Shareholder Spotlight: Sophia Borie (1789-1876)

Dana Dorman, Archivist, Library Company Papers Project

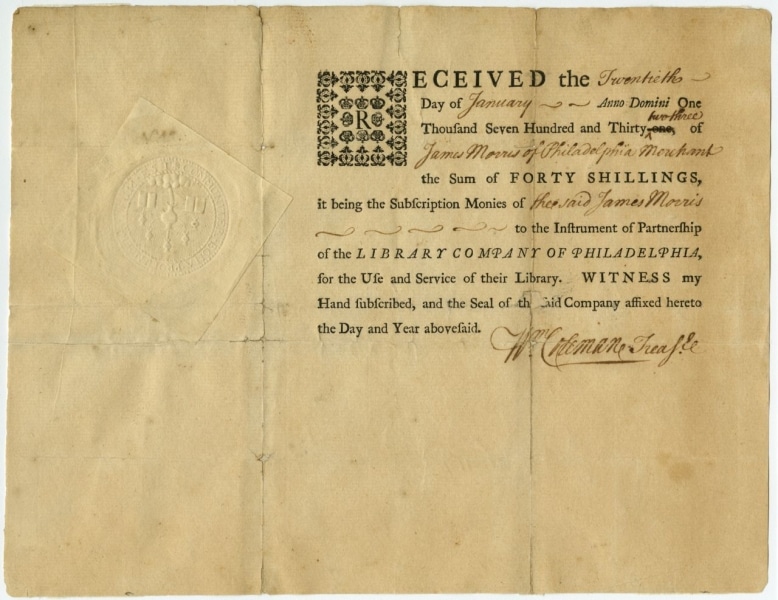

Image: Receipt for a Library Company share, 1733.

We continue our monthly “Shareholder Spotlight” series by taking a closer look at Share #1057 and its first owner, Sophia/Sophie Borie (1789-1876).

Shareholders have always been the backbone of the Library Company of Philadelphia. Starting with the first group of fifty tradesmen who formed the library in 1731, shareholders have provided crucial financial support each year for our mission to “pour forth benefits for the common good.”

We keep careful track of who has owned each historic share, and our list of 9,800+ shareholders includes signers of the Declaration and Constitution, merchants, doctors, soldiers, scientists, artists, philanthropists, politicians, and much more.

Share #1057

This share was first issued to “Sophia Borie” on May 13, 1840. Like another previously profiled shareholder, Sophia had been one of the shareholders of the Pennsylvania Library of Foreign Literature and Science, which was added to the Library Company on this date.

The Library Company’s records provide few other details about Sophia.

However, when Sophia’s share #1057 was transferred to its next owner in 1879, the transfer was managed by the executor of Sophia’s estate, Charles L. Borie (1819-1886). That fact leads me to conclude that Sophia Borie is the same person as Sophie Beauveau Borie (1789-1876), who was Charles’ mother.

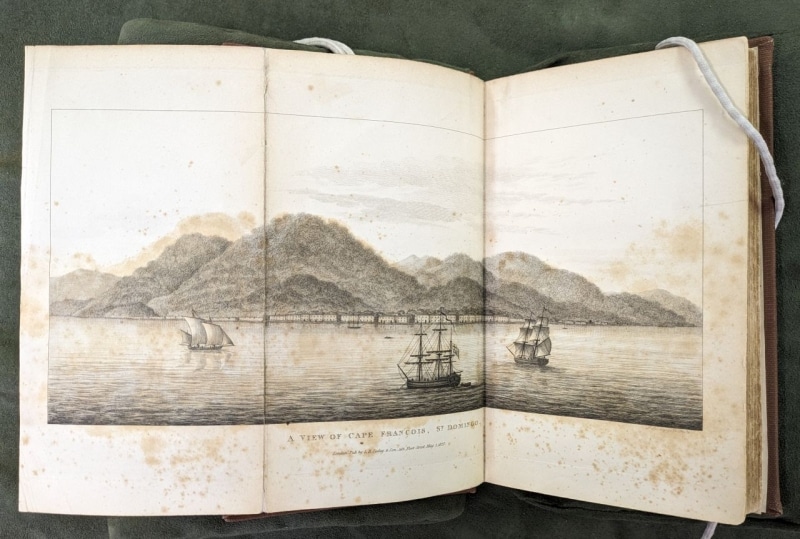

Sophie Beauveau Borie was born in Cap Français in the French colony of Saint Domingue (now Haiti) just two years before the start of the Haitian Revolution.

During most of her childhood, her family apparently alternated their time between Philadelphia and Saint Domingue because of her father’s work as a merchant. This was a momentous and violent time in the colony, as free and enslaved Blacks sought their independence and white French colonists attempted to retain control. (For example, see this depiction of the 1791 revolt of enslaved people in Cap Français, or this 1803 depiction of how French colonists used blood hounds to attack Black residents.)

Image: A View of Cape François, St. Domingo. Frontispiece from W. W. Harvey, Sketches of Hayti; from the Expulsion of the French, to the Death of Christophe (London: L. B. Seeley and Son, 1827).

