Chinatown: The History of a Philadelphia Neighborhood

Linda Kimiko August, Curator of Art & Artifacts & Visual Materials Cataloger

Parade in Chinatown…Chinese School Children Lead Parade Carrying Banners, etc. (Philadelphia, 1937). Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Philadelphia’s Chinatown, located a few blocks from the Library Company, is a vibrant and active neighborhood that has evolved since its founding in the 19th century. Its history includes instances of perseverance and achievement in the face of perils from voyeurism, harassment, and destruction. The community remains resilient in spite of many changes over the years. The roots of Chinatown began in the 1870s when Chinese people moved east to flee the growing racism and violence in the American west.

After the Civil War, Americans began to blame Chinese laborers for economic problems. Essential in mining and building the transcontinental railroad, these workers started to be labeled as competition for jobs. Political rhetoric increasingly focused on immigrants as a threat and advocated the deportation of Chinese people and prohibition from entering the country. Over 150 violent massacres and riots targeted Asian people in the West, including in Los Angeles and San Francisco. This illustration captures the horrific mob violence in Denver. Rioters destroyed twenty-three homes and beat and brutalized the Chinese residents, including hanging one man over his front door.

N.B. Wilkins, “Colorado. The Anti-Chinese Riot in Denver, on October 31st,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (November 20, 1880).

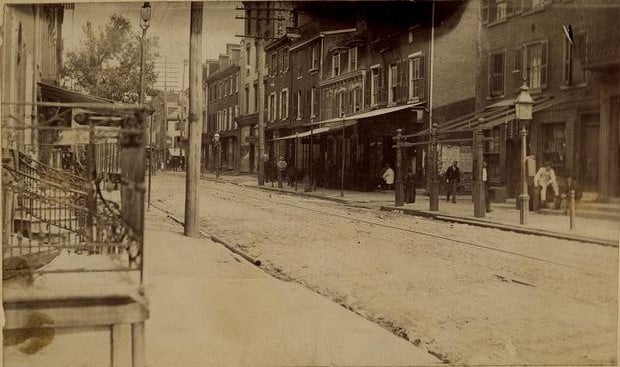

Chinese people began moving to the east coast into cities like Philadelphia to escape the wave of anti-Asian violence. An 1876 article in the Philadelphia newspaper, The North American, reported on the increase of Chinese into the city, “we do not know the actual facts respecting the movements of Chinese emigrants from the Pacific coast to the Atlantic States, but if we may judge by what we see every day in the streets of Philadelphia, it must have been quite considerable.”[1] Chinatowns formed out of necessity because of racial discrimination in housing and employment. White Americans segregated people of Asian descent into ethnic enclaves and further restricted the kinds of work they could perform. Chinese people relied on creating their own small businesses, such as laundries, grocery stores, restaurants, and shops selling import and export goods. The nucleus of Philadelphia’s Chinatown centered on the 900 block of Race Street. The buildings typically consisted of a first-floor storefront business with living quarters on the stories above.

