“Myself and the World”: Women Empowered by the Bicycle

This summer, Franklin & Marshall intern Lydia Shaw has been working on women’s history projects at the Library Company. In preparation for Women’s Equality Day (August 26, 2020), Lydia read Frances Willard’s 1895 book on her personal experience learning to ride the bicycle. Willard became enthralled with bicycling at a time when bicycling was a new pastime, and one associated with male athleticism. Lydia writes:

In the second half of the 19th century, a new, healthy, and excitingly challenging means of transportation appeared in American popular culture: the bicycle. The first bicycle (known as the “Ordinary”), the amusing-looking 19th-century bicycle of collective popular memory, had a giant front wheel and a small back wheel and was exclusive to young men who possessed the funds to purchase it. These same young men made yet more exclusive biking clubs, to which they could bring their female romantic partners as guests. It was in this capacity that women were included in the elite world of bicycling. Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, women were discouraged from riding a bicycle whatsoever. As Sarah Hallenbeck writes in Claiming the Bicycle: Women, Rhetoric, and Technology in Nineteenth-century America (2016), the bicycle was a masculine invention known for the athleticism and the competitive challenges it produced due to its “difficulty and danger” (5). Only once the tricycle emerged in the mid-1880s were women able to claim a bicycle as their own, albeit one with many adjustments from the Ordinary that kept women in a less athletic, gendered sphere. While riding the tricycle, which was easy and could not go as fast as Ordinaries and was thus “a ‘women’s machine’ to complement their own ‘men’s machine,’” women were defined in their relationship to male bicyclers (Hallenbeck 11). In this way, women and men could ride together, but women were still restricted to a lesser, more feminine role.

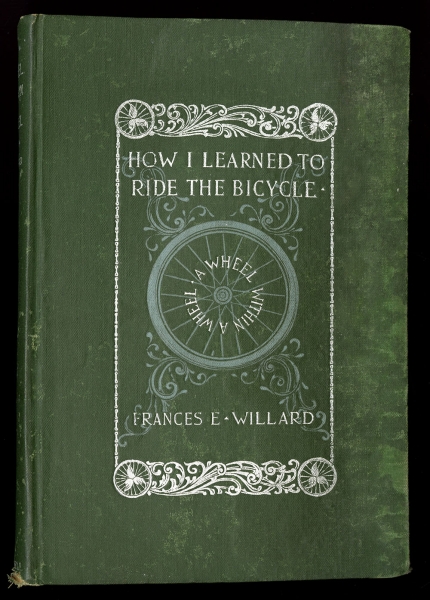

Frances Willard. Wheel within a Wheel (1895). Purchased with the Davida T. Deutsch Women’s History Fund.

Women came into the male-dominated sphere of athletic bicycling after the Safety bicycle was invented in the late 1880s, a bicycle that gave its user speed while maintaining a certain level of comfort in relation to the more precarious Ordinary bicycle. Here was a bicycle upon which women could level the playing field and compete with men, thus disrupting the gendered spheres of bicycling in which women were limited to tricycles due to their “inferior anatomy.” The models of the Safety bicycle still differed between genders, however, as Hallenbeck writes, “as bicycle makers large and small continued to offer machines that materialized small differences between the sexes, even as they allowed for greater companionship between male and female riders” (25).

One way that women asserted their role in the world of bicycling was through authoring fictive and instructive literature, which made bicycling more welcoming to young women. While most stories that featured women bicyclers positioned them in relation to their male bicycler beaus, Hallenbeck observes that “[w]omen writers of popular fiction complicated this narrative in productive ways, not radicalizing the characters but using their courtship entanglements as a means of establishing, in their heroines, an ethos that blurred the lines between appropriate feminine and masculine traits” (79). The female characters written by women themselves had thoughts and ambitions of their own, and they enjoyed riding the bicycle for reasons other than engaging with men. Women found the thrills and independence of bicycling not discouraged, but encouraged in these writings.

