Philadelphia’s Earliest Museums, 1774-1827: Reconstructing a City’s Visual Culture

John C. Van Horne, Director Emeritus

Where in the 1780s could Philadelphians go to see a petrified shark’s tooth, silver ore from Iberia, an Indian belt of blue glass wampum, stuffed pumas, an albatross from the Cape of Good Hope, a mongoose from China, a feather war cap and cloak from Tahiti, and dozens of portraits of distinguished characters from the recently-won Revolution? The answer is the museums recently opened by two energetic entrepreneurs – the Swiss-born Pierre Eugène Du Simitière and the Maryland-born Charles Willson Peale. And there was much more besides in these two wide-ranging collections: paintings, prints, drawings, sculpture, other works of art, natural history specimens (both fauna and flora), ethnographic artifacts, antiquities, curiosities and lusus naturae, fossils, minerals, coins, books, pamphlets, and maps.

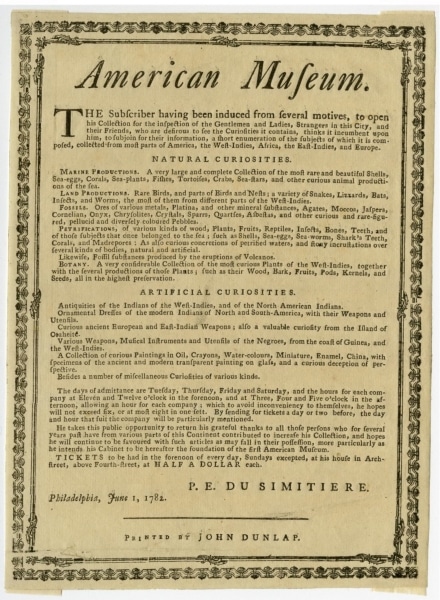

Now well underway is a digital humanities project to virtually reconstruct two of America’s earliest museums. The eccentric Swiss collector Pierre Eugène Du Simitière (1737-1784) opened his collection to the public on Arch Street in 1782; his short-lived enterprise ended with his death two years later. And just two years after that event, in 1786, artist Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) opened his own museum, which lasted into the mid-19th century and spawned offshoots in other American cities. Much has been written about these two museums (especially the much better-known Peale Museum), but nowhere is there a comprehensive accounting of just what these two museums held and exhibited to the public.

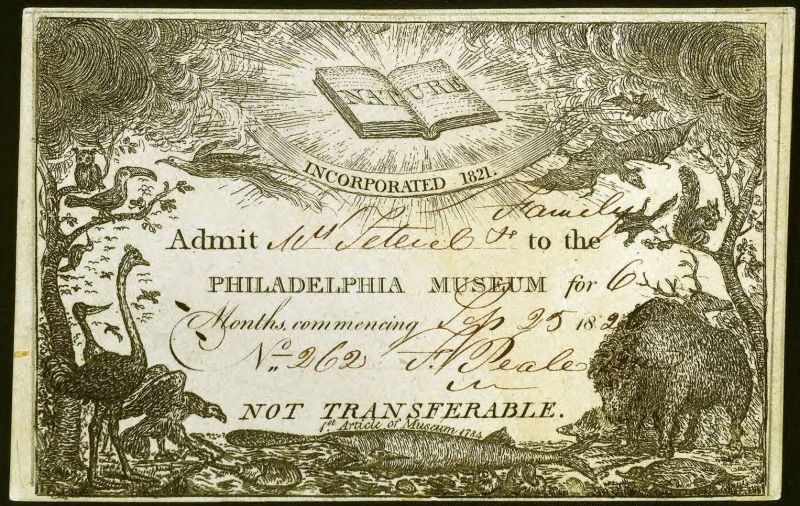

Admission Ticket to Peale’s Museum, American Philosophical Society, Mss.B.P31 — Peale-Sellers Family Collection