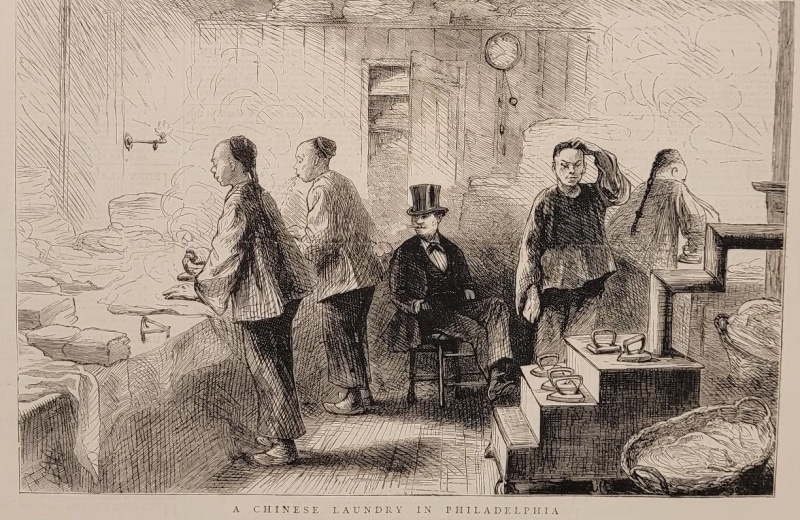

Laundries in Chinatown began opening in Philadelphia in the 1870s, and the North American stated that, “their laundry enterprises have been quite successful.”[2] The Graphic supplied a description with an engraving of such a business.

“There are several Chinese laundries in Philadelphia, and they have only recently been introduced from California, they are almost as much objects of interest to Philadelphians as to foreigners. Our artist came across the laundry shown in our engraving unexpectedly. As soon as the Chinamen perceived him sketching it through the window, they rushed out and shouted after him, whereupon he made off thinking it prudent to avoid a scene. The Celestial in European dress is the “boss,” or master, who owns several laundries, and who attends to the customers and business arrangements.”

“A Chinese Laundry in Philadelphia,” The Graphic (June 3, 1876). Gift of Linda Kimiko August.

Clearly, the laundry workers did not appreciate the voyeurism of the artist. From the description, it seems Philadelphians regularly acted with this kind of curious and intrusive behavior. Concurrently, tensions arose repeatedly between Chinese men laboring at “women’s work” and the discriminatory practices that forced them into these occupations and prevented them from entering other fields.

Race Street (Circa 1890). Store With Sidewalk Covering, Next to Small Street or Alley is Quong Yeun Chong & Co. 922 Race St., Chinese Groceries and Novelties (Philadelphia, ca. 1890). Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Philadelphians’ view of Chinatown soon changed from a site of curiosity to one of danger that needed to be surveilled and policed. Numerous arrests and raids appeared in newspaper reports in the 1880s and 1890s. Chinese people faced harassment and discrimination, including for merely standing outside in their own neighborhood. In 1887, seven Chinese men signed a statement protesting their treatment after arrests were made and notices put up in Chinatown warning Chinese people it was unlawful to gather or stand on the street. The petitioners ardently wrote, “that it is natural for human beings to do so, and that it is done by Americans … they have rights which should be respected as long as they behave themselves ….” The petitioners charged “their Christian neighbors” with “inciting prejudice against them of doing them violence.”[3] The enforcement of blue laws, which prohibited certain activities on Sundays, were used to close businesses in Chinatown and fine owners and operators, including those that sold medicine.[4]

Violent attacks perpetrated against Chinatown residents made people unsafe even in their own neighborhood. Examples include three drunken white men wielding a knife and throwing stones in the shop of Kee Wing, and George Clark, a twenty-four-year-old white man, who “abused the occupants” at 923 Race Street and “became so disturbing that he was locked up.” [5]

Growing anti-Chinese sentiment resulted in the passage of the first laws in the United States to specifically target an ethnic group, including the Page Act in 1875 which prohibited Chinese women from entering the United States, and the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which barred further immigration and declared Chinese immigrants ineligible for naturalization. The Geary Act of 1892 required Chinese people to carry a registration certificate or face one year of hard labor or deportation. Philadelphia District Attorney Ellery P. Ingham used the Act to make arrests, including restaurant cooks Yung Wung and Lee Gin and laundry workers Lee Kee and Hong Butt. Ingham maintained that they all illegally came after 1882 and as laborers they were not entitled to residence here, even those, who like Hong Butt, did have registrations papers.[6] Fear spread through the community, and Chinese residents began registering to try to avoid arrest.[7]

