Fitz-Greene Halleck: The Most Famous Gay Poet You’ve Never Heard Of

For the Library Company’s 2021 LGBTQ History Month program, Dr. Jordan Alexander Stein, Professor of English at Fordham University, spoke about the 19th-century poet Fitz-Greene Halleck.

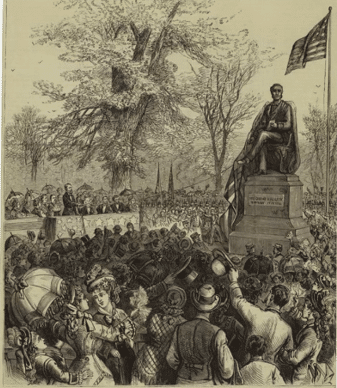

In May 1877, when President Rutherford B. Hayes unveiled a bronze statue of Fitz-Greene Halleck (1790-1867), the crowd of about 10,000 people did so much damage to Central Park that New York passed an ordinance limiting the size of future events.

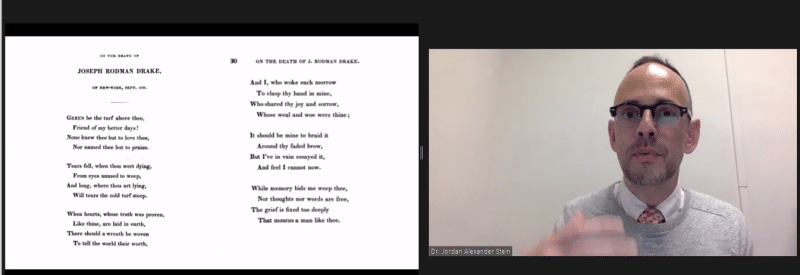

Early in his career, Halleck collaborated with the writer Joseph Rodman Drake on satiric verse that appealed to culturally savvy New Yorkers for its wit. Drake’s death in 1820 became a turning point. Halleck’s elegy on the death of Drake established his reputation as an accomplished poet. Reading the poem, Prof. Stein noted the musicality of its repeated sounds, and also noted the intimacy in the lines “And I who woke each morrow / To clasp thy hand in mine, / Who shared they joy and sorrow, / Whose weal and woe were thine.”

Other poems that were published following Halleck’s own death also express love and longing for men. Prof. Stein noted that New York’s emerging gay male culture was not under much scrutiny until later in the century. Anti-vice sentiment and legislation generally focused on female prostitution, and not on the male prostitution that existed in areas such as the Bowery. Both Halleck and Walt Whitman (1819-1892) reportedly frequented Pfaff’s, a bar in Greenwich Village known for having female impersonators and “bohemians” among its clientele. The cautionary texts about sexual deviance that did appear in contemporary periodicals such as the Whip could easily be read as informational.

As a poet, Halleck was most prolific in the 1840s. After his death in 1867, his verse came to represent Old New York for writers such as Edith Wharton. The bronze statue of Halleck that was unveiled in 1877 is unusual in that it depicts him with his legs crossed, a pose that might have been coded “gay” in the 1870s. Similarly, a 1980 article in the New York Times mentions his “teacup fingers.” To dramatize how extremely unusual Halleck’s statue was in its time, Prof. Stein showed Emma Stebbins’s roughly contemporaneous statue Angel of the Waters (also in Central Park, and notably … the work of the female sculptor who was Charlotte Cushman’s partner).

Today, there is a resurgence of interest in both Halleck and 19th-century poetry in general. Gay men in New York often leave flowers in the “teacup fingers” of the statue on Halleck’s birthday on July 8th, and after decades of poetry being understudied, many scholars are revisiting the genre with fresh eyes.

At the Library Company, we have many volumes of poetry on our shelves, some of which clearly (or somewhat clearly) articulate an LGBTQ sensibility. We look forward to more opportunities to support research in this area. In the meantime, do visit the statue of Fitz-Greene Halleck when you’re in Central Park.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (June 2, 1877)

The full lecture is available on YouTube, or embedded below.