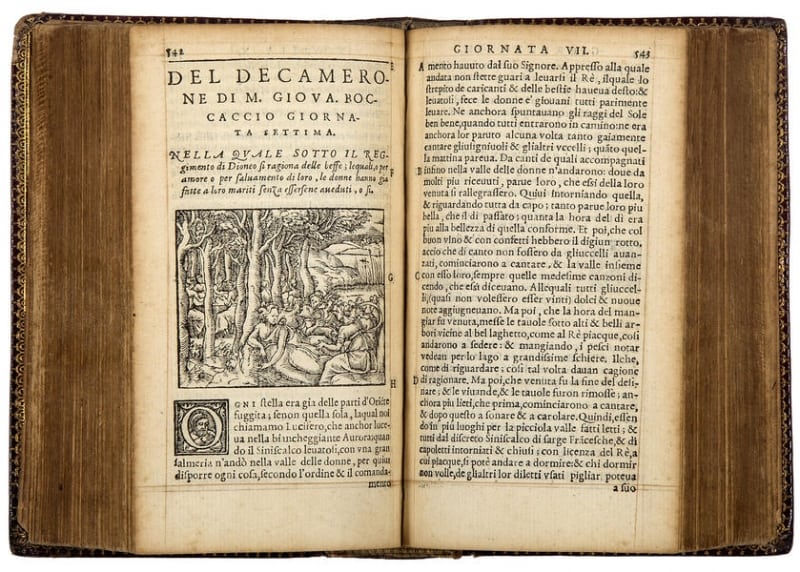

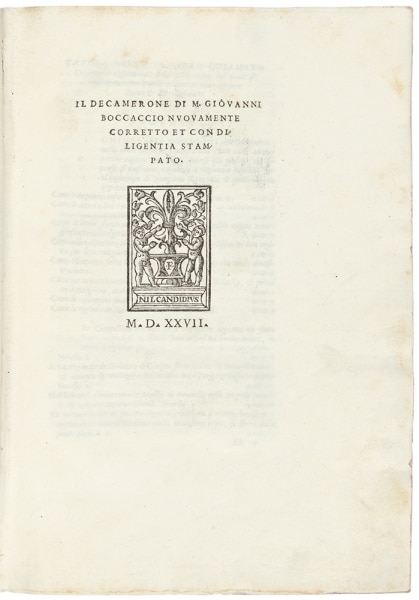

The Library Company’s earliest readers did not have that pleasure, unless they were linguists, like James Logan, who had a 1555 Lyon edition of the Italian original. (He also had other works by Boccaccio in a 1494 Venice edition, the second oldest book he owned). In the 1790s we got a 1702 edition in French. Anne Hampton Brewster, Philadelphia journalist and novelist living in Rome in the mid-19th century, had what appeared to be the famous Giunta edition, printed in Florence in 1527, which she donated to the Library Company. (It is actually an 18th century type facsimile; whether or not she knew that, it is a testimonial of her good taste).

Giovanni Boccaccio, Il Decamerone, (Lyon: G. Rouille, 1555). James Logan owned a copy of this lovely illustrated editon of the Decameron in the 1740s. Courtesy of Libreria Antiquaria Alberto Govi, Modena, Italy.

Giovanni Boccaccio. Il Decamerone. (Florence, Giunta, 1527; i.e., Venice, Etienne Orlandini, 1729). Anne Hampton Brewster owned a copy of this fine facsimile of a renowned 1527 edition. Courtesy of Donald Heald Rare Books, New York.

There were several English translations available, going back to 1620, but we had none of them. Benjamin Rush’s son Richard got an 1820 English translation while he was ambassador to the Court of St. James, but it didn’t come to us until much later. His brother James got another edition in English while he was abroad in 1835, which reached us after his death in 1869. We did not acquire an edition in English until 1855, and that was published in London.

We just last year acquired what may be the first American edition, published by one Calvin Blanchard in New York in 1851. It is quite rare, and it has an odd feel, as if it was printed by an amateur; plus it is illustrated with steel engravings in a peculiar style that attempts but fails to be salacious. It turns out that Blanchard was a specialist in erotica, both classical and very modern. The first respectable American edition did not appear until 1878, over the imprint of the Philadelphia art book publisher George Gebbie. We got that when it came out, but we accessioned it into the Loganian library, where its circulation was somewhat restricted. Perhaps Boccaccio was just too “lusty” for American tastes. Perhaps our readers preferred their tales told with a bit of restraint and true modesty.