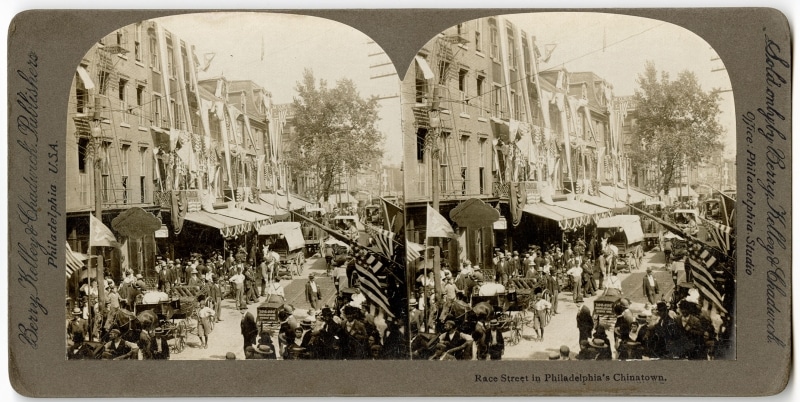

Berry, Kelley & Chadwick, Race Street in Philadelphia’s Chinatown (Philadelphia, ca. 1900).

Despite this, Chinese residents still strived to live, work, and maintain their culture as Asian and American.

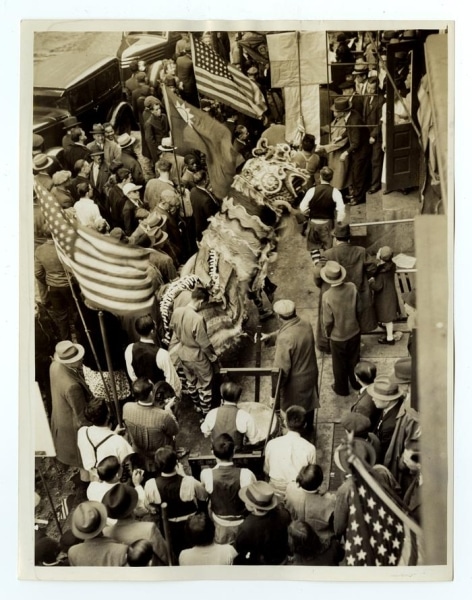

A photograph from the turn-of-the-twentieth century shows Race Street in Chinatown decorated with American flags. The crowds on the street suggest this photograph documents possibly a Fourth of July parade or patriotic event. More celebrations and parades occurred in Chinatown in 1937 in support of China. The duality and pride of both cultures is visible with the combination of a Chinese dragon and American flags.

Chinese Parade in Chinatown to Celebrate 26th Anniversary of Founding of Chinese Republic and to Raise Money for War Sufferers (Philadelphia, October 10, 1937). Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

