We Dig: 200 Years of Extraction in the Anthracite Fields of Pennsylvania

Andrea Krupp, Conservator

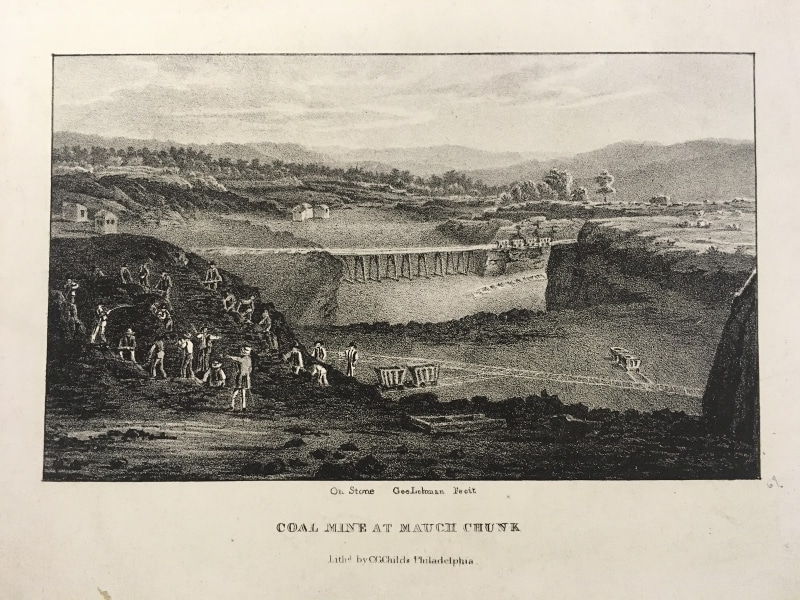

George Lehman, Coal Mine at Mauch Chunk (Philadelphia: C.G. Childs, ca.1837). Lithograph.

Looking through the Library Company of Philadelphia’s Printed Books and Graphic Arts Collections, I am struck by the near ubiquitous presence of coal in 19th-century printed materials. Coal was both a common, everyday material and a cultural presence that signified progress and modernity.

Coal is still a primary source of energy across the globe, but now it stands for the opposite of modernity. Aware, as we are, of the disastrous effects that extracting and burning coal has on the environment, coal has been practically banished from the visual/cultural landscape. Out of sight and out of mind? But coal is full of portent. It is a bellwether material of the Human/Nature/Time relationship which deserves our attention.

In this essay I examine three images that document 200 years of digging for coal in one Pennsylvania location. Historical documents serve an important function by transmitting images of past-place into the present so that we can “see” the passage of time. They provide perspective on changes that unfold incrementally over generations, changes that would be otherwise invisible. Drone photography and satellite imagery literally transform our worldview by extending our vision 100s or 1000s of feet above the surface of the earth, providing an otherwise unseeable perspective on coal sites. Together they demonstrate how the visual places us within a wider context of being – to better understand the world as it is, as it was, and as it might be in the future.

Coal Mine at Mauch Chunk, published circa1837 by C.G. Childs shows a proto-industrial surface coal mine in Pennsylvania. Nineteenth- and 20th-century documents place the mine about eight miles West of Mauch Chunk, called Jim Thorpe today. Over time, the mine has been variously identified as the Great Mine, the Summit Hill mine, or the Old mine. It is located in the coal-rich area of the Southern Anthracite Field, 90 miles North of Philadelphia. Here, geological strata called the coal measures rose from the depths by geological compression to create the ridged, hogback mountains characteristic of the region. At Pisgah Mountain, where Mauch Chunk hunkers at the Eastern end, a massive, 35-70 foot thick coal vein, appropriately named the Mammoth vein, lay practically exposed across the spine of the mountain.

The 4 x 6 inch picture, above, an instructive landscape, portrays a busy coal mining scene happening on a piece of land that has already been drastically altered by extraction. The mine is arranged in carved out “benches” that descend into a multi-tiered, straight-edged pit. In the background, forested hills of the Pennsylvania Appalachian Mountains extend to the horizon. In contrast, the mine land has been cleared of trees, only stumps and tufts of grass remain. In the foreground, a man wearing a waist-coat stands with his back to the viewer. He gestures with his left arm, pointing towards a group of twenty-five workers in front of him. The men climb, dig, carry and stand on a mound of coal, a section of the exposed coal vein. Beyond them, vast mine lands extend into the middle distance. A railway trestle bridge spans a large gap, and a few work sheds dot the cleared land. Railway tracks cross the work site. Two coal wagons stand ready to be filled near the mound, two more sit at a lower level of the pit, and four are stationed at the far end of the railway bridge.

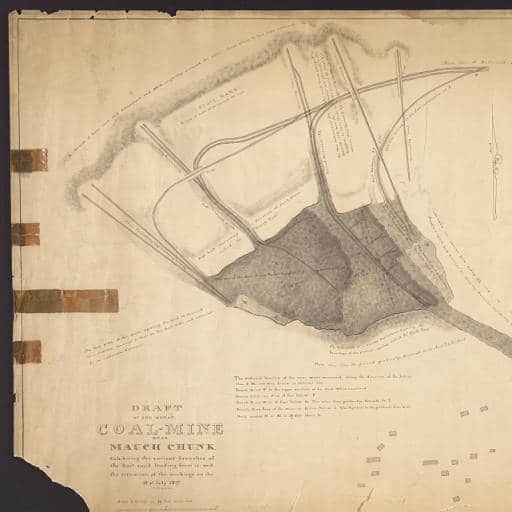

Draft of the Great Coal-Mine near Mauch Chunk exhibiting the various branches of the rail- road leading from it, and the situation of the workings on the 18th of July, 1827. Courtesy of Lehigh University.

