Working with Graphics is Not Just Fun

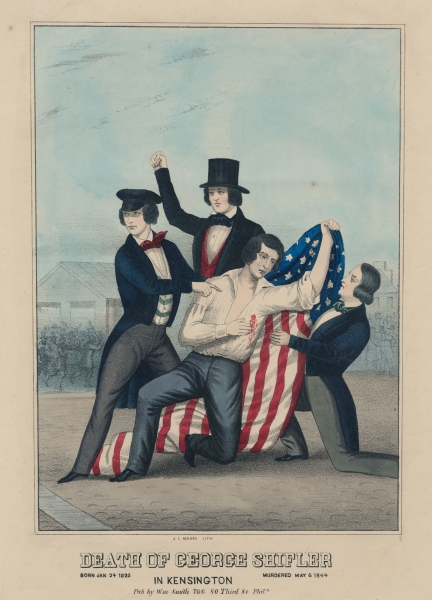

John L. Magee, Death of George Shifler in Kensington. Born Jan 24 1825. Murdered May 6 1844 (Philadelphia: William Smith, after 1850). Hand-colored lithograph.

I must admit I always bristle a little when patrons visit the Graphic Arts Department and enthusiastically state how much fun our job must be because we work with pictures. I know the patron often says these words without any disrespect. However, for the graphics scholar in me, the underlying sentiment of their statement translates to visual works are of lesser research value than written ones. Reading an image does engage an individual in a different way than reading words. And reading a book, like reading pictures, can be fun. But reading pictures is also serious work. As noted by scholars of reading, before you can learn to read, you need to learn to look. Pictures were our first means of reading. This does not demean this manner of literacy. It demonstrates its importance.

Art historian Sarah Lewis has advocated that to be an engaged citizen, one must also be visually literate. In today’s society and in an era where digital technology is making it ever more possible to seamlessly see what should not be believed, visual literacy is a safeguard to understand what we see today and a tool to understand what was seen by those in the past.

Multitudes of materials in the Graphic Arts Department speak to the pivotal role of images in our nation’s and Philadelphia’s complex history. Close looking of the undated sociopolitically-charged print Death of George Shifler in Kensington. Born Jan 24 1825. Murdered May 6 1844 by lithographer John L. Magee (b. ca. 1820) is a case in point. Published in Philadelphia by William Smith, it has been widely used by contemporary scholars to illustrate the Nativist Riots that occurred in the city in the spring and summer of 1844. The sensational scene depicts the death of eighteen-year old Nativist George Schiffler (1825-1844) during the May 1844 rally of the anti-immigration organization in the Irish-Catholic neighborhood of Kensington.

Given the dramatic design reminiscent of heroic art paintings, and the title, it is not a surprise Shifler has been purported as a partisan print issued about 1844 and reflecting the pro-Nativist ideology of its creators. Further research, however, has raised some questions about these assumptions concerning the date of the print, as well as the motive for its publication.

Magee as the artist raises the first red flag about the accuracy of the presumed circa 1844 date. He did not settle in Philadelphia from New York until 1852. Magee may have delineated the design while in New York for Philadelphia publisher William Smith, but Smith as the publisher also causes doubts about the supplied year of publication. Smith’s 706 South Third Street address in the imprint is his renumbered address after the 1854 consolidation of Philadelphia with its bordering townships. According to city directories, his establishment remained on the same block of South Third Street during the 1850s. Consequently, Smith’s pre-1854 lithographs should contain his pre-consolidation address of 264 South Third Street. The possibility that Shifler was a reissue was considered, but not until recently was another version of the print located. Within the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History is an earlier version of Shifler.

Also titled Death of George Shifler in Kensington. Born Jan 24 1825. Murdered May 6 1844, the unsigned lithograph is further captioned “Respectfully dedicated to the Native Americans by Shifler No. 1 Southwark Phila.” Additionally it contains a traceable imprint “Sold by Pierson No. 349 So. 2nd Phila. R. DeWitt, Tribune Buildings, N. York.” Knowing the Nativist Shifler Association No. 1 commissioned the print is useful. However, the names of the distributors Pierson and DeWitt facilitate even more concrete evidence to deduce it is an earlier-issued lithograph than the Smith. Pierson was Southwark (and Nativist supportive) bookseller Hiram B. Pierson (b. ca. 1814). DeWitt was New York publisher Robert DeWitt. Each concurrently operated from their cited business address between circa 1850 and circa 1853. Eureka! There was an earlier, circa 1850 print after which Magee and Smith designed their post-1854 lithograph. But questions still remain, including why would Smith publish a version of the lithograph over a decade after the sensational, Nativist event portrayed?

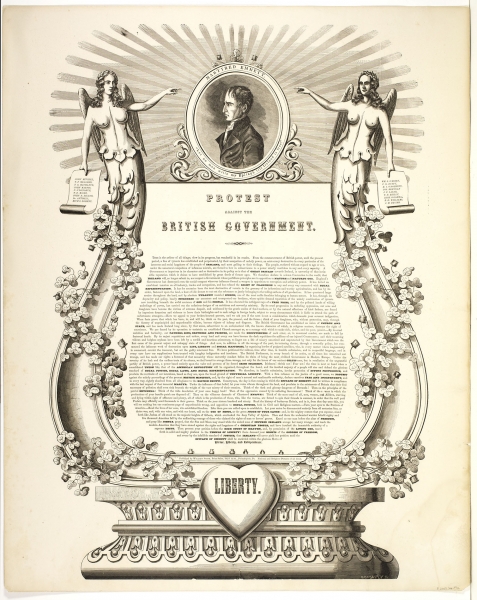

Joseph H. Brightly, Protest Against the British Government (Philadelphia: William Smith, ca. 1858). Lithograph.

Other evocative works published by Smith held at the Library Company further confound his possible partisan incentive to publish Shifler. Smith also printed for a niche, Irish-American market. The circa 1858 print Protest Against the British Government containing a portrait of Irish martyr Robert Emmett especially lends credence to this observation. The motives for the production of the later Shifler lithograph prove as complicated as those that incited the event it portrays. A profitable print exploiting a sensational event in the history of the city may have been the primary impetus for its reissue by Magee and Smith — a motive more important than religious and political allegiance as many have alluded was the impetus for its production. It is visual history that is perfectly imperfect.

Erika Piola

Curator of Graphic Arts and Director of the Visual Culture Program

Imperfect History is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation.