The following post was written by Imperfect History Digital Catalog guest cataloger Lauren Hewes about her experience. The Catalog creatively engages with the Imperfect History exhibition themes of (un)conscious bias and multiple viewpoints. Four guest catalogers from the curatorial, art history, and studio art fields authored concise descriptions of the same visual material, from their individual perspective as affected by their discipline. A traditionally standardized, “objective” process was made pro-actively subjective and diverse.

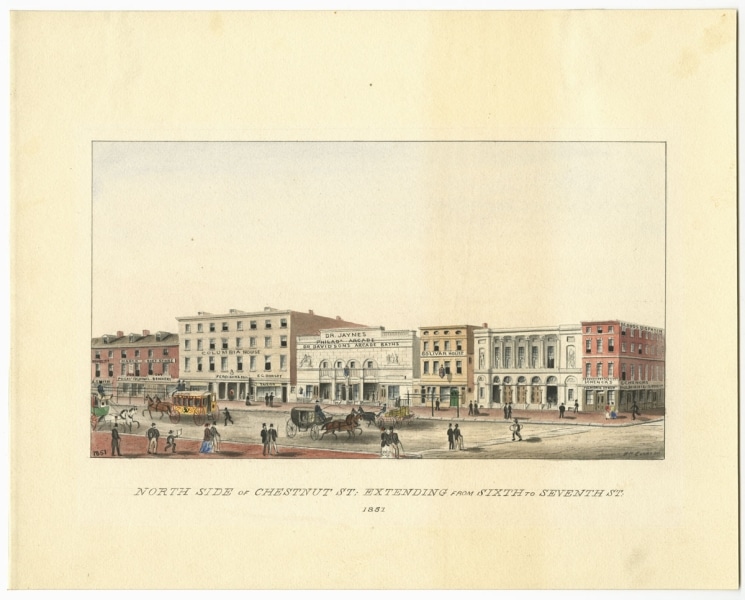

Fig. 1. Benjamin R. Evans, North Side of Chestnut St., Extending from Sixth to Seventh St., 1851, ca. 1880. Watercolor on paper. Library Company of Philadelphia. Gift of Girard Bank and the Friends of the Library Company, 1975.

Visual Antiquarianism

As I researched Benjamin R. Evans’s watercolor North Side of Chestnut St., Extending from Sixth to Seventh St., 1851, (fig. 1) painted around 1880 for the retired Philadelphian jeweler Ferdinand J. Dreer (1812-1902), I came across references to Dreer as an ‘antiquarian’ in the period press. As a curator at the American Antiquarian Society (AAS), a national research library located in Massachusetts, I am particularly attuned to the word ‘antiquarian.’ It is defined today by Merriam Webster’s as “one who collects and studies antiquities.” Antiquities in turn, have been famously described by British philosopher Francis Bacon as “the remnants of history” which are rescued when “industrious persons, by an exact and scrupulous diligence and observation of monuments, names, words, proverbs, traditions, private records and evidences, fragments of stories, passages of books …, and the like, do save and recover [them] from the deluge of time.”[1]

Fig. 2. Bass Otis, Self Portrait at Age 76, 1860. Oil on tin. Inscribed on reverse by the artist: “Bass Otis / Painted by himself / Aged 76 / For F. J. Dreer, AD 1860.” American Antiquarian Society. Gift of Charles Henry Taylor, Jr., 1928.

I know Ferdinand J. Dreer first and foremost as a patron of the arts. He commissioned a self-portrait from Philadelphia lithographer Bass Otis (fig. 2) now held at AAS. Dreer is known best, however, as a collector of manuscripts, particularly letters written by the famous and infamous. He is also known in the library world as an extra-illustrator (or Grangerizer)—a person who rebound existing historical texts with a variety of inserted material intended to augment the original.[2]

As I was writing the entry for Imperfect History, I found myself grappling with revisionist aspects of the Evans watercolor. The scene is one of a set of images of “old” Philadelphia reconstructed by the artist, who drew on source material from the 1850s to reimagine the past. But in many of the views, Evans left out free Black and immigrant populations, and he tidied up commercial clutter and signs of urban decay. I had a lot of questions that I could not answer by looking at the object, or with the archival resources available. Were the revisions initiated by Evans or directed by the patron Dreer? Should the series of watercolors by Evans be considered as a visual equivalent of Dreer’s extra-illustrated texts—essentially views augmented and “improved” (whether under the direction of Dreer or not) to present the city’s past in a certain, imperfect way?

Fig. 3. The Antiquarian (Boston: Senefelder & Co., 1830 or 1831). Hand-colored lithograph. American Antiquarian Society.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, antiquarianism proudly focused on actual historic materials, using those “remnants of history” as empirical evidence to reveal information about the past. By the latter half of the 19th century, when Evans was making views for Dreer, the term ‘antiquarian’ was also being used in a pejorative way. Cartoons (fig. 3) and stories making fun of grey-haired, male enthusiasts collecting trivial scraps of manuscripts, bits of sculpture, and old books circulated throughout the United States and Europe. Antiquarians were often depicted as myopic, irrational, unable to see context, and obsessed with details that the rest of society deemed irrelevant.[3]

In the end, many of my questions remain unanswered. Was Dreer rescuing an idea of old Philadelphia from the “deluge of time” by commissioning Evans’s watercolors? Or was he being looked at askance by his peers for spending his money on idealized views of the past just as the city was exploding into the modern era with new transport hubs, gas lights, and telegraph lines? The whole process of considering the watercolor and the term ‘antiquarian’ also made me wonder—as an employee of an Antiquarian Society—which am I? I certainly work hard to be one of Bacon’s “industrious persons” using “exact and scrupulous diligence” to preserve all remnants of history for future citizens to consider, but I recognize that I, like Dreer and Evans, have bias, whether explicit or implicit, built into my curatorial approach. I thank my colleagues at Library Company of Philadelphia for creating the Imperfect History project to help me recognize and address those biases.

Lauren B. Hewes, Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Graphic Arts, American Antiquarian Society

[1] Francis Bacon, “Of the Proficience and Advancement of Learning, Divine and Human, Book Two,” 1605. In The Essays of Lord Bacon (London and New York: F. Warne & Co., 1889); 178.

[2] AAS has one extra-illustrated book attributed to Dreer—today, the majority of his manuscript collection and extra-illustrated volumes are housed at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

[3] For more see Anne A. Verplanck, “Making History: Antiquarian Culture in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 138, no. 4 (October 2014): 395-424.

Imperfect History is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, Walter J. Miller Trust, Center for American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Jay Robert Stiefel and Terra Foundation for American Art.