This striking technical drawing is part of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company Records that are held at Lehigh University. It shows the same Coal-Mine at Mauch Chunk pictured above as it appeared ten years earlier, when the pit was 38 feet deep. The manuscript, transcribed below, gives interesting details such as the depths of the benches, and notes that dedicated “uncovering lines” were used to haul the top layer of dirt to the culm piles of waste material. A sophisticated horse and gravity rail system moved the coal from the mountain top to the river at Mauch Chunk. Click here or a link to Lehigh University’s Digital Library record.

Below is a partial transcription of the manuscript notes.

Draft of the Great Coal-Mine near Mauch Chunk exhibiting the various branches of the rail- road leading from it, and the situation of the workings on the 18th of July, 1827. I. A.Chapman.

Scale 6 perches or 99 feet to an inch. (note: a perch is a surveyor’s measure equivalent to 16.5 feet)

–

A mound of loose earth and decomposed coal, which originally covered the mine, from which it has been removed.

To this intersection all the road lines [except No.1] descend and here the horses are attached to the waggons to haul them to the summit at slush hill whence they descend by gravity to Mauch Chunk.

High bank containing a Stratum of sand-stone called the “North Fort”

On this side is a narrow Sandstone forming the boundary of the present opening, called the “South Fort”

From this line the ground gradually descends to the North + to the South

-A This part of the mine forms the bottom or floor of the peresent (sic) workings.

B This bench is about 15 to twelve feet above the bottom floor marked A.

C This bench is about 16 feet above the bench marked B

D This bench is about 10 feet above the bench marked CCC

–

The different benches of the mine were measured along the direction of the dotted line FM and were found as follows viz:

Bench D at F is the upper surface of the coal when uncovered.

Bench CCC at G is 16 feet below F

Bench B at H is 15 feet below G. The mine then gradually descends to I

Bench A, or floor of the mine, is 18 feet below I. The descent is gradual from K to I

Bench marked N at M is 39 feet above L.

Both 19th-century images project expertise, pride, American grit, and entrepreneurial spirit. From a 21st-century perspective, they also reflect a naive enjoyment of the illusion of nature as an inexhaustible storehouse for extraction. In the Childs’ lithograph the contrast between the mined and natural landscapes is jarring. It reminds us that the intangible and discounted costs and losses of present-moment actions are borne by future beings.

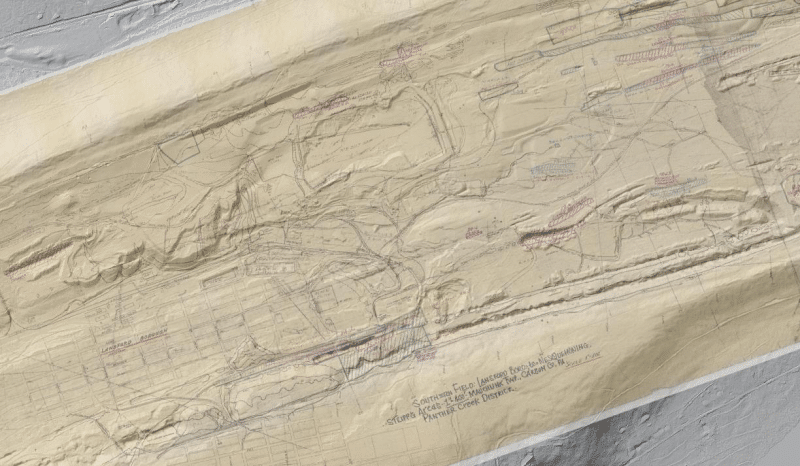

Screenshot from https://www.minemaps.psu.edu showing the location of the Great Mine on Pisgah Mountain overlaid with an early 20th-century strip mining map.

Satellite and drone imagery bring a radical new perspective to how we perceive the land, and reveal patterns that would not otherwise be seen. From a bird’s eye view, the extent of our digging on Pisgah Mountain becomes shockingly visible. The complex layering of pit, drift, and deep mines, and their attendant culm piles and industrial infrastructure is a palimpsest of human/coal entanglement across time.

Compared to coal’s prominence in the 19th century, coal is much less visible today. Seen together, historical and contemporary images of coal and coal sites help us to keep coal in view as we assess and re-imagine our relationship with it, with Nature, and with the

future.

This essay is based on my research for my upcoming exhibition Seeing Coal – Time, Material and Scale that will be on display at the Library Company of Philadelphia May 3 – August 28, 2021. The exhibition features Pennsylvania anthracite coal and examines the significance of its visible and invisible presence in our world. Through historical images, material specimens, artwork, and digital displays, coal is presented as a material that can help us re-think our relationship with nature and time, and act with consideration for future generations.

![Wilkinson after John Singleton Copley, [The Wretched State of the Nation] (Philadelphia, January 20, 1766). Etching. Pierre Eugene Du Simitière Collection.](https://librarycompany.org/wp-content/uploads/Cartoon1766Wre-395-F-3-80x80.jpg)