The following post was written by Imperfect History Digital Catalog guest cataloger Clayton Lewis about his experience. The Catalog creatively engages with the Imperfect History exhibition themes of (un)conscious bias and multiple viewpoints. Four guest catalogers from the curatorial, art history, and studio art fields authored concise descriptions of the same visual material, from their individual perspective as affected by their discipline. A traditionally standardized, “objective” process was made pro-actively subjective and diverse.

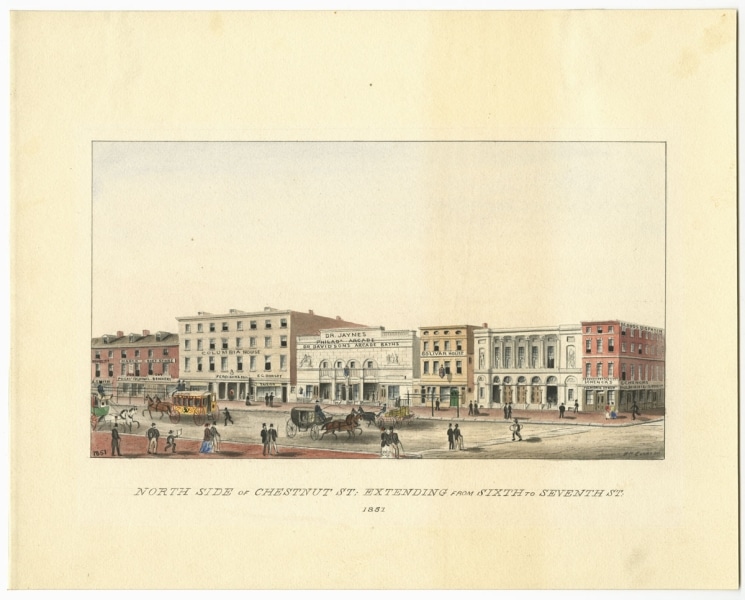

Benjamin Ridgway Evans, North Side of Chestnut St., Extending from Sixth to Seventh St., 1851 (Philadelphia, ca. 1880). Watercolor.

Imperfect History Project

Inherent in institutions such as The Library Company of Philadelphia and the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan, where I work, are tensions between established information access systems and the multicultural America that our materials document. For me, the images selected for description in the Imperfect History project brought these issues to the fore.

Existing archival practices have enormous inertia coming from shared use on a massive scale. Libraries rely on uniformity within our shared systems so cross-institutional access is possible. We are obligated to cooperate with existing universal library access systems, as obsolete as they may be, or risk becoming invisible to search queries. This condition inhibits much in the way of progressive change, but it is still possible to work towards better, more equitable access to information. I applaud the Library Company for advancing awareness of these issues through Imperfect History and other programs.

Among the many long-standing and troubling institutional policies related to describing collection materials is the presumption of a white male baseline. Materials related to African American subjects, for example, are especially tagged as different from the norm, as are Native American, female, Latinx, and countless other topics. This of course has the effect of “othering” non-white male subjects because whiteness is the default “normal.” These identities are of course critical for scholarship and cultural understanding. Is there a way that racial, ethnic, gender, and other identifying characteristics can be used equitably within existing cataloging standards? One solution is to not use these terms at all; but to ignore identity distinction is to ignore the problem. Assigning a racial and gender identifier to all cataloging has been experimented with at the Clements as a means of addressing this inequity, but this too falls short because it operates on binary principles that disregard more nuanced concepts of identity. Furthermore, we often are mistaken when presuming identity. We can’t be certain all the time.

During the cataloging phase of this project I found that the materials presented for Imperfect History are deeply meaningful in ways that we can only hint at within a typical library catalog record. One example offers a view of a thriving community of established urban commerce that also raises questions about what is not represented; another codifies mainstream behavior, roles, and societal structures for a mass audience; another example challenges the stereotypes of race that dominated the 19th century. Each of these is also instructive about the baseline normalcy within institutional cataloging and classification systems.

The watercolor North Side of Chestnut Street Extending from Sixth to Seventh St. 1851 by Benjamin Ridgway Evans presents a nostalgic look at Philadelphia’s urban scene of the 1850s. The emphasis is on the businesses that occupied the storefronts and the atmosphere of mercantile activity. For a museum or library cataloger, this orderly streetscape could be considered an example of baseline whiteness. No racial classifications like “African American business enterprises” are needed here. This is a historical view of the “normal” America that our institutional systems were designed to describe.

The lithograph The Life and Age of Man. Stages of Man’s Life From the Cradle to the Grave, by Nathaniel Currier comes from the center of mainstream Protestant American values. It establishes ideals and benchmarks while charting the course of life for a white male American. It is both a cultural product and behavioral roadmap. What if it included references specific to say, Irish Catholics? Chances are that may be called out by an alert library cataloger as something notable and shift this object and what it represents a few degrees away from the center.

The daguerreotype of an African American woman seated in a window-frame taken by Samuel Broadbent is a terrific example of how the commonplace genre of portrait photography could become a radical statement of inclusion and determination. For a museum or library cataloger, the presence of the African American subject is central to the cultural value and meaning of this object and would be prominent in any description or classification. Libraries anticipate that scholars of race and visual culture will go out of their way to study images of this type. Our cataloging and collection sorting reflects this. It seems a simple enough decision to group similar materials together to ease access for our library patrons and to streamline the paging of materials by staff. We have frequently experienced patrons that simultaneously request all of our early photos of African American subjects. But if we cluster all of these similar materials into a single collection, have we then created a segregated community? What does this signal about where the baseline of normalcy is within our institution?

As librarians, what can we do to achieve equitable description and access? We can be alert to and respectful of cultural diversity. We can strive for more equitable information access systems. When dealing with cultural representations, consult with those of that culture when possible. Share what you know but be aware of our own biases. And support sincere programs to address these issues such as Imperfect History.

Clayton Lewis, Curator of Graphic Materials, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan

Imperfect History is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, Walter J. Miller Trust, Center for American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Jay Robert Stiefel and Terra Foundation for American Art.