Upstairs, Downstairs at the Library Company of Philadelphia

Erika Piola

Curator of Graphic Arts and Director of the Visual Culture Program

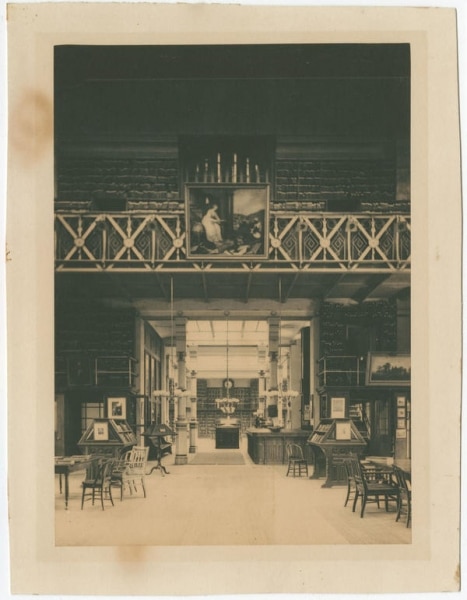

Interior of Library Company of Philadelphia, Locust Street Branch, ca. 1885. Platinum print in Library Company of Philadelphia scrapbook, ca. 1865-ca. 1971.

During the early 1880s, as the Library Company staff “upstairs” assisted readers and received gifts, including more than fifty maps from antiquarian John A. McAllister (1822-1896), janitors “downstairs” maintained our two facilities – the Ridgway Building (Broad and Christian Streets) and the Locust Street Building (Locust and Juniper Streets). Our research for Imperfect History is not only about the graphic materials associated with the Library but the people as well.

In the Library’s archives are a series of monthly reports written by Librarian Lloyd P. Smith (1822-1886) from 1879 to early 1883. Among the content of these records are requests to the Book Committee for permission to purchase titles suggested by or to Smith; orders detailing the month’s expenses; and updates about the functions of the two libraries. All provide glimpses of the everyday lives of the staff at the Library Company. Three of those staff were janitors John Smith and William J. Phillips (Locust Street) and Edward McGrath (Ridgway).

As the Imperfect History curatorial team continues to examine the visual materials received upstairs, we wanted to also explore the stories of the persons who built the cases that housed collections like McAllister’s maps. And who fixed the leaks in the ceilings over reading rooms displaying framed prints, and who worked on the plumbing used by the members who looked at the graphics on the walls and read the books on the shelves (that the janitors also built).

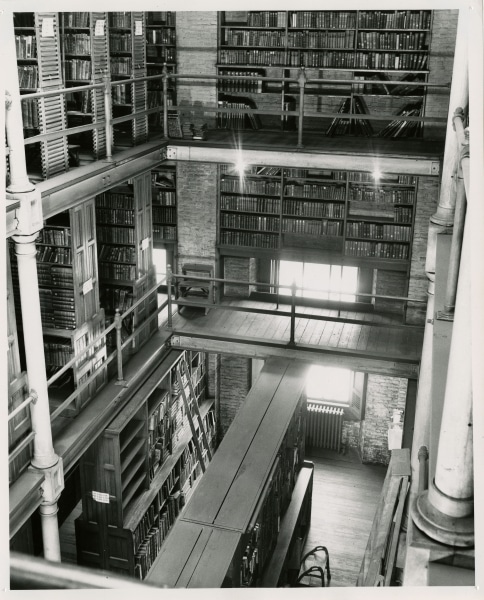

Shelving possibly built by janitor Edward McGrath in the book stacks at the Ridgway Building, ca. 1950s. Gelatin silver print.

By 1880 the Library Company maintained two buildings. The Ridgway Building had been funded and built south of Center City as dictated by the funder and late Library shareholder Dr. James Rush (1786-1869). Soon after Ridgway’s completion in 1878, with its location removed from the residences of most members, the Locust Street Building was erected in 1880 as the “main” library. Near the end of the preceding year, Librarian Smith (LPS) noted that “the time has nearly come to appoint a janitor for the Locust Street Building” (Librarian’s Report, October 1879). By the 1881 reports, a telling narrative of the intertwined work and personal lives of janitors Smith, Phillips, and McGrath is revealed.

The Library Company janitors were men of many trades. Their job title, now most often associated with cleaning, equated to including carpentry, plumbing, and sometimes gardening as part of their work. In return, in 1881, the men received housing and a salary of $50 a month. (Funds in their name for specific project expenses were also noted in the records). The Locust Street janitors Smith and Phillips resided in the basement and McGrath had a “house,” that was an outbuilding on the Ridgway grounds. Like the Library’s history, their housing was “imperfect” as was the Library’s administrative response to addressing their concerns about their lodgings.

By early 1881 signs are evident in the reports that the janitors’ living conditions were not ideal. For McGrath’s residence, the work of making a drain began in March. By the end of the summer, LPS reported to the Executive Committee of “the janitor” (John Smith) at Locust Street, “complaining” again about the “unwholesome character” of his cellar quarters. Concurrently, LPS notes that McGrath at Ridgway asks that the Library pay for his winter coal. He further explains, “His house still does not have a bath or heater to make it comfortable but he does not ask to have it done on account of the expense” (Report to the Executive Committee and Report to the Committee of Ridgway Branch, August 1881).

And by the October 1881 Librarian’s Report, shockingly to today’s reader, he states, “The janitor John Smith having lost two children, which he attributed to the dampness of his quarters in the basement, has resigned his situation .…” Although less dire, the dampness of McGrath’s quarters was mentioned that October as well. Framed in a further “respectful appeal” for his coal to be paid for by the Library as was done “last winter,” McGrath relayed to Librarian Smith, he makes such a request in “consideration of the dampness of the walls and the heavy doctor’s bills he has had to pay” (Report to Committee on Ridgway Branch, December 1881). Unlike John Smith, McGrath would stay with the Library another decade before his services were dispensed with in the months following an 1891 admonishment from the Library for cruelty to his wife (Director’s Minutes, v. 9, 1885-1901).

In the concluding months of 1881, William J. Phillips would replace John Smith. Phillips’s sentiments about his quarters were described as one of no complaint (Report to the Executive Committee, November 1881). However, in the same report, LPS mentioned Phillips received a screen in the garden to dry his clothes and in a later report advocated his “reasonable” request to build closets since there were none in the basement (Report to the Executive Committee, December 1881). From these statements, this researcher cannot help but deduce the janitors’ quarters were “unwholesome,” illnesses were experienced, and there was cause for complaint. Perhaps this is also why in the 1970s a descendant of McGrath returned a pencil, needle case, and scissors the janitor stole from the early 18th-century William Penn’s secretary desk in possession of the Library since about 1844.

Like the Library’s graphics holding that we are exploring through Imperfect History, the Library Company’s archives are also dynamic in their creation. Writing archives and their assembling and study is ultimately a subjective and culturally influenced endeavor despite the most objective intentions in their construction. The persons writing and represented in or by those documents are often not all bad, nor all good. They are imperfect.

Coda:

Two women were on staff during the period written about above. Margaret Gibbs, an African American “scrubber” in employment since the early 1850s, earned $16 a month. Elisabeth McClellan (1851-1920), the first woman Library “assistant,” hired in 1880 earned $40 a month. A niece of Civil War Major General George McClellan, she was author of two books on historic dress in America that were reprinted multiple times during the 20th century after their original publication in the early 1900s.

Imperfect History is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, Walter J. Miller Trust, Center for American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Jay Robert Stiefel and Terra Foundation for American Art.