During Fall 2020, Erika Piola, Curator of Graphic Arts and Director of the Visual Culture Program had the pleasure to work with Temple University Assistant Professor of American Art Erin Pauwel’s class Art & Spectacle in the 19th-Century United States. The class entailed object lesson presentations based on graphic arts holdings in the Library’s collections. The sessions facilitated students’ research of a visual material from these holdings and culminated in student podcasts, virtual presentations, online exhibitions, and the following blog post by Emily Schollenberger whose study focused on the 1896 mixed media album Memories of the Homes of Grandma Lewis.

Albums as/in Archives: Whose Identity is Preserved?

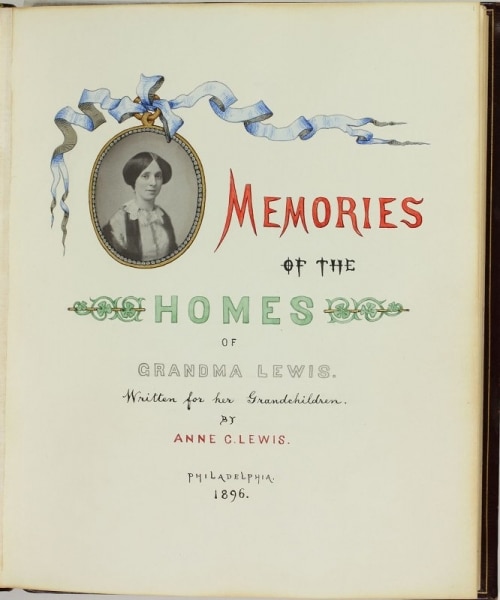

Anne C. Lewis, Frontispiece in Memories of the Homes of Grandma Lewis, 1896. Library Company of Philadelphia, P.9829.2.

From its hand-painted frontispiece to lavish watercolors of parlors and libraries, Memories of the Homes of Grandma Lewis provides a wealth of information about life in 19th-century Philadelphia. Made by Philadelphia resident Anne C. Lewis (1831-1898) for her grandchildren in 1896, the album contains photographs, scraps of clothing and upholstery, hand-painted decorations, watercolors of the Lewis homes’ interiors, and pages of Lewis’s elegant handwriting. Her writing provides context for the album’s visual material, tempting present-day readers to view her album as a transparent record of family life in Philadelphia. However, as photography historian Shawn Michelle Smith argues, even seemingly innocuous conventions, like treasuring photographs of babies, can perpetuate some people’s stories at the expense of others. As we peruse Anne Lewis’s album, faint hums become apparent in the pauses in her narrative, hinting at other lives and memories adjacent to the Lewis family. In the language of Tina Campt, these whispers of other lives are “lower frequencies” that must be felt rather than heard. In order to feel the lower frequencies that resonate alongside Anne Lewis’s eloquent voice, we must consider the larger context of the family album as personal archive as well as its place within an institutional archive.

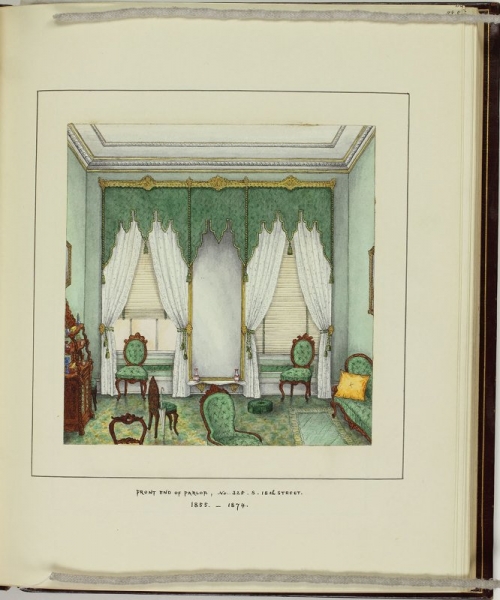

George Albert Lewis, “Front End Parlor,” in Memories of the Homes of Grandma Lewis, 1896. Watercolor, Library Company of Philadelphia, P.9829.2.

Family albums like Memories of the Homes of Grandma Lewis form private archives that preserve their maker’s memories for future readers. In the late 19th century, ornate family albums like the Lewis album were not only archives for family history, but also objects of display for guests. An 1896 article in Godey’s Magazine pokes fun at the family album, calling it a sacred household god and noting the “ostentatious reverence” with which it would be paraded before visitors. Displaying albums in parlors signified gentility and furnished a pattern for social interaction between hosts and guests. Album making was also accessible to less prosperous people. Thanks to the abundance of printed material in late 19th-century America, almost anyone could make a personal archive in the form of a scrapbook of newspaper clippings or other printed material. Although these albums existed for years, many institutional archives like the Library Company of Philadelphia did not begin collecting them until recently. For the most part, only albums that were considered significant because of their artistic quality or their creator’s status were preserved in institutions. Anne Lewis’s scrapbook enjoyed both of these advantages. The album is beautifully made and she and her husband frequented prestigious social circles. A descendant of the family, Oliver Allen, donated several Lewis albums to the Library Company of Philadelphia in 2000, ensuring their preservation in an institutional archive. Because of these factors, the subjectivity of affluent white families like the Lewises often has a larger presence in historical archives than that of more marginalized people.