Sophie’s father died in Cap Français in 1802 during a Yellow Fever epidemic. Sophie’s mother eventually brought her five daughters to Philadelphia. A family narrative claimed that they escaped on the “last vessel allowed to leave port, their property having been confiscated by the insurrectionists.”[i]

In Philadelphia, Sophie’s mother supported the family by operating a china shop and boarding house, whose lodgers included other merchant exiles from Saint Domingue. Sophie married one of those exiles in 1808: John Joseph (J. J.) Borie (1776-1834).[ii]

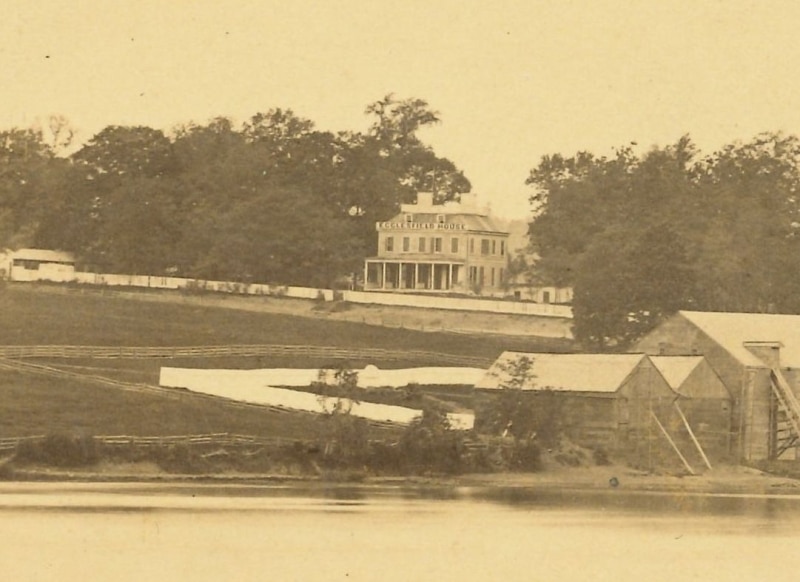

Sophie and J. J. would eventually have twelve children. They owned a city home on 4th Street and a farm known as “Eaglesfield” in what is today Fairmount Park. By the time Sophie became a Library Company shareholder in 1840, she was a widow.[iii]

Image: J. J. and Sophie Borie once owned this farm known as “Eaglesfield” in what is today Fairmount Park. Detail from [Eaglesfield House (hotel) at Girard Ave. Bridge, from East bank of Schuylkill River] [graphic] (Philadelphia, circa 1870). Albumen print.

Technically, Sophie would have had access to the Library Company’s holdings well before 1840. Her husband J. J. had acquired Library Company share #364 on March 6, 1824, and held it for the next eleven years.

Perhaps Sophie became a shareholder in the Pennsylvania Library of Foreign Literature and Science to complement the French language works she could access at the Library Company? Or perhaps after J. J.’s Library Company share was sold in 1825, she took a break from subscription libraries until sometime after the new Foreign Library was organized in 1831?

Either way, she became a named shareholder in the Library Company when the Foreign Library was added to the Library Company in 1840.

Sophie maintained her Library Company share for the rest of her life.

After her death, Sophie’s son and executor Charles L. Borie transferred share #1057 to Susan P. Halsey Borie (1835-1913), Sophie’s daughter-in-law and the wife of Charles’ brother John Joseph Borie II (1830-1882).

Charles himself had become a Library Company shareholder just a few years before. He had acquired share #901 on December 1, 1874. Charles’ son Beauveau Borie (1846-1930) was also involved with the Library Company. He acquired share #1066 on Sept. 6, 1877 for a short time, and then later owned share #1074 for more than thirty years.

Share #1057 eventually passed to Susan’s great-nephew, Beauveau Borie, Jr. (1874-1963). The share remained in the Borie family until 1965, and has been owned by four people total in its history.

Not yet a shareholder?

Share #1057 is currently available. We work hard to match potential shareholders with historic shares that match their interests, and we would love to match you with Sophia Borie’s share or another option. To learn more, reach out to our Development Office at development@librarycompany.org or 215-546-3181 ext. 142.

—–

[i] This quote comes from genealogical materials in the Borie Family Papers (Collection 1602) at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. See page 292, note 14, in Carrie L. Glenn, “The Revolutionary Atlantic of Elizabeth Beauveau and Marie Rose Poumaroux: Commerce, Vulnerability, and U.S. Connections to the French Atlantic, ca. 1780-1860” (PhD diss., University of Delaware, 2020). Glenn was a Library Company 2017-2018 Program in Early American Economy and Society Dissertation Fellow, as well as a 2020-2021 Program in Early American Economy and Society Postdoctoral Fellow.

[ii] Sophie’s husband, J. J. Borie, had first married a mixed-race woman in Saint Domingue named Marie Rose Poumaroux. After he was living in Philadelphia, J. J. argued that their marriage was invalid, and he married Sophie Beauveau. Decades later, descendants of J. J.’s daughter with Poumaroux filed a lawsuit claiming that they should have received a portion of his large estate. For much more about Sophie’s mother and J. J. Borie’s first wife, and their respective experiences as white and mixed-race women in the French Atlantic world, see Glenn, “The Revolutionary Atlantic of Elizabeth Beauveau and Marie Rose Poumaroux: Commerce, Vulnerability, and U.S. Connections to the French Atlantic, ca. 1780-1860.”

[iii] For an overview of the Borie family, see the finding aid for the Borie Family Papers (Collection 1602), Historical Society of Pennsylvania.