Frances Willard’s A Wheel within a Wheel: How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle, with Some Reflections by the Way (1895) is one of these texts. A Wheel within a Wheel is an autobiographical work in which Willard instructs women on how to use the bicycle, compares the learning experience of riding a bicycle to the greater themes of life itself, and provides political angles on why women should be allowed to ride a bicycle. Willard (1839-1898), who is best known for her work as the president of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, writes through the lens of a temperance reformer who advocates women’s agency with the bicycle in response to the 19th-century “woman question.” In fact, Willard writes, “[…] as a temperance reformer I always felt a strong attraction toward the bicycle, because it is the vehicle of so much harmless pleasure, and because the skill required in handling it obliges those who mount to keep clear heads and steady hands. Nor could I see a reason in the world why a woman should not ride the silent steed so swift and blithesome” (72-73). At fifty-three years of age, Willard concedes that when she began to learn to ride the bicycle, she struggled, but that it was the challenges she faced that made the process so meaningful and rewarding.

At the beginning of her book, Willard writes that since a young age she had been “an active and diligent worker in the world” who wholeheartedly loved the outdoors (8). Through bicycling, she asserts the power and agency of women, writing that women could benefit from learning “individual thought” from riding a bicycle (Willard 18). She also writes tips for her female readers, such as the importance of learning the mechanics of a bicycle for oneself, or to ride slowly before trying to “fly high” (Willard 21). Willard instructs women to present themselves well on a bicycle: “Let me remark to any young woman who reads this page that for her to tumble off her bike is inexcusable” (62). Perhaps hoping to bring a confident, capable image of a young woman on her bicycle instead of the supposed “weaker” gender who needed assistance with the machine she did not understand, Willard emphasizes that women can take hold of agency specifically as a woman on a bicycle.

Through writing A Wheel within a Wheel, Willard voices her opinions on “the woman question” of great concern when women organized and demanded reform in the second half of the 19th century. Knowing that her audience would comprise mostly women, Willard addresses her female readers directly. For example, when describing the benefits of bicycling, Willard writes, “He who succeeds, or, to be more exact in handing over my experience, she who succeeds in gaining the mastery of [bicycling], will gain the mastery of life, and by exactly the same methods and characteristics” (28). Willard chooses to posit “she” as the default pronoun when referring to bicyclists, knowing that representation of women in the sport would normalize their acceptance. Willard also suggests normalizing women bicyclists because “[t]he old fables, myths, and follies associated with the idea of woman’s incompetence […] are passing into contempt in presence of the nimbleness, agility, and skill of ‘that boy’s sister’; indeed, we felt that if she continued to improve after the fashion of the last decade her physical achievements will be such that it will become the pride of many a ruddy youth to be known as ‘that girl’s brother’” (40-41). Willard writes that many women are not just defined in relation to men. By centering women as skilled bicyclists in their own right, Willard asserts that women are just as capable as men in performing in spheres they had been previously excluded from.

Hallenbeck mentions Willard and A Wheel within a Wheel while discussing women’s authorial agency in the industry of travel writing. She asserts that “Willard constitutes in A Wheel within a Wheel a public of women bicyclists of varying ages and ability levels, all riding together and supporting one another both for their own self-improvement and for the betterment of women in general” (Hallenbeck 116). Hallenbeck’s statement rings true: throughout her book, Willard insists that women learn to ride the bicycle, implicitly suggesting that a mass public of women riding bicycles would help them secure greater freedoms both as individuals and as a collective. To express the independence and opportunities that women who bike will encounter, Willard writes, “I began to feel that myself plus the bicycle equaled myself plus the world” (27). In the conclusion to A Wheel within a Wheel, she leaves her female readers with a command: “Moral: Go thou and do likewise!” (Willard 75). For Willard, learning to ride a bicycle became a metaphor for women making their own way and taking power in a world previously defined by men.

Lydia Shaw, Franklin & Marshall Class of 2022

Works Cited

Hallenbeck, Sarah. Claiming the Bicycle : Women, Rhetoric, and Technology in Nineteenth-Century America. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2016.

Willard, Frances. A Wheel within a Wheel: How I learned to Ride a Bicycle, with Some Reflections by the Way. New York: F. H. Revell Co., 1895. https://archive.org/details/wheelwithinwheel00williala/page/8/mode/2up.