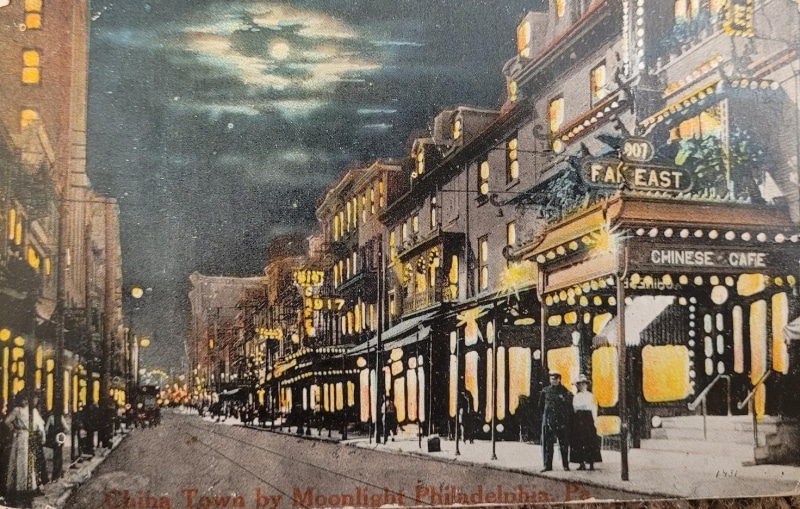

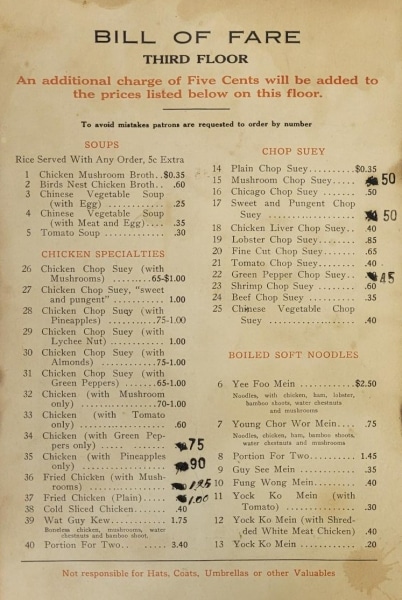

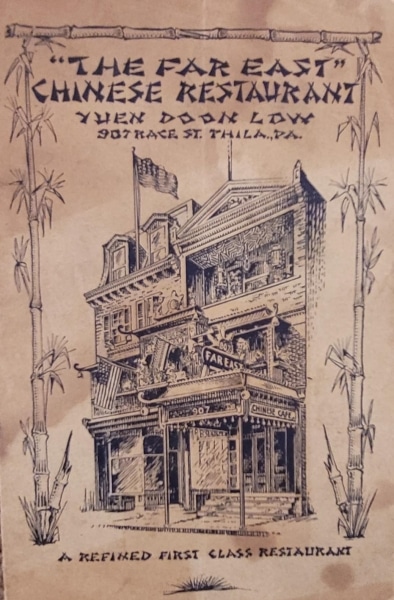

By the twentieth century, there was a proliferation of non-Asian people traveling to Chinatown desiring to encounter and try something different. Restaurants increasingly became experiential, a way for Americans to consume a new cuisine and view cultural displays. The Far East Chinese Restaurant, located at 907-909 Race Street, opened in 1908. The building featured Chinese architectural details on the awning and balcony and later had neon lights. The restaurant became an easily identifiable public landmark and tourist destination. This postcard shows a white man police officer and a white woman posed in front of the restaurant. The same photograph is used again in a colorized and altered postcard. The sky is darkened, and the moon, as well as the glow of lights from the buildings, has been added. The Far East served both Chinese and non-Chinese customers. The menu, entirely in English, shows a variety of available dishes, including the Chinese American restaurant staple, chop suey. The Far East ceased operations in 1952, but restaurants in Chinatown continue to proliferate.

Chinatown, Philadelphia, Pa. (Philadelphia, ca. 1911). Gift of Linda Kimiko August.

China Town By Moonlight, Philadelphia, Pa. (Philadelphia, ca. 1915). Gift of Linda Kimiko August.

“The Far East” Chinese Restaurant (Philadelphia, ca. 1920). Gift of Linda Kimiko August.

Aero Service Corporation, Construction of the Ridge-8th Street Subway (Philadelphia, 1931).

