Grandma Toppan’s Daguerreotype

No first name is provided for Grandma Toppan. She is defined by her relationship to other people.

Robert Cornelius. Grandma Toppan (Philadelphia, ca. 1841). Sixth-plate daguerreotype.

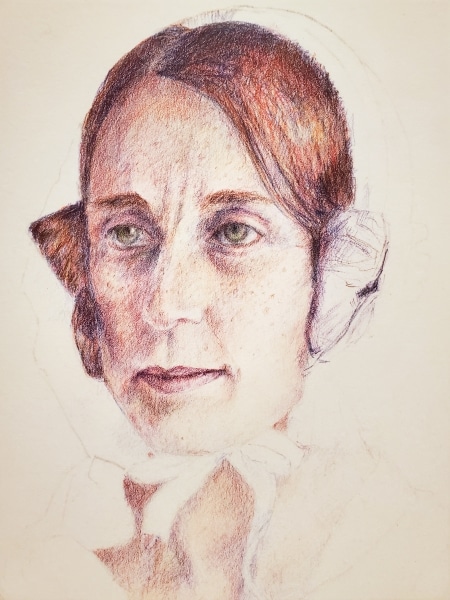

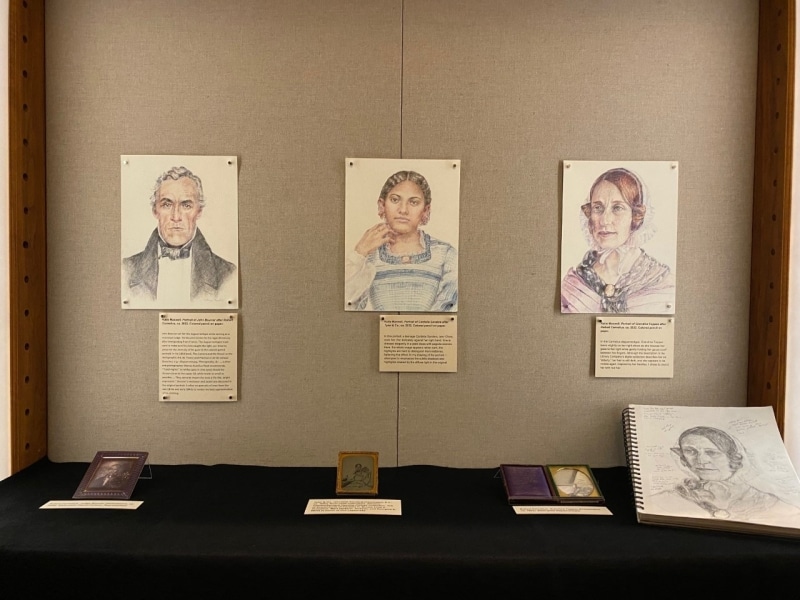

I came across her portrait in the Catching A Shadow: Daguerreotypes in Philadelphia, 1839-1860 online exhibition, and something about her grabs my attention. Spots and scratches are scattered across the surface, but the image maintains high contrast and fine details such as freckles. Her depiction will be my third colored-pencil portrait and the final piece in a series based on photographs with imperfections in the Library Company’s collection. You can find my earlier drawings here and here or view them in person at the Library Company.

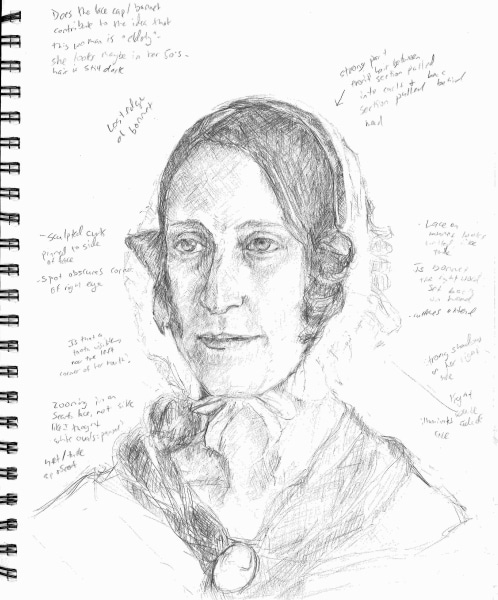

Although the description in the Library Company’s digital collection describes her as “elderly,” Toppan’s hair is still dark—she could be anywhere between 40 and 60 years old. The Library Company online exhibition, ”This Extraordinary Woman:” Portraits of Female Curiosities in Early American Print Culture explains “Women in the Victorian era were considered elderly when they entered menopause, while men were characterized as old based on their productive capabilities.”