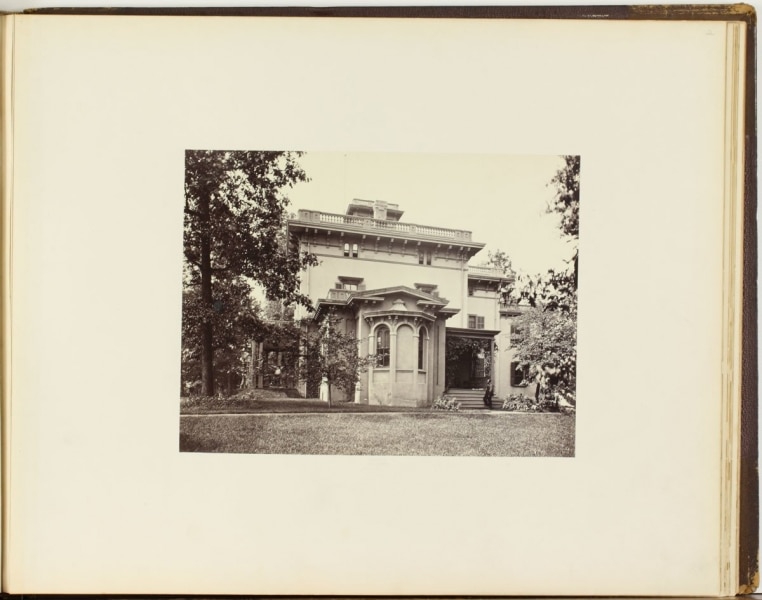

Robert Newell, Page 2 in Views at Chestnutwold, Residence of C.H. Clark, ca. 1870. Albumen print mounted on cardboard, Library Company of Philadelphia, P.9291.

While the album centers around the Lewis family and their social circle, hints of other Philadelphia residents emerge in its pages. The Lewis family’s comfortable lifestyle required the work of people who are largely visibly absent from the album. The family’s coachman Amos is one example. Anne recalled taking her infant daughter Alberta with her on shopping excursions because she did not have a trustworthy maid to watch the baby. She wrote that “Amos, the colored coachman, was very fond of the baby,” and that when she went into stores she would leave Alberta asleep on the carriage seat, where Amos would watch her and drive up and down the block to soothe her if she woke up. In a companion album, Anne’s husband George Albert Lewis also mentions Amos and describes him as “a large and stately old servant with iron gray hair, who sat his box with great dignity.” These brief verbal mentions of Amos are the only record of him in the albums, in contrast to the extensive visual record of the Lewis family and their homes. In the Lewis album, Amos fills a similar purpose as the African American servant pictured in the Philadelphia banker Clarence Howard Clark’s album of 1870. This man stands on the steps of Clark’s residence, his stature small beside the spacious house. Both this unnamed man and Amos appear as props to a white family’s comfortable life, rather than as individuals whose thoughts and memories should be recorded.

Portrait of Harmon Richardson in Portrait Album of Well Known 19th-Century African American Men of Philadelphia, 1865-85. Albumen print, Library Company of Philadelphia, P.9304.

Although Amos’s presence is only a faint hum in the Lewis albums, and in the larger institutional archive of the Library Company, African American Philadelphians in the latter half of the 19th century did record their own inner lives in albums. The Black Philadelphia resident Joseph W. H. Cathcart compiled over 130 scrapbooks, making a massive archive of his own. He started making scrapbooks in the 1850s, at the same time that Amos was soothing baby Alberta to sleep during her parents’ shopping trips. Like Amos, Cathcart did not occupy a prestigious position in Philadelphia society. For decades, he worked as a janitor in an office building, clipping items relating to Black life from newspapers and compiling them into album after album. Although his albums’ contents are very different than Anne Lewis’s album, his selection of newspaper items forms an archive that reflects his thoughts. Another album in the Library Company’s collection, compiled between 1865 and 1885 contains photographs of well-known African American men. No annotations elucidate the maker’s identity or thought process, but nevertheless the album preserves a glimpse of what one Black Philadelphian valued in the late 19th century. Like this person and like Cathcart, Amos could have made his own personal archives by compiling photographs or news articles into scrapbooks.

The abundant textual and visual material in the Lewis albums threatens to overwhelm the other voices that vibrate below Anne’s narration. Considering other kinds of scrapbooks and the role of albums in archives can help contemporary readers attend more carefully to the lower frequencies that run beneath Anne’s voice. Readers in archives today cannot necessarily recover the thoughts, feelings, and memories of Amos or any of the other domestic servants who made up the Lewis household. But by being aware of the album’s original function and its current location in an archive, readers can more closely listen to the hum of the other voices that occupied Grandma Lewis’s homes.

Sources

Allen, Oliver E. “The Lewis Albums.” American Heritage (1962): 65-80.

Campt, Tina. Listening to Images. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017.

Garvey, Ellen Gruber. Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Langford, Martha. Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001.

Lewis, Anne C. Memories of the home of Grandma Lewis: Written for her grandchildren by Anne C. Lewis. Philadelphia, 1896. Library Company of Philadelphia, P.9829.1.

Lewis, G. Albert. The Old Houses and Stores with Memorabilia Relating to Them and my Father and Grandfather, Philadelphia: 1900. Library Company of Philadelphia, P.9829.2.

Raphael, Rudolph. “The Family Album.” Godey’s Magazine 132 (1896): 318. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Godey_s_Magazine/_Vg2AQAAMAAJ?hl=en& gbpv=1.

Smith, Shawn Michelle. “’Baby’s Picture is Always Treasured’: Eugenics and the Reproduction of Whiteness in the Family Photograph Album.” The Yale Journal of Criticism 11, no. 1 (1998): 197-220.

Vosmeier, Sarah McNair. “Photograph Albums and Networks of Affection in the 1860s.” In The Scrapbook in American Life, edited by Susan Tucker, Katherine Ott, and Patricia P. Buckler, 207-219. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2006.