With my collaborator, Carol Eaton Soltis, a curator and noted Peale expert at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Trustee Emerita of the Library Company, I am creating a database (and ultimately a searchable, sortable website) of all the contents of the two museums that can be identified from numerous contemporaneous sources. Carol and I have enlisted Robert M. Peck (Senior Fellow of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University and another former Library Company Trustee) as our natural history advisor. The website will provide scholars and the interested public with access to the rich cultural world of Philadelphia during the half-century from the year Du Simitière settled in Philadelphia and began showing his collection in 1774 until Peale’s death in 1827. It is being developed by the Center for Digital Editing at the University of Virginia (whose talented staff built my previous website) and will be hosted by the American Philosophical Society, of which both museum founders were members and curators.

I first became interested in Du Simitière almost the day I arrived at the Library Company as Librarian (as the director was then known) in January 1985. I was immediately informed that the year was the 200th anniversary of our having acquired, at auction, much of the printed and manuscript materials that had made up his collection – more than 200 books; almost 800 pamphlets; hundreds of newspaper issues; scores of broadsides, many of them unique examples from the era of the Revolution; and numerous prints and drawings. Staff members Gordon Marshall and Mary Anne Hines had already begun to work on an exhibition of the highlights of that acquisition, which opened six months later. Ever since then I have wondered about the extent of that Museum. The broadside announcing the auction sale of its contents after Du Simitière’s death was tantalizingly vague as to the contents; it listed books individually by title but then aggregated other materials under such heads as “coins,” “preservations in spirits,” “fossils and petrifactions,” “drawings and prints,” “Indian and African antiquities, dresses, weapons, utensils, etc.,” and “an elegant collection of shells and other marine productions.”

Charles Willson Peale and Titian Ramsay Peale, View of Peale’s Museum in the Long Room, Second Floor of the State House (Independence Hall), 1822, Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase, Director’s Discretionary Fund

Fortunately, there are contemporaneous sources that enable us to compile a more detailed list of the contents, because Du Simitière kept thorough lists of his acquisitions that are now among his papers at the Library of Congress. And in 2017 our shareholder David Doret discovered and donated to the Library Company the manuscript inventory of Du Simitière’s estate, which sheds further light on his holdings. Despite the fact that we have had hundreds of Du Simitière’s books, pamphlets, broadsides, and newspapers in our collection for 235 years, it is only now, as part of this project, that a notation of his ownership is being added to our WolfPAC online collection catalog – thanks to the efforts of Chief of Reference Connie King. Being able to search the catalog for Du Simitière in the provenance field will enable us to easily extract those records and add them to our museum database and website.

Broadside Announcing the Opening of Du Simitière’s American Museum (Philadelphia, 1782), Library Company of Philadelphia

There are also numerous contemporaneous sources that enable us to itemize several thousand items in the Peale Museum — a manuscript Accessions Book that begins in 1804 at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania; dozens of newspaper announcements of recent donations; several manuscript and printed guides and other publications of the Museum; and Peale’s own autobiography and extensive correspondence, most of which is at the American Philosophical Society.

All these sources will be mined to populate the database and website. Each entry will record all pertinent information (description from the contemporaneous source, date of acquisition, name of donor, common and scientific name of natural history specimens, and description of works of art). Each entry has been assigned two classifications (type of object and geographic origin) to facilitate searching. One important “field” in this database will be the present location of anything known or discovered to have survived. The website will also include digital images of items that have survived and images of surrogates in the many instances when the actual items have not survived. Each entry will also include editorial commentary. Upon completion, the project will have virtually recreated, to the greatest extent possible, an important segment of the visual culture of the city and established the extent of the wealth of such works that were accessible to Philadelphia’s citizens. Historians of all stripes should be able to reach a deeper understanding of the large role that these singular collections played in the cultural and educational life of one of America’s most important cities.

For more information on the project, please contact Director Emeritus John C. Van Horne at jcvanhorne@comcast.net.