Toppan wears a lace cap tied under her chin and an off-the-shoulder dress with a pointed bodice and voluminous sleeves.

A light source from Toppan’s left illuminates the planes of her face. She leans slightly on her right elbow as she focuses her gaze to her right, away from the light, while gently holding her gauzy scarf between her fingers.

In his 1864 book, The Camera and the Pencil, author Marcus Aurelius Root recommends in Chapter X: Hints Upon Sitting “If the subject has very light blue eyes, or light eyes of whatever shade, the face should be turned partially away from the light,…Light or blue eyes may be thus made to look dark and clear…” Although this book was written decades after this photograph was taken, both Root and pioneering daguerreotypist Robert Cornelius must have ascribed to similar compositional philosophies.

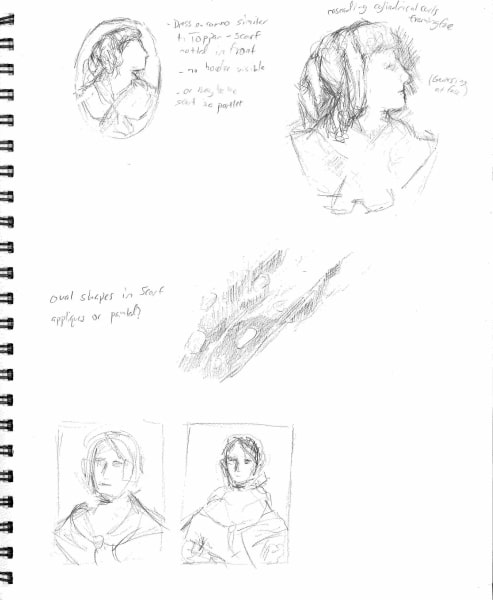

Before I add color, I need to figure out some other details.

I tackle the cameo that fastens the scarf first.

Left: Georgian Pinchback Cameo Goddess Earrings. 1stDibs.

Unlike other popular cameo jewelry styles featuring idealized classical figures, like the example above, Toppan’s cameo depicts the bust of a woman wearing what appears to be contemporary dress.

The gauzy, dark scarf with its contrasting pattern and etching reminds me of what my own stylish grandmother wore in the 1950s, something she may have had in common with Grandma Toppan.

[Women 1840, Plate 040] (United States, 1840). Metropolitan Museum of Art, Costume Institute. Gift of Woodman Thompson.

In Toppan’s 1841 portrait, her dress looks strikingly similar to those illustrated in this 1840 fashion plate. The pointed bodice resembles the woman in fuchsia, while her sleeves are very similar to the women wearing green and white. Even the cylindrical curls on either side of Toppan’s face are reminiscent of the woman in fuchsia. Toppan must have stayed up to date on the latest fashions.