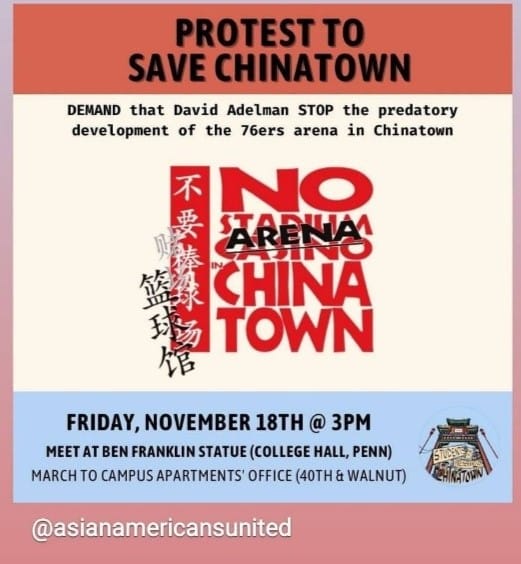

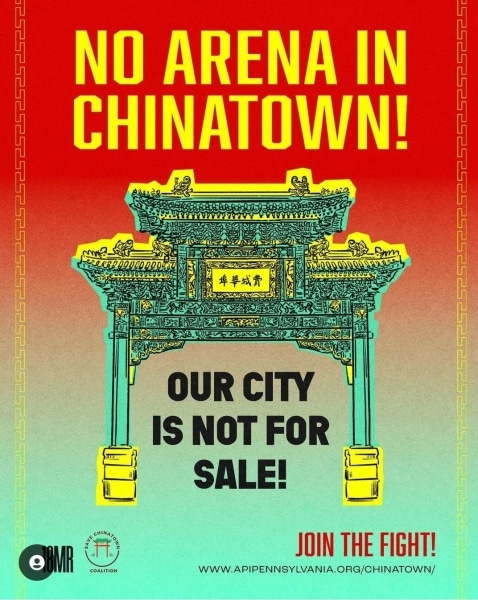

Over the past century, Chinatown has faced numerous threats from urban renewal projects. Eminent domain provided the city government a legal way for homes and businesses to be demolished for public use and a neighborhood to be gentrified. Several large works projects affected the area. This aerial view shows the destruction that the building of the Ridge-8th Street subway caused before opening in 1932. The Vine Street Expressway, constructed from 1957 to 1991, levelled more buildings and also bisected the neighborhood. Both of these transportation networks brought noise and pollution. The harm caused by the Expressway has recently been acknowledged through federal funding for the Chinatown Stitch: Reconnecting Philadelphia to Vine Street. This project explores capping a portion of the highway between Broad Street to 8th Street and Callowhill Street to Race Street to allow for parks, open space, or the creation of new buildings. U.S. Senator for Pennsylvania Bob Casey stated this would “bring Philadelphia one step closer to righting historical wrongs and connecting residents to more economic opportunities.”[8] Other large-scale developments have altered the landscape of Chinatown, including the Gallery/Market East and the Pennsylvania Convention Center. Community activists rallied and resisted the proposed construction of a federal prison in 1992, a baseball stadium in 2000, and a casino in 2008. Currently, the community is protesting another attempt to relocate a sports arena for the 76ers basketball team, adjacent to the neighborhood along the 1000 block of Market Street.

Asian Americans United (@asianamericansunited). “Protest to Save Chinatown.” Instagram, Nov. 15, 2022.

Asian Pacific Islander Political Alliance (@apipennsylvania). “No Arena in Chinatown!” Instagram, April 27, 2023.

Chinatown continues to thrive as a neighborhood filled with houses, schools, cultural institutions, and places of worship. It also serves as a cultural home for the larger Asian community creating an environment of inclusion and unity. The history of Chinatown is vulnerable to erasure. It is vital to preserve and document the stories for the heritage of future generations.

[1] North American, November 9, 1876.

[2] North American, November 9, 1876.

[3] “Claiming Their Rights,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 13, 1887. “Chinatown Raided,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 8, 1890.

[4] “Jottings About the City,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 17, 1892. “All Paid Fines: Chinamen Who Transacted Business on Sunday, Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 8, 1895.

[5] “Riot in Chinatown,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 27, 1891. “A Row in Chinatown,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 12, 1893.

[6] “Chinese Laborers Must Be Deported,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 1, 1893.

[7] “They Will All Register,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 28, 1893.

[8] “Casey, Evans, Boyle Announce $1.8 Million to Reconnect Chinatown.” Press release, February 22, 2023. https://www.casey.senate.gov/news/releases/casey-evans-boyle-announce-18-million-to-reconnect-chinatown