Minding the Gaps

Erika Piola

Curator of Graphic Arts and Director of the Visual Culture Program

Wilkinson after John Singleton Copley, [The Wretched State of the Nation] (Philadelphia, January 20, 1766). Etching. Pierre Eugene Du Simitière Collection.

The core theme of the Imperfect History exhibition is the evolution of the curation and content of the graphics arts collection over the Library Company’s nearly 300-year history. I have worked with these holdings for over twenty years, including over ten of those as a curator. Like the collection and its curatorship, my knowledge and understanding of the collecting scope of the materials has gone through an evolution as well.

When conceiving the Imperfect project, I was aware that in studying these evolutions I would necessarily become even more conscious of the gaps within our collections in terms of subject matter, cataloging, and accessibility in relation to its scope. This post is born from this deliberately and sometimes uncomfortable introspective work.

In defining the mission of a special collection library a “scope of collections” statement is necessary. In essence, the statement describes what materials the library or a department in the library collects and why. When the Graphic Arts Department was established as the Print Department in 1971, then Librarian Edwin Wolf described the overall scope of the collection as the “flatware” among the Library’s book and other textual holdings. The flatware was born from hundreds of years of passive collecting (or more rightly receipt) of graphic material by Library administrators. The collection began to take a more focused direction when the Library changed from a public to an independent research institution in the 1950s.

Until that time a potpourri of unevenly documented graphics arrived at the Library, mainly as gifts, beginning in the 1730s. Subject matter of the materials ranged from a portrait/advertisement received in 1790 of an enslaved Black man displayed as a human curiosity in London to early stereographs of the construction of City Hall donated in the early 1870s to a “scrapbook of portraits from magazines” given in 1939. Although a seeming hodgepodge of visual works, inklings of the scope of the graphic arts collection was crystalizing. A crystallization that was also informed through purchases. The Library bought American Revolutionary cartoons collected by Swiss historian Pierre Eugene Du Simitière (ca. 1736-1784) in the late 18th century and photographer John Moran’s (1831-1903) views of the changing cityscape of Philadelphia in 1870. By consequence, the Graphic Arts Department is today a premier collection for the study of the visual culture of the early nation and of Philadelphia to the mid-20th century. But as with any collection, there are gaps in what has been collected – intentionally and unintentionally – that are rooted in the Library’s history and sociocultural role in the nation and city’s visual culture.

Nathaniel Currier, Wm. Penn’s Treaty with the Indians, when he Founded the Province of Pennsa. 1681 : The Only Treaty that was Never Broken (New York: Lith. & pub. by N. Currier, ca. 1845). Hand-colored lithograph.

One way this has been made evident is with the Department’s images of Indigenous peoples. Unlike our African American and Black history graphics holdings, the depiction of the Native American community has not been a proactive focus for our visual material collecting. The recent Ghost River project highlighted political cartoons from our graphic arts collections documenting the genocide of Conestoga people near Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 1763. However, a significant number of our depictions of the local Native American community are variant prints of the imagined view of William Penn’s treaty with the Lenni-Lenape people after the 1771 painting by Benjamin West (1738-1820). The works were predominately acquired over the 20th and 21st century. This absence speaks to the gap in Philadelphia visual culture of non-imaginary, historical visual records of the Indigenous people of our region; the effects of settler colonialism to make a community invisible; and the consequence of a delimited interpretation of local Native American history in alignment with our collecting focus. It also raises questions: do we and how do we address this gap? Proper due diligence and consideration needs to be employed, including mindfulness of the collecting focuses and subject expertise of our peer institutions, who may be more appropriate repositories of local Indigenous visual culture. We continue to search for answers.

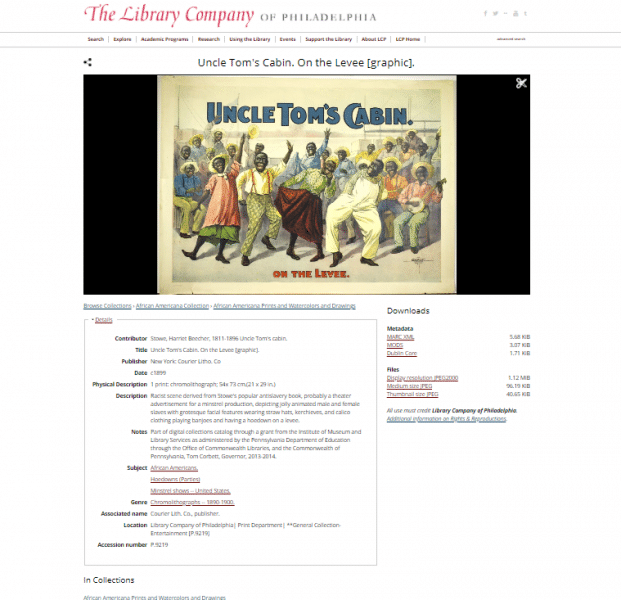

Screenshot of African American history graphics catalog record for a racist 1899 theater advertisement.

Gaps in our curatorial work have also been uncovered in how we have provided access to our African American history graphic materials. Online catalogs, digital and traditional, are central to the access of graphic art through searches of titles, artists, descriptions, and subject headings. A part of our online catalogs for decades now, our African American history graphics records are overdue for remediation of vocabularies in contradiction with antiracist language and in need of further contextualization for their harmful and offensive content. Words used in curatorial descriptions are not neutral because they are historical. Nor are subject headings inoffensive because they are standardized. And although our African American history holdings have been consistently and conscientiously cataloged, it is time to revisit and revise these catalog records of graphics that are often racist in content and visually document the lives of enslaved men, women, and children. In this case, we have an answer. We will begin to revise these records this year.

Curatorial decisions about the scope of a collection and the resulting gaps can be organic, deliberate, or in response to evolving research focuses of the users of a special collection. In addressing these gaps as graphics curators, we often grapple with questions of scope in terms of context and content in what is acquired during our, as well as our predecessors’ tenures, as stewards of history. This responsibility includes our knowing when it is an appropriate, or a necessary, or a well-intentioned, but misplaced inclination to preserve and provide access to the visual history of a community that may be better served through the care of another institution. A goal of the Imperfect History project is for visitors to realize what can be learned from the “unseen” in the historical visual material collected since the colonial era by a centuries-old institution. The current curators of these materials are also ones who continue to learn this.

Imperfect History is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, Walter J. Miller Trust, Center for American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Jay Robert Stiefel and Terra Foundation for American Art.

![Wilkinson after John Singleton Copley, [The Wretched State of the Nation] (Philadelphia, January 20, 1766). Etching. Pierre Eugene Du Simitière Collection. Wilkinson after John Singleton Copley, [The Wretched State of the Nation] (Philadelphia, January 20, 1766). Etching. Pierre Eugene Du Simitière Collection.](https://librarycompany.org/wp-content/uploads/Cartoon1766Wre-395-F-3-800x527.jpg)

George Lehman, Coal Mine at Mauch Chunk(Philadelphia: C.G. Childs, ca.1837). Lithograph.

George Lehman, Coal Mine at Mauch Chunk(Philadelphia: C.G. Childs, ca.1837). Lithograph.