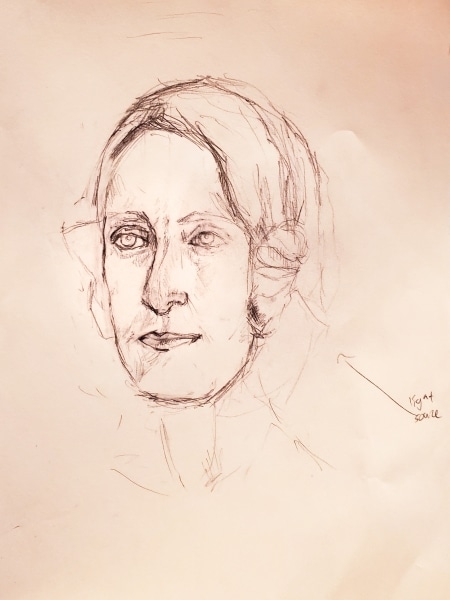

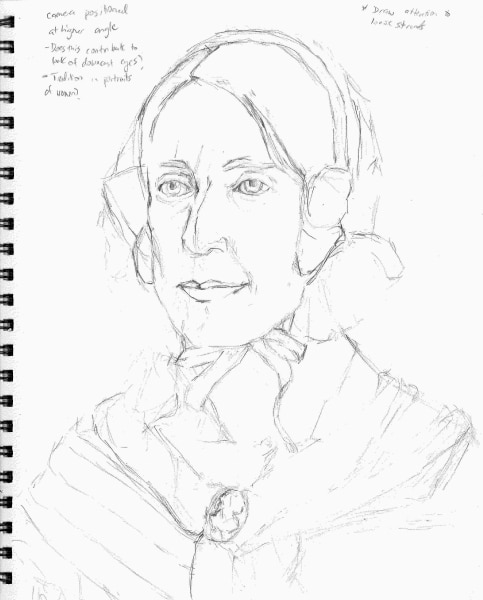

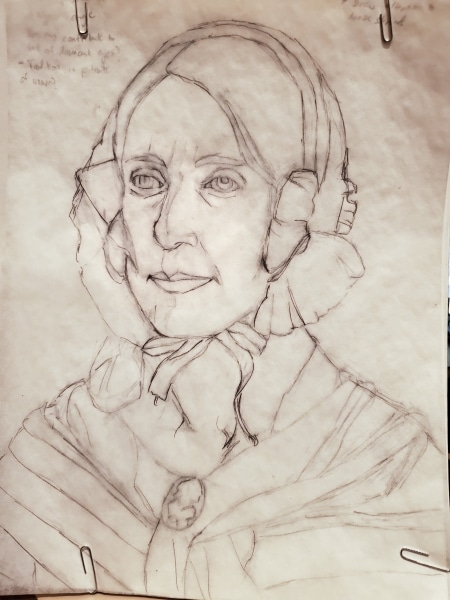

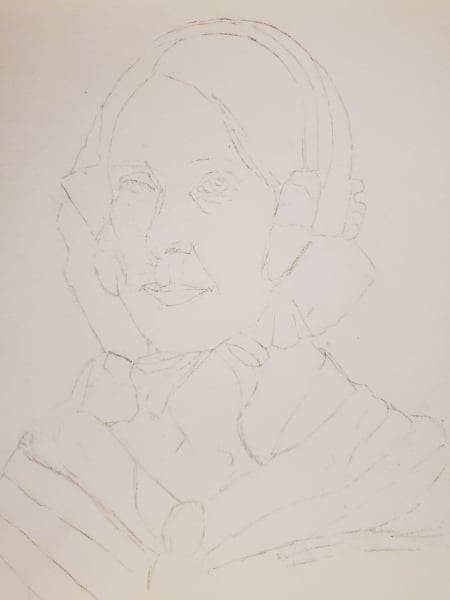

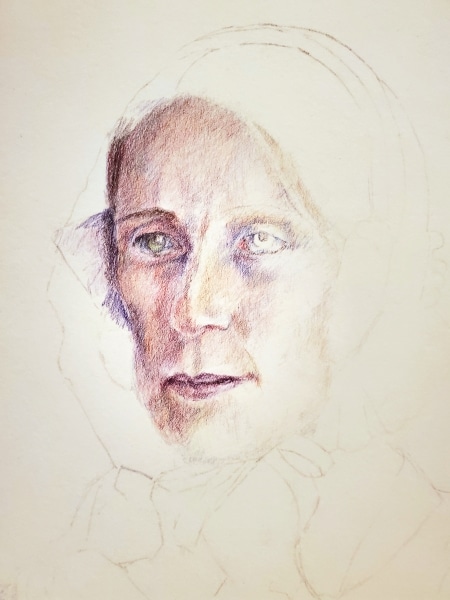

After settling on a composition that focuses on the face but still shows some details of the clothing, I draw the final sketch.

A few strands of hair appear to have come loose from Toppan’s sculpted style, adding an element of individuality.

In my first portrait attempt, I pressed too hard on the tracing paper when transferring the drawing and indented the paper. The second time I didn’t press hard enough, and the drawing was barely visible. I have now finally hit the happy medium of tracing paper transfers.

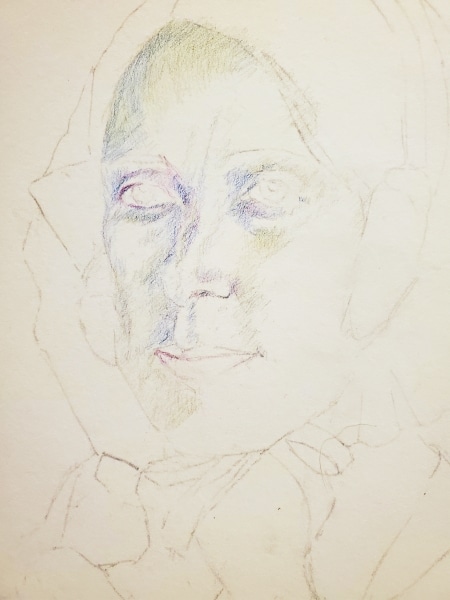

I’ve chosen to use blues and greens to give Toppan a cool-colored undertone.

Yellow ochre, magenta, and red-violet tones are applied next. Inspired by Toppan’s freckles, I depict her with red hair and green eyes.

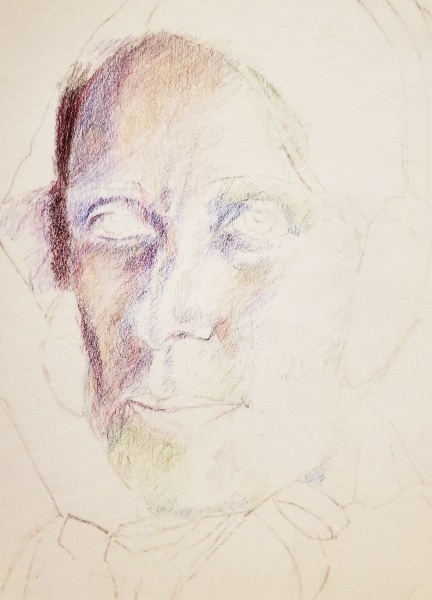

Late in the game, I realize that I’ve drawn her mouth too low and a bit small, and as a result, her chin also looks too small.

I’m able to redraw her lips in their proper location, but they end up darker than I originally intended. Erasers can only do so much.

I complete the cap using a mix of colors, including some orange where the fabric sits close to Toppan’s skin. For the colors of the clothing, I draw from both the 1840 fashion plate referenced earlier and this 1848 painting.

Maria Carolina Augusta di Borbone, Principessa delle Due Sicilie,1848. Wikimedia Commons.

A tricky part is capturing the texture of the scarf. Although the color and design in the example below are different from Toppan’s scarf, the weave of the lace and the oval-shaped appliques look similar.

Right: Lace Scarf (Belgium, 1837). Worn by Mrs. Bright Rupert Paxton (Emmeline Barton) (American). Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Adeline Edmunds.

The fabric over Toppan’s right shoulder is pulled close enough together that it appears mostly opaque. I suggest depth with a cross-hatching pattern.The fabric over Toppan’s left shoulder is more translucent, so I block in the skin tone first, then lightly cross-hatch in purple, blue, and black.

As I complete Grandma Toppan’s portrait, I wonder who she was and why our only detail about her is that she was a grandma. In the 1986 edition of the Library Company’s Annual Report, the Library Company describes purchasing Toppan’s daguerreotype:

We added a beautiful silver-plate portrait of an elderly woman by Cornelius that was accompanied by an old slip of paper inscribed with the words “Grandma Toppan.”We don’t know for sure, but we suspect (and hope) that she is related to Charles Toppan of the banknote engraving company Draper, Toppan & Co., […] And we would like to think that there is some irony and clash of technologies in that a banknote engraver took his grandmother to Robert Cornelius’ studio, the first portrait photography studio in the world.

However, I like to think that Grandma Toppan herself took the trip to Cornelius’s studio, maybe to celebrate the birth of a grandchild.

Sources:

Root, M.A., The Camera and the Pencil; or the Heliographic Art. Philadelphia: M.A. Root and J.B. Lippincott & Co.,1864.

https://archive.org/details/camerapencilorh00root/page/114/mode/2up?view=theater

Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries: Digital Collections. Costume Institute Fashion Plates: Fashion plates, 1790-1929.

Recommended Listening:

“Fashioning Family History with Photo Detective Maureen Taylor.”Dressed: The History of Fashion. Podcast audio,recorded November 